A Comprehensive Note on the History of English Drama

The history of English drama is a rich and fascinating journey that spans over a millennium, evolving from religious rituals and morality tales into a diverse and complex form of artistic expression that continues to thrive in the modern era. Its development can be studied through distinct historical periods, each offering unique contributions in terms of style, themes, language, and structure. These periods reflect the shifting cultural, social, religious, and political landscapes of England, and the drama produced in each era serves as both a mirror and a critique of the times in which it was created.

The Medieval Period (500–1500)

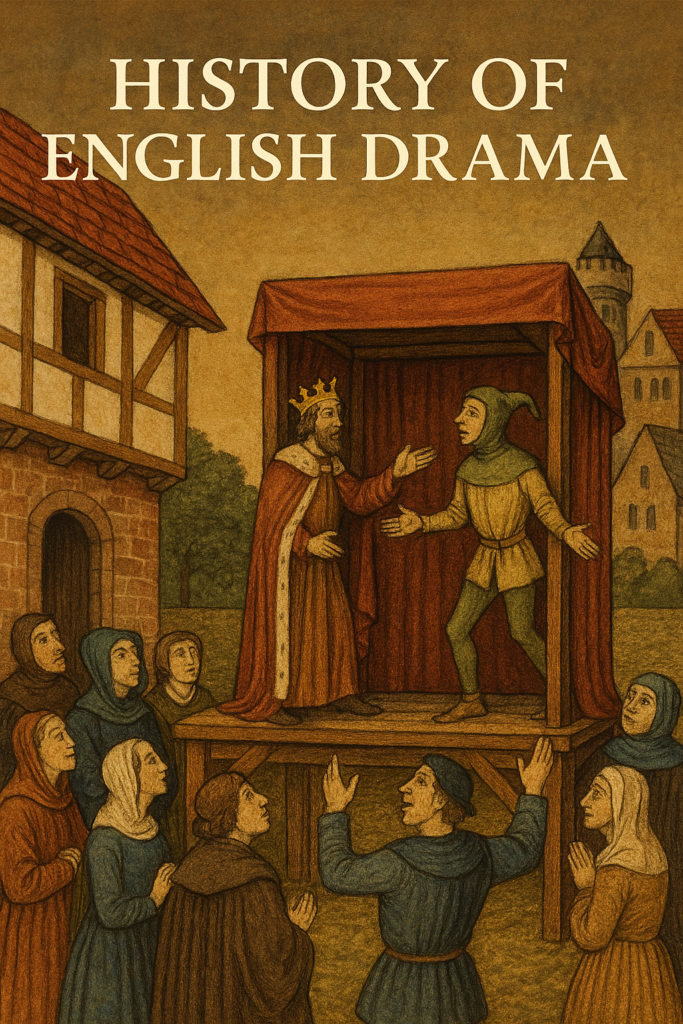

English drama began during the early Middle Ages, largely as a means of religious instruction. In an age when most people were illiterate, the Church used dramatic performances to communicate Biblical stories and moral lessons to the general populace. The earliest forms of drama were liturgical plays, performed in Latin by priests and choirboys inside the church as part of religious ceremonies. These plays depicted scenes such as the Nativity, the Passion of Christ, and the Resurrection. As their popularity grew, these plays began to move outside the church and were translated into vernacular English. They evolved into more elaborate productions known as Mystery plays and Miracle plays. Mystery plays dramatized stories from the Bible, from the Creation to the Last Judgment, while Miracle plays recounted the lives and miracles of saints. These plays were often performed during religious festivals, particularly the Feast of Corpus Christi. They were organized into cycles and performed by trade guilds on pageant wagons that moved from street to street. Famous cycles include the York Cycle, the Chester Cycle, the Wakefield Cycle, and the Coventry Cycle. These performances were communal events, involving large numbers of townspeople and attracting massive audiences. In the later medieval period, Morality plays emerged as a new form of drama. Unlike the earlier religious plays, Morality plays were allegorical and featured personified virtues and vices, such as Good Deeds, Knowledge, Pride, and Gluttony. The most famous example is Everyman, which portrays the journey of a man summoned by Death and his reckoning with spiritual salvation. These plays emphasized moral lessons and the eternal battle between good and evil. Toward the end of the medieval period, Interludes also became popular. These were short, humorous pieces often performed at noble households and royal courts, and they paved the way for the secular and humanistic concerns of Renaissance drama.

The Renaissance and Elizabethan Period (1500–1660)

The Renaissance brought a profound transformation to English drama. Influenced by classical antiquity and humanism, playwrights began to explore secular themes, complex characters, and intricate plots. Drama shifted from religious instruction to entertainment and intellectual engagement. The first English comedy, Ralph Roister Doister by Nicholas Udall, and the first English tragedy, Gorboduc by Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton, mark the beginning of this transformation. The University Wits, a group of educated playwrights including Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, Robert Greene, and John Lyly, laid the foundation for the golden age of Elizabethan drama. Marlowe introduced blank verse and heroic tragedy with works like Tamburlaine and Doctor Faustus. Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy established the revenge tragedy genre. These writers expanded the dramatic scope and language of the time. William Shakespeare emerged as the most significant figure of this period, writing over thirty plays that encompassed tragedy (Hamlet, Macbeth, Othello, King Lear), comedy (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Twelfth Night, As You Like It), and history (Henry IV, Richard III). Shakespeare’s genius lay in his deep psychological insight, poetic brilliance, and ability to explore universal human experiences. His plays appealed to all levels of society and transformed the English stage. Public theatres such as The Globe, The Rose, and The Swan became central to cultural life. The Elizabethan stage was open and bare, relying on language and imagination rather than elaborate scenery. The audience was diverse, ranging from nobles to commoners, and performances were vibrant communal experiences. After the death of Elizabeth I, the Jacobean (1603–1625) and Caroline (1625–1649) periods followed. Playwrights such as Ben Jonson, John Webster, Francis Beaumont, and John Fletcher continued to produce significant works. Jonson was known for his satirical comedies like Volpone and The Alchemist, while Webster’s tragedies The Duchess of Malfi and The White Devil explored themes of corruption and revenge with grim intensity. The theatre became darker and more cynical, reflecting the political and social anxieties of the time. Tragicomedies, blending serious and comic elements, gained popularity. However, the rising Puritan influence and political instability would soon bring this flourishing period to an end.

The Puritan Interregnum (1642–1660)

In 1642, with the outbreak of the English Civil War and the rise of the Puritan government under Oliver Cromwell, all public theatres were closed. The Puritans regarded theatre as immoral and a threat to social order. Dramatic performances were banned, and actors were persecuted. This period represents a significant hiatus in the history of English drama. However, drama did not disappear entirely. Some writers turned to closet dramas—plays meant to be read privately rather than performed. These works allowed authors to explore political and philosophical themes in a censored environment. Though the theatrical tradition suffered, the literary form of drama endured in private circles, awaiting its revival with the return of the monarchy.

The Restoration Period (1660–1700)

With the restoration of Charles II in 1660, the English theatre experienced a dramatic revival. Charles had spent years in exile at the French court and brought with him a taste for continental drama. Theatres reopened, and drama flourished once more, particularly in the form of Restoration Comedy. These comedies were characterized by their wit, sexual innuendo, and satirical portrayal of upper-class manners and relationships. Stock characters such as the fop, the rake, the coquette, and the country squire populated these plays. Notable playwrights include William Wycherley (The Country Wife), William Congreve (The Way of the World), and George Etherege (The Man of Mode). These plays were often performed in newly constructed indoor theatres, such as the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane, which featured advanced stage machinery and scenic design. For the first time, women were allowed to perform on stage, and female playwrights like Aphra Behn gained recognition. Behn’s The Rover is notable for its bold themes and female perspective, making her one of the first professional female writers in English literature. While Restoration Comedy thrived, tragedy struggled to regain its former glory. Heroic tragedies in rhymed couplets attempted to capture grandeur but often lacked emotional depth. Despite this, John Dryden’s All for Love, a reworking of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, remains a significant work from the period.

The 18th Century (1700–1800)

The 18th century saw a shift away from the licentiousness of Restoration drama toward more moralistic and sentimental themes. Sentimental Comedy emerged as the dominant form, focusing on virtuous characters, emotional appeal, and moral lessons. These plays aimed to inspire tears and elevate the audience’s sense of morality. Richard Steele’s The Conscious Lovers is a prime example. However, not all dramatists embraced sentimentality. Oliver Goldsmith and Richard Brinsley Sheridan revived the comedy of manners with a new sophistication. Goldsmith’s She Stoops to Conquer and Sheridan’s The School for Scandal combined humor, wit, and social commentary, reintroducing robust comedy to the stage. Tragedy in this period often centered on domestic concerns and middle-class values. George Lillo’s The London Merchant focused on everyday people and the consequences of moral failure. The ballad opera, pioneered by John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, mixed popular tunes with political satire, influencing both musical theatre and later drama. The “well-made play” structure began to take shape, emphasizing tight plotting and clear resolutions. Though the century was less innovative than the Renaissance, it laid the groundwork for future developments in dramatic form and character.

The 19th Century (1800–1900)

The 19th century was a time of great social change, and English drama reflected the tastes and concerns of a growing middle class. Melodrama became the dominant theatrical form, characterized by exaggerated emotions, sensational plots, and clear moral distinctions. These plays featured heroes, villains, and damsels in distress, often involving dramatic rescues and spectacular effects. Melodrama catered to popular tastes and was a staple of commercial theatre. Farce and romantic comedy also found favor with audiences seeking light entertainment. Though melodrama dominated, efforts to elevate dramatic literature continued. Poets like Lord Byron and Percy Shelley experimented with verse drama, though their plays were more literary than performative. The influence of realism and naturalism began to emerge toward the end of the century. Influenced by European playwrights like Ibsen and Zola, British dramatists began to explore social issues with greater psychological depth. The Independent Theatre Movement, inspired by the Théâtre Libre in Paris, promoted serious drama and introduced audiences to continental works. While not as groundbreaking as other periods, the 19th century expanded theatre’s reach and set the stage for the dramatic revolutions of the 20th century.

The 20th Century

The 20th century witnessed a dramatic transformation in English drama, both in content and form. Early in the century, realism and social critique dominated. George Bernard Shaw emerged as a towering figure with plays like Pygmalion, Major Barbara, and Man and Superman. Shaw combined intellectual rigor with social reform, challenging class structures, gender roles, and religious hypocrisy. T.S. Eliot reintroduced poetic drama with works like Murder in the Cathedral, exploring spiritual themes in a modernist framework. Noël Coward’s witty comedies like Private Lives and Blithe Spirit offered sophisticated entertainment, while Terence Rattigan’s restrained dramas examined emotional repression and middle-class life. The post-war years brought a surge of innovation. Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot epitomized the Theatre of the Absurd, rejecting conventional plot and language to explore existential themes. Harold Pinter developed a unique style marked by ambiguous dialogue, silences, and psychological tension in plays such as The Birthday Party and The Caretaker. The 1950s saw the rise of the Angry Young Men, a group of playwrights who expressed working-class frustration and social disillusionment. John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger marked a turning point with its raw emotional power and critique of class privilege. Later decades brought increasing diversity and experimentation. Caryl Churchill’s feminist and postmodern plays, such as Top Girls and Cloud Nine, challenged traditional narratives and gender norms. Tom Stoppard combined intellectual inquiry with theatrical innovation in works like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Sarah Kane, Mark Ravenhill, and the in-yer-face theatre movement pushed the boundaries of taste and subject matter, portraying graphic violence and emotional extremity. Documentary and verbatim theatre gained prominence with plays like David Hare’s Stuff Happens and Alecky Blythe’s London Road, using real events and testimonies to explore political and social issues. Companies like Complicite and Punchdrunk redefined performance with multimedia, movement, and immersive techniques.

The 21st Century and Beyond

Contemporary English drama is characterized by plurality and innovation. Playwrights from diverse backgrounds explore themes of identity, migration, gender, climate change, and digital life. Theatres continue to evolve, incorporating technology and new media. Traditional spaces coexist with site-specific and immersive performances. New writing is encouraged by institutions such as the Royal Court Theatre, the National Theatre, and fringe festivals like Edinburgh. English drama remains a vibrant and vital part of cultural life, reflecting the complexities of a rapidly changing world.