Introduction

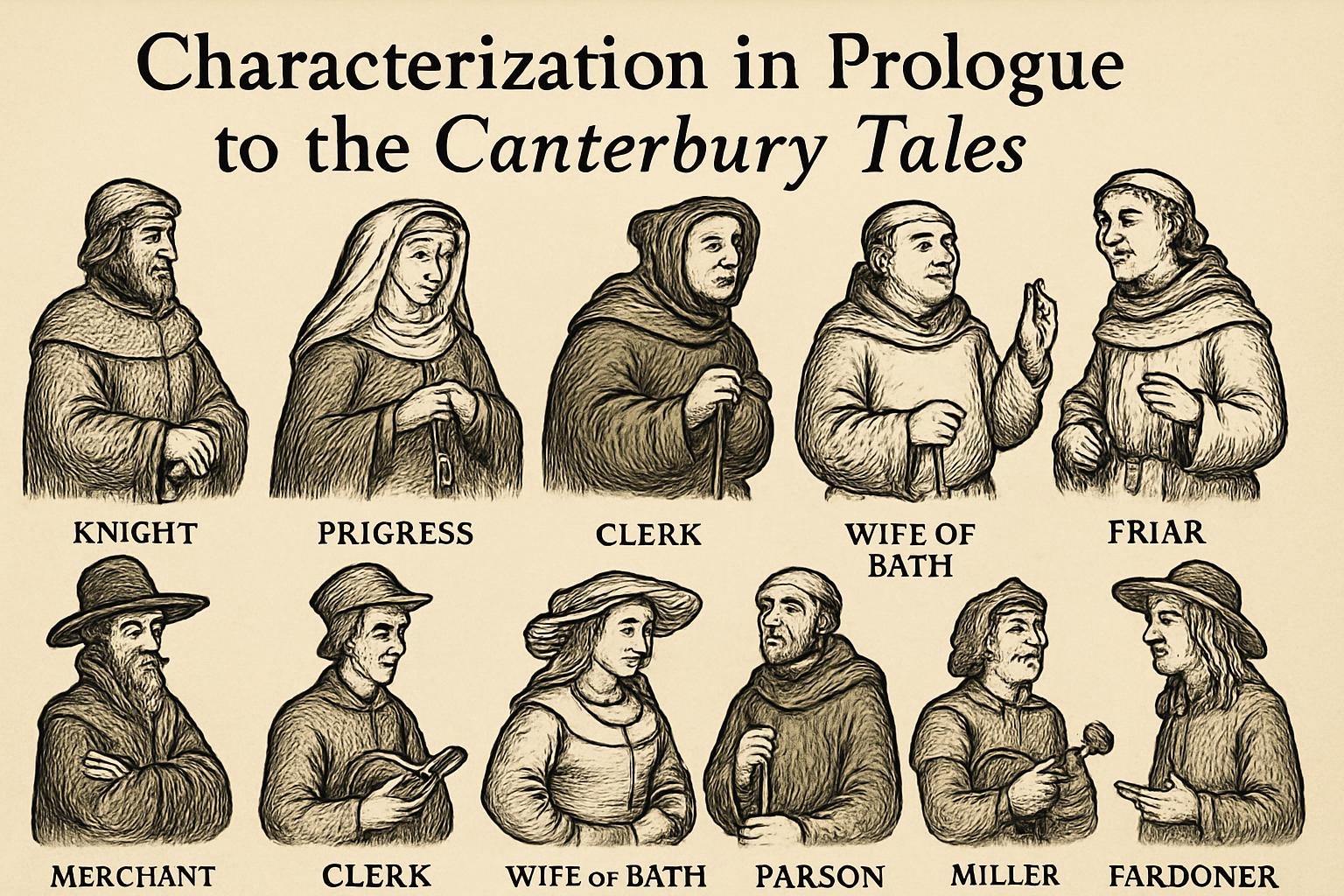

The Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales reveals Chaucer’s unmatched ability to portray human variety. Each pilgrim represents a distinct moral and social identity. Moreover, Chaucer captures manner, speech, and psychology with precise artistry. Through observation and irony, he gives life to faith, greed, and virtue. Therefore, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales unites realism with moral reflection. Every detail builds moral truth within humor and humanity. Furthermore, Chaucer’s portraits become moral mirrors of fourteenth-century England. At the same time, his sympathy tempers satire, preserving dignity within imperfection. Because of this balance, his characters appear timeless and authentic. Each description conveys both individuality and universal emotion. Ultimately, Chaucer’s characterization transforms moral instruction into art. Through language and tone, he shapes personality, revealing truth within comedy and depth within surface charm.

1. The Knight’s Nobility

The Knight embodies chivalric perfection through humility and service. Chaucer praises him as brave, loyal, and courteous. Moreover, his modesty defines moral excellence. He fights for faith, not vanity. Therefore, his character begins the moral scale of the Prologue. His clothing and demeanor reflect quiet virtue. Furthermore, Chaucer uses plain style to emphasize sincerity. The Knight’s valor harmonizes action and conscience. At the same time, his gentleness contrasts worldly pride. Because Chaucer opens with him, order and dignity dominate tone. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales establishes ideal virtue. His humanity softens heroism, showing nobility grounded in grace. Ultimately, the Knight stands as moral foundation of the pilgrimage, symbolizing harmony between courage, humility, and divine faith.

2. The Squire’s Youth

The Squire mirrors youthful charm and romantic enthusiasm. Chaucer portrays him as vibrant and graceful. Moreover, his talents extend to music, poetry, and war. His appearance reflects vitality and pride. Therefore, his character contrasts his father’s restraint. His love for beauty and pleasure defines youth’s impulsive nature. Furthermore, Chaucer balances admiration with humor. The Squire’s energy reveals courtly culture’s elegance. At the same time, vanity clouds moral depth. Because of his charm, Chaucer softens criticism through affection. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales explores generational change. His character celebrates joy yet warns against excess. Ultimately, the Squire’s blend of artistry and ambition highlights tension between idealism and maturity, reflecting youthful desire for glory and love.

3. The Yeoman’s Duty

The Yeoman symbolizes loyalty through practical service. His attire shows discipline and readiness. Moreover, Chaucer details his weapons and dress with precision. His green clothing recalls the forest’s moral strength. Therefore, the Yeoman represents middle virtue between pride and idleness. His craft defines honest labor. Furthermore, his quiet efficiency balances the Squire’s display. At the same time, his description honors working-class integrity. Because Chaucer values order and effort, the Yeoman earns admiration. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales portrays social harmony. His bow, arrows, and skill reveal constancy and devotion. Ultimately, the Yeoman reflects strength through silence, embodying virtue expressed in action rather than words.

4. The Prioress’s Grace

The Prioress reveals beauty and contradiction within devotion. Chaucer paints her as refined yet worldly. Moreover, her manners reflect aristocratic influence. Her tenderness toward animals expresses sensitivity. Therefore, her character blends faith and vanity. Her French accent and jewelry imply social desire. Furthermore, Chaucer uses gentle irony to expose pretension. Her compassion softens judgment, preserving sympathy. At the same time, her sentimentality reveals emotional shallowness. Because of this mixture, the Prioress becomes morally complex. Through her, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales explores hypocrisy and innocence. Her humanity outweighs satire, showing moral imperfection within charm. Ultimately, she represents conflict between spirituality and social ambition, embodying moral struggle behind polished grace.

5. The Monk’s Materialism

The Monk defies religious tradition with worldliness. Chaucer describes him as bold, wealthy, and independent. Moreover, his attire and habits reflect luxury. He rejects old monastic rules. Therefore, he symbolizes corruption within the church. His love for hunting replaces prayerful discipline. Furthermore, Chaucer’s tone mixes irony and amusement. His appetite for pleasure exposes moral decline. At the same time, he remains likable through confidence and energy. Because Chaucer avoids harsh judgment, his portrait feels humane. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales contrasts faith’s ideals with worldly temptation. Ultimately, the Monk’s vitality reveals how moral laxity thrives beneath charm, exposing decay behind clerical dignity.

6. The Friar’s Corruption

The Friar illustrates moral decay through charm. Chaucer shows him as persuasive and cunning. Moreover, he trades confession for gifts. His kindness hides greed. Therefore, his profession becomes business rather than service. His smooth talk wins admiration from simple people. Furthermore, Chaucer’s irony turns laughter into critique. His worldliness exposes hypocrisy within sacred duty. At the same time, his jovial tone masks moral emptiness. Because of his manipulation, charity becomes deception. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales unites humor and exposure. Ultimately, the Friar reflects corruption’s elegance. His cheerful deceit mirrors human weakness behind institutional power, revealing faith distorted by ambition.

7. The Merchant’s Pride

The Merchant displays confidence and secrecy. Chaucer depicts him as skilled yet debt-ridden. Moreover, his appearance commands respect. His beard and dress show prosperity. Therefore, his character reveals illusion of wealth. His words sound wise and deliberate. Furthermore, Chaucer’s irony turns dignity into disguise. The Merchant’s financial instability contrasts his public authority. At the same time, his secrecy deepens realism. Because Chaucer exposes pretense gently, judgment feels natural. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales reflects economic vanity. Ultimately, the Merchant embodies society’s fascination with wealth, symbolizing appearance without substance and wisdom without peace.

8. The Clerk’s Wisdom

The Clerk represents intellectual devotion and moral purity. Chaucer admires his learning and humility. Moreover, his poverty reveals spiritual strength. He values knowledge over wealth. Therefore, his character restores balance among corrupt pilgrims. His quiet dignity enriches moral tone. Furthermore, his devotion to study reflects timeless truth. The Clerk’s words teach generosity of spirit. At the same time, his simplicity exposes moral superiority. Because Chaucer honors intellect, the Clerk becomes example of inner faith. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales celebrates learning’s virtue. Ultimately, he represents wisdom unspoiled by pride, symbolizing purity preserved through thought and restraint.

9. The Sergeant at Law’s Authority

The Sergeant at Law displays prestige and control. Chaucer presents him as respected yet self-serving. Moreover, his learning brings wealth and fame. His words carry authority and caution. Therefore, his knowledge hides vanity. His attire marks his high status. Furthermore, Chaucer uses subtle irony to reveal ambition. His outward respectability conceals self-promotion. At the same time, his success contrasts spiritual emptiness. Because Chaucer values moderation, the Sergeant symbolizes moral imbalance. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales criticizes false virtue. Ultimately, he represents the conflict between justice and greed, exposing intellect without humility.

10. The Franklin’s Generosity

The Franklin represents social virtue through hospitality. Chaucer praises his kindness and wealth. Moreover, his joy in food and company symbolizes generosity. His open table reflects moral abundance. Therefore, his character embodies secular goodness. His cheerfulness contrasts clerical hypocrisy. Furthermore, Chaucer portrays pleasure as moral warmth. The Franklin’s laughter reveals purity in moderation. At the same time, luxury hints at moral risk. Because Chaucer’s tone remains balanced, admiration outweighs critique. Through him, Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales praises civic virtue. Ultimately, the Franklin stands as image of contentment, showing happiness rooted in kindness and social harmony.

11. The Merchant’s Character

The Merchant appears respectable, skilled in business, and socially confident. However, Chaucer subtly reveals irony behind his public image. Moreover, he hides personal debts beneath his proud appearance. His talk about profits and trade reveals his cunning intellect. Yet, Chaucer’s characterization exposes human vanity beneath economic success. The Merchant’s practicality contrasts with moral uncertainty. Through sharp observation, Chaucer captures hypocrisy within social ambition. Furthermore, his polished manners veil his inner frustration. Therefore, the characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales highlights financial pride and personal struggle. Chaucer’s art makes him vivid, realistic, and symbolically critical.

12. The Clerk’s Character

The Clerk from Oxford embodies intellectual purity and humble wisdom. He owns few possessions yet treasures books above all else. Moreover, his devotion to study outweighs worldly ambition. Chaucer portrays him as sincere, moral, and spiritually deep. His speech, though measured, reveals clarity and idealism. Therefore, his characterization reflects medieval respect for learning. The Clerk’s poverty contrasts his moral richness, symbolizing true virtue. Furthermore, Chaucer’s detail elevates knowledge as sacred pursuit. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales celebrates him as voice of intellect and conscience. Ultimately, his simplicity and thoughtfulness illuminate the poem’s moral design.

13. The Sergeant at Law’s Character

The Sergeant at Law stands as an image of authority and skill. Chaucer describes him as learned and respected within legal circles. Moreover, he seems perfect in his profession, knowing every case and law. Yet, irony undercuts his perfection, exposing subtle self-praise. His fame hides vanity behind formal speech and wisdom. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization questions social reputation and human pride. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales portrays him as shrewd yet superficial. Furthermore, his precision masks ambition rather than justice. Through humor and irony, Chaucer balances respect and critique. Thus, the character embodies legal mastery and concealed moral weakness.

14. The Franklin’s Character

The Franklin symbolizes wealth, hospitality, and cheerful simplicity. Chaucer presents him as a generous landowner who loves pleasure. Moreover, he values fine food, wine, and sociable living. His lifestyle represents comfort yet hints at moral shallowness. The Franklin’s joy in material success contrasts with spiritual moderation. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization blends admiration with moral commentary. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses him to represent rural nobility. Furthermore, his indulgence exposes human desire for pleasure and reputation. Through vivid imagery, Chaucer reveals the charm of worldly happiness. Ultimately, the Franklin’s portrait joins humor, realism, and moral reflection.

15. The Haberdasher and Guildsmen

The Guildsmen—Haberdasher, Carpenter, Weaver, Dyer, and Tapestry Maker—represent rising middle-class pride. Chaucer describes them as prosperous and socially ambitious. Moreover, their polished gear reflects self-importance and vanity. Their wives’ aspirations strengthen their class-conscious behavior. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales explores ambition and social mobility. He praises their work ethic while exposing pretentious manners. Furthermore, their uniformity symbolizes collective identity rather than individuality. Through gentle satire, Chaucer reveals early capitalism’s vanity and discipline. The Guildsmen embody progress, pride, and the struggle for recognition. Thus, Chaucer combines realism with humor and moral perception.

16. The Cook’s Character

The Cook appears skilled yet morally flawed. Chaucer praises his culinary expertise but also mocks his physical defect. Moreover, his ulcer becomes a symbol of hidden corruption. The Cook’s mixture of talent and vice deepens realism. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization blends humor with moral satire. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses him to expose human imperfection. Furthermore, his presence reflects irony between profession and purity. Despite his art, moral decay mars his charm. Chaucer’s detailed portrait joins comedy with critique. Ultimately, the Cook embodies humanity’s dual nature—skilled yet morally stained.

17. The Shipman’s Character

The Shipman embodies strength, independence, and moral ambiguity. He sails fearlessly across dangerous seas and defends his trade. Moreover, he uses cunning tactics to ensure profit and survival. Chaucer admires his courage yet notes his ruthless side. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales presents a vivid contrast between freedom and vice. The Shipman’s practicality overshadows ethical restraint. Furthermore, his harsh justice reflects sea law over moral law. Chaucer’s realistic detail highlights human adaptability and moral complexity. Thus, the Shipman becomes a portrait of worldly endurance, ambition, and danger.

18. The Physician’s Character

The Physician combines medical skill with material ambition. Chaucer praises his science yet exposes greed beneath his virtue. Moreover, his devotion to gold outweighs care for healing. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales illustrates human conflict between intellect and morality. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization reveals intellect corrupted by avarice. Furthermore, his astrology-based treatment reflects medieval superstition. Chaucer’s irony deepens the satire, showing wisdom tainted by desire. The Physician’s knowledge commands respect yet invites moral suspicion. Ultimately, he stands as symbol of brilliance enslaved by greed. Chaucer’s insight merges realism with moral reflection.

19. The Wife of Bath’s Character

The Wife of Bath is bold, confident, and experienced. She embodies female authority and worldly wisdom. Moreover, her rich attire and gap-toothed smile reflect sensual vitality. Chaucer gives her voice unmatched individuality and humor. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales celebrates female self-expression through her vivid personality. Furthermore, her marriages symbolize mastery of love and social independence. Chaucer’s characterization balances satire and admiration. She challenges patriarchal control through her wit and storytelling. Ultimately, the Wife of Bath stands as one of literature’s most dynamic women. Her character merges realism, humor, and feminist strength.

20. The Parson’s Character

The Parson embodies pure devotion and moral integrity. Unlike corrupt clerics, he lives humbly and preaches through example. Moreover, he practices what he teaches, showing spiritual consistency. The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales presents him as the ideal priest. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization contrasts true faith with hypocrisy. Furthermore, his compassion for sinners expresses Christian virtue. Through him, Chaucer illustrates sincerity within a corrupted Church. The Parson’s simplicity radiates dignity and moral strength. Ultimately, he stands as moral compass among pilgrims. Chaucer’s art captures holiness without exaggeration, blending realism with spiritual perfection.

21. The Plowman’s Character

The Plowman, brother of the Parson, represents pure Christian labor and humility. He works honestly, helping others without selfish intent. Moreover, he practices faith through simple action, not empty words. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales celebrates genuine goodness over wealth or status. The Plowman’s simplicity contrasts moral corruption among higher ranks. Furthermore, his service to others reveals spiritual nobility beyond class limits. Chaucer presents him as a symbol of honest toil and moral endurance. Ultimately, the Plowman reflects the poem’s moral vision—virtue through action and sincere devotion.

22. The Miller’s Character

The Miller stands as rough, bold, and humorous. Chaucer portrays him as strong yet coarse in manner and speech. Moreover, he cheats customers by manipulating grain scales. His red beard and wart symbolize lust and deceit. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses him for comic realism and moral satire. Furthermore, his loud personality exposes the lower class’s vitality and vice. Chaucer’s description mixes laughter with moral warning. The Miller’s vulgarity entertains yet critiques greed and pride. Ultimately, his portrait reveals how humor can expose moral disorder and social truth.

23. The Manciple’s Character

The Manciple represents cleverness and financial wit. Chaucer presents him as shrewd despite his lack of education. Moreover, he outsmarts learned men through sharp management. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales highlights intelligence shaped by experience. His character reveals irony between knowledge and worldly success. Furthermore, his practicality reflects wisdom gained through trade, not scholarship. Chaucer’s humor celebrates wit while exposing cunning manipulation. The Manciple’s craftiness shows intellect as tool for survival. Ultimately, he embodies common sense, social mobility, and human adaptability. Chaucer’s art transforms ordinary men into moral reflections.

24. The Reeve’s Character

The Reeve appears thin, irritable, and calculating. Chaucer depicts him as skilled manager and silent observer. Moreover, he manipulates finances to serve his own interest. His deceit hides behind perfect recordkeeping. Therefore, Chaucer’s characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales exposes hypocrisy within authority. Furthermore, the Reeve’s cold intelligence contrasts the Miller’s crude energy. Chaucer reveals greed’s subtle form through efficiency and silence. The Reeve’s control symbolizes power through intellect and fear. Ultimately, his portrayal merges realism and satire, showing moral decay behind order. His precision masks corruption under disciplined appearance.

25. The Summoner’s Character

The Summoner is grotesque, corrupt, and morally blind. Chaucer paints his face with boils and sores as symbols of inner vice. Moreover, his misuse of Church authority exposes deep hypocrisy. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales criticizes ecclesiastical corruption through him. Furthermore, his drunkenness and lust mock sacred duty. He knows a few Latin phrases, using them for deceit. Chaucer’s dark humor exposes religious exploitation for personal gain. The Summoner’s character reveals the moral collapse of clerical figures. Ultimately, his portrait unites satire, realism, and sharp moral condemnation.

26. The Pardoner’s Character

The Pardoner embodies deception disguised as piety. Chaucer presents him as smooth-tongued, cunning, and morally hollow. Moreover, he sells false relics to exploit faith for money. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales critiques greed within spiritual roles. Furthermore, his eloquence reveals manipulation through sacred language. Chaucer’s irony exposes performance over sincerity. The Pardoner’s moral emptiness contrasts his persuasive charm. His voice preaches virtue while practicing deceit. Ultimately, his characterization reflects corruption as both social and spiritual disease. Chaucer’s artistry transforms hypocrisy into a powerful moral warning.

27. The Host’s Character

The Host, Harry Bailey, symbolizes unity, leadership, and practical wisdom. Chaucer describes him as cheerful and decisive. Moreover, he organizes the storytelling contest with fairness and humor. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses him to frame structure and tone. Furthermore, his humor balances tension among diverse pilgrims. His personality brings realism through lively dialogue and judgment. Chaucer’s characterization makes him mediator between class, faith, and wit. The Host embodies community spirit and narrative order. Ultimately, he becomes both guide and participant, linking humanity through shared storytelling.

28. The Narrator’s Character

The Narrator represents observation, humility, and irony. Chaucer shapes him as seemingly naïve yet deeply perceptive. Moreover, he records each pilgrim’s traits with humor and fairness. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales gains unity through his reflective voice. Furthermore, his mild tone softens criticism while deepening insight. Chaucer uses him to balance sympathy and satire. The Narrator’s limited judgment invites readers to interpret freely. Ultimately, he symbolizes artistic objectivity and moral curiosity. His presence transforms observation into subtle moral participation, defining the poem’s humanistic essence.

29. Symbolism in Characterization

Symbolism deepens characterization across the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer uses clothing, color, and gestures to express moral traits. Moreover, symbols transform ordinary details into ethical commentary. The Knight’s armor, the Monk’s fur, and the Pardoner’s hair reveal character through imagery. Therefore, symbolic expression strengthens realism with moral texture. Furthermore, Chaucer’s visual cues guide readers toward hidden meaning. Each symbol connects virtue or vice to external form. Ultimately, symbolism makes characterization multidimensional, blending art, morality, and observation. Chaucer’s skill lies in uniting physical reality with inner truth.

30. Irony and Contrast in Characters

Irony defines Chaucer’s art of characterization. He praises while mocking, admires while exposing faults. Moreover, contrast among pilgrims reveals diverse human nature. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales explores moral complexity through irony. The Parson’s holiness contrasts the Pardoner’s greed. Furthermore, irony highlights tension between appearance and reality. Chaucer’s humor softens critique, transforming judgment into wisdom. Each contrast adds balance, realism, and insight. Ultimately, irony becomes tool of moral revelation. Through it, Chaucer captures humanity’s blend of virtue, vanity, and vulnerability.

31. Social Diversity in Characterization

Social diversity enriches the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer gathers pilgrims from all classes and professions. Moreover, he unites them through shared storytelling. Therefore, characterization becomes reflection of medieval social order. The Knight and the Miller stand on moral extremes yet share human depth. Furthermore, Chaucer’s fairness bridges rank differences through humor and sympathy. Each character reflects dignity, folly, or moral flaw. Ultimately, social variety creates realism unmatched in medieval literature. Chaucer transforms social observation into moral art, blending equality with satire.

32. Humor in Characterization

Humor gives warmth and accessibility to Chaucer’s portraits. It exposes flaws without cruelty. Moreover, humor creates connection between poet and audience. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses laughter to reveal truth. The Miller’s boast, the Wife’s wit, and the Monk’s indulgence bring vivid energy. Furthermore, humor balances moral seriousness with joy. Chaucer’s gentle satire prevents bitterness, celebrating humanity’s complexity. Each comic detail hides deeper insight. Ultimately, humor shapes characterization as both entertaining and philosophical. Through laughter, Chaucer teaches compassion and self-awareness.

33. Realism in Characterization

Realism anchors Chaucer’s art. His characters speak, act, and think like real people. Moreover, he draws from everyday observation, not mythic idealism. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales achieves timeless authenticity. Furthermore, realism allows moral understanding through ordinary experience. Chaucer portrays motives, emotions, and contradictions honestly. The Knight’s honor, the Pardoner’s greed, and the Plowman’s virtue reveal human diversity. Ultimately, realism makes his poetry modern in spirit. Through truth of detail, Chaucer transforms medieval types into living souls.

34. Language and Dialogue

Chaucer’s dialogue reveals character through tone and speech rhythm. Each pilgrim’s voice reflects education, class, and attitude. Moreover, realistic dialogue creates individuality within unity. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales achieves dynamic liveliness. Furthermore, language serves as moral mirror—honesty, deceit, pride, and humility all appear in speech. Chaucer’s precision in diction transforms description into action. Through linguistic realism, he builds intimacy and irony together. Ultimately, dialogue becomes structural and moral device, defining personality through words rather than exposition.

35. Moral Purpose in Characterization

Moral purpose underlies Chaucer’s entire art. His portraits teach virtue through imperfection. Moreover, humor becomes medium of correction. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales joins moral lesson with entertainment. Furthermore, each character reflects ethical question—honesty, greed, faith, or hypocrisy. Chaucer neither condemns nor idealizes; he understands. His balanced tone humanizes morality. Ultimately, characterization becomes spiritual journey through human flaws. Through this blend of realism and ethics, Chaucer’s work attains universality and grace.

36. Use of Physical Description

Chaucer’s physical details reveal inner character. The Pardoner’s yellow hair, the Miller’s wart, and the Monk’s fatness express moral states. Moreover, description becomes moral code. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales links body and soul symbolically. Furthermore, vivid imagery strengthens satire without cruelty. Each detail deepens understanding through visual truth. Chaucer’s descriptive mastery transforms poetry into portraiture. Ultimately, his physical realism becomes moral revelation, merging artistry with ethical perception.

37. Satire as Characterization Tool

Satire defines Chaucer’s technique of moral critique. He mocks greed, pride, and hypocrisy with wit. Moreover, satire humanizes vice through laughter. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales uses humor to correct rather than condemn. Furthermore, satire exposes contradiction between appearance and virtue. Each pilgrim’s weakness becomes lesson in humility. Chaucer’s restraint keeps satire graceful yet insightful. Ultimately, satire becomes compassionate mirror, blending laughter with moral truth. His art refines judgment through gentle irony.

38. Unity through Characterization

Despite diverse pilgrims, Chaucer creates unity through tone and observation. Moreover, shared journey binds differences within harmony. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales achieves coherence through consistent moral vision. Furthermore, balanced humor maintains equality among characters. Chaucer’s structure reflects humanity’s collective pilgrimage toward truth. Each personality adds depth to shared theme of moral exploration. Ultimately, unity arises from variety itself, proving diversity enriches moral order.

39. Psychological Depth in Characterization

Chaucer’s characters display motives, emotions, and contradictions. He explores ambition, fear, faith, and desire. Moreover, psychological detail anticipates modern fiction. Therefore, the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales surpasses simple portraiture. Furthermore, inner conflict defines realism and empathy. The Wife’s independence and the Pardoner’s guilt reflect inner struggle. Chaucer’s insight reveals soul beneath stereotype. Ultimately, characterization gains timelessness through psychological truth. His art blends observation, intellect, and compassion into living realism.

40. Conclusion

Characterization in Prologue to the Canterbury Tales stands as Chaucer’s greatest artistic triumph. He transforms medieval stereotypes into complex individuals. Moreover, realism and irony coexist within moral design. Therefore, his portrayal of pilgrims defines human diversity and unity. Furthermore, humor enriches insight, turning satire into compassion. Through balanced tone, Chaucer creates both social document and spiritual mirror. Ultimately, The Canterbury Tales endures as masterpiece of character study, where every pilgrim reflects moral truth, poetic beauty, and timeless humanity.

Summary of the General Prologue to the Canterbury Tales:

https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/05/23/prologue-canterbury-tales-summary/

Notes on English for All Classes: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.