Introduction: A Voice of Dissent

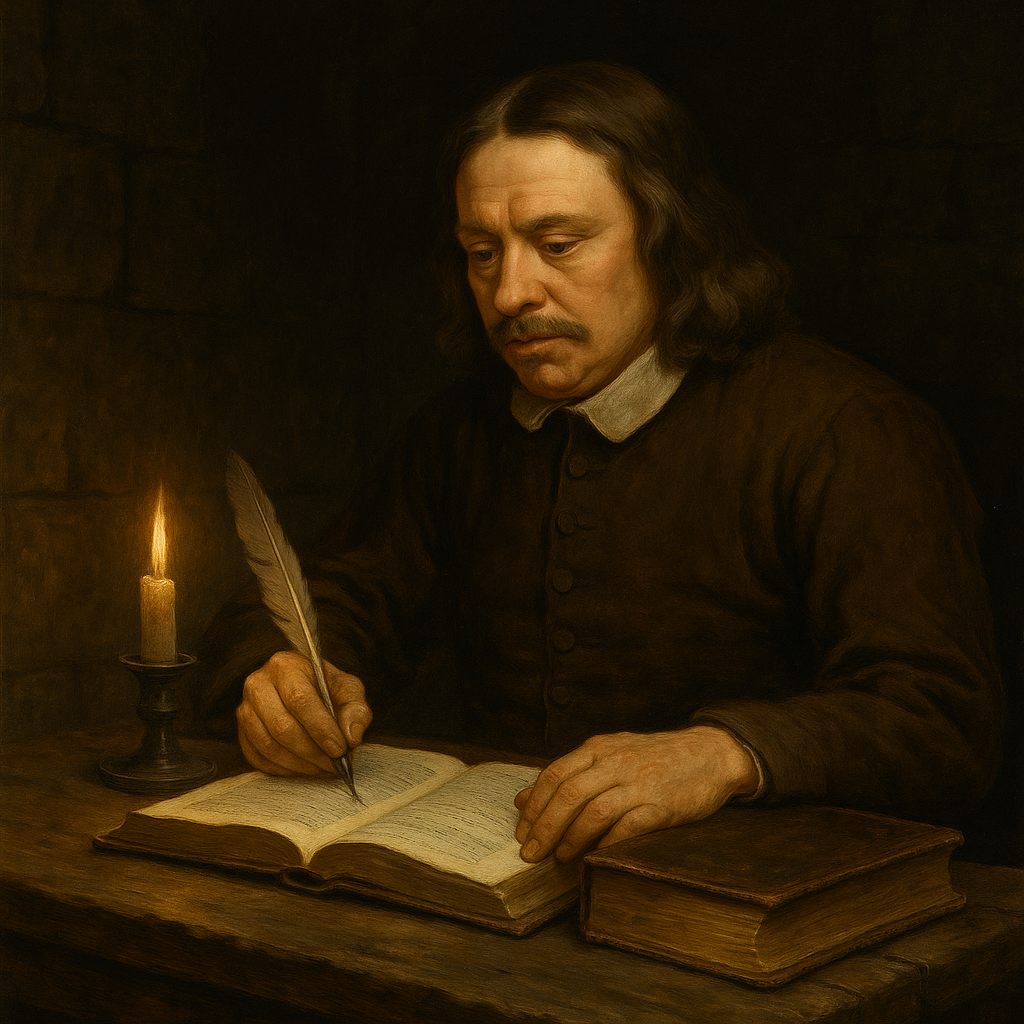

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration represented deep spiritual dissent. Specifically, his earnest piety stood against the court’s light cynicism. Consequently, his writing captured the moral core of the persecuted Dissenters. Moreover, he provided a necessary counterpoint to the era’s fashionable licentiousness. Therefore, he became a powerful symbol of unyielding faith. Furthermore, his experience included long periods of imprisonment. Indeed, the state punished him for preaching his heartfelt beliefs. Thus, his suffering validated his spiritual authority. In short, he articulated the Puritan worldview for generations of readers. Therefore, his famous works defined his literary place. Moreover, his simple prose reached a massive audience. Consequently, his powerful voice echoed far beyond London’s courtly theatres. Indeed, he shaped popular religious thought.

1. The Puritan Heritage

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration upheld a specific religious heritage. Specifically, he inherited the intense spiritual focus of earlier reformers. Consequently, his theology centered on original sin and divine grace. Moreover, he believed deeply in the individual’s direct relationship with God. Therefore, he rejected the hierarchical structure of the restored Anglican Church. Furthermore, he championed the authority of scripture over human tradition. Indeed, his deep study of the Bible shaped his entire worldview. Thus, he preserved the intellectual and moral foundations of Puritanism. Moreover, his work defined the Puritan ethical ideal. Therefore, he passed the core faith to the next generation. Consequently, his writings became essential reading for all Nonconformists. Indeed, he solidified his Puritan identity.

2. Nonconformity and Law

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration directly challenged state law. Specifically, he refused to comply with the Conventicle Act. Consequently, this act prohibited religious assemblies outside the Church of England. Moreover, he saw the law as a direct violation of religious liberty. Therefore, he continued preaching publicly despite the legal threat. Furthermore, this brave disobedience defined his early adult life. Indeed, his activism placed him in constant conflict with local authorities. Thus, his actions became a model of passive resistance. Moreover, his struggles highlighted the political persecution of all Dissenters. Therefore, he showed courage in defending his fundamental rights. Consequently, his stand became a rallying point for the oppressed faithful.

3. The Imprisonment Years

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration endured harsh political imprisonment. Specifically, he spent over twelve years confined in Bedford Gaol. Consequently, this long suffering tested both his faith and his physical health. Moreover, the lack of freedom fueled his desire for spiritual expression. Therefore, he began writing as a way to continue his ministry. Furthermore, the cell became a unique setting for powerful creativity. Indeed, his confinement proved far more productive than his expected freedom. Thus, persecution unintentionally gave birth to his greatest work. Moreover, he demonstrated profound inner strength. Therefore, his prison writings possess undeniable authenticity. Consequently, his harsh experience shaped his spiritual insights.

4. The Genesis of The Pilgrim’s Progress

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration conceived his masterpiece in prison. Specifically, he wrote The Pilgrim’s Progress as a dream vision. Consequently, the confined space forced his imagination into the realm of spiritual journey. Moreover, the allegory provided a safe means to express his religious beliefs. Therefore, he avoided direct political critique through fictional devices. Furthermore, the narrative structure reflected his own experience of spiritual awakening. Indeed, the lack of materials encouraged his reliance on pure, simple invention. Thus, the book emerged from both severe limitation and profound spiritual necessity. Moreover, the allegory proved universally accessible. Therefore, the work secured his literary immortality. Consequently, the book’s creation remains legendary.

5. The Power of Allegory

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration achieved fame using Christian allegory. Specifically, the allegory presented complex theology simply and clearly. Consequently, the narrative used easily understood symbols from common, daily life. Moreover, the book transformed the spiritual journey into a vivid, realistic road. Therefore, the illiterate and scholarly both found the work deeply meaningful. Furthermore, Bunyan’s prose used the rhythms of the Bible. Indeed, his direct style gave the narrative immense dramatic force. Thus, his literary method ensured the widespread transmission of Puritan doctrine. Moreover, he secured his status as a literary master. Therefore, his genius lay in accessible, imaginative storytelling. Consequently, he taught vital lessons to the common people.

6. Christian’s Burden

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration symbolized the weight of sin. Specifically, the character Christian carries a great burden on his back. Consequently, this burden represents the guilt and weight of personal sin. Moreover, Christian’s desperate need for relief drives the entire plot. Therefore, Bunyan immediately establishes the allegory’s core theological theme. Furthermore, the burden symbolizes the universal human experience of guilt. Indeed, Christian’s journey begins only when he recognizes his spiritual need. Thus, Bunyan gave an abstract concept a tangible, heavy form. Moreover, the image instantly resonated with every reader. Therefore, the burden serves as a powerful dramatic device. Consequently, the image explains the source of Christian’s anxiety.

7. The Slough of Despond

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration vividly portrayed spiritual doubt. Specifically, Christian falls early into the Slough of Despond. Consequently, this swamp symbolizes the overwhelming feelings of doubt and fear. Moreover, the Slough represents the despair that can halt a believer’s progress. Therefore, Bunyan showed that the road to faith is difficult and fraught with danger. Furthermore, the help Christian receives emphasizes the necessity of divine grace. Indeed, Bunyan experienced similar periods of intense religious anxiety. Thus, this section possesses deep personal authenticity. Moreover, the image warned readers against spiritual paralysis. Therefore, the Slough became a famous symbol of existential crisis. Consequently, he validated the reader’s own inner struggle.

8. The Simple Prose Style

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration championed a clear, simple prose style. Specifically, his language avoided the witty flourishes of courtly writers. Consequently, he used direct, Anglo-Saxon vocabulary for maximum impact. Moreover, his style made the text instantly accessible to the common reader. Therefore, he defied the elaborate literary fashion of the Restoration era. Furthermore, his prose drew its strength directly from the King James Bible. Indeed, this Biblical simplicity lent his writing profound moral authority. Thus, his style mirrored the spiritual sincerity of his message. Moreover, he believed plain language served the cause of truth. Therefore, his technique was both political and theological. Consequently, the clarity of his writing ensured his popular appeal.

9. Contrast with Restoration Drama

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration offered a moral alternative to courtly drama. Specifically, his themes concerned salvation, not social intrigue. Consequently, his characters showed spiritual depth, not just witty cynicism. Moreover, his audience rarely attended the plays of Congreve or Wycherley. Therefore, his work formed the literary backbone of a thriving counter-culture. Furthermore, his piety stood in direct opposition to the theatres’ moral licence. Indeed, the Puritan rejection of stage plays was a defining cultural stance. Thus, Bunyan’s writing satisfied the demand for morally serious entertainment. Moreover, he gave the pious classes their own compelling literature. Therefore, he provided a powerful alternative to secular art. Consequently, he shaped the reading habits of millions.

10. Grace Abounding

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration provided a personal spiritual record. Specifically, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners served as his autobiography. Consequently, the book detailed his intense struggle with sin and profound doubt. Moreover, the work followed the standard pattern of a Puritan conversion narrative. Therefore, he showed readers the exact path to spiritual awakening. Furthermore, the book achieved immediate success among the faithful. Indeed, its raw honesty made it deeply relatable. Thus, he established a definitive model for Christian experience. Moreover, the autobiography validated his authority as a gifted preacher. Therefore, he offered a powerful testament to the reality of grace. Consequently, his personal story confirmed his sincerity.

11. Vanity Fair

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration satirized the world’s temptations. Specifically, Christian and Faithful visit the bustling, wicked Vanity Fair. Consequently, this annual fair represents the empty materialism and moral corruption of the world. Moreover, Bunyan modeled the Fair on the thriving commercial life of London society. Therefore, he criticized the era’s focus on wealth, fashion, and social status. Furthermore, the townspeople’s cruel persecution of the pilgrims highlights spiritual danger. Indeed, the Fair serves as a powerful allegorical critique of the world’s vanity. Thus, Bunyan warned believers against worldly attachments. Moreover, this section possesses enduring social relevance. Therefore, he showed the conflict between faith and commerce. Consequently, the Fair became a famous cultural symbol.

12. Christian and Faith

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration explored the necessity of true faith. Specifically, Christian embodies the concept of the persistent, seeking believer. Consequently, he represents every individual committed to the spiritual path. Moreover, his companion, Faithful, demonstrates unwavering religious courage. Therefore, the pilgrims rely on scripture and steadfast belief to overcome every obstacle. Furthermore, their devotion contrasts sharply with the worldliness they reject. Indeed, their unity underscores the importance of Christian fellowship. Thus, Bunyan instructed readers in the true practice of piety. Moreover, he showed faith as an active, difficult commitment. Therefore, the characters modeled essential spiritual virtues. Consequently, their determination inspired many readers.

13. The Two Cities

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration structured his tale around two distinct cities. Specifically, the pilgrims start in the City of Destruction. Consequently, this starting point symbolizes humanity’s natural, unredeemed state. Moreover, their destination is the glorious Celestial City. Therefore, this journey represents the path to salvation and eternal life. Furthermore, the contrast between the cities provides the central dramatic tension. Indeed, the stark moral difference guides all the pilgrims’ decisions. Thus, Bunyan simplified the theological concept of heaven and hell. Moreover, he gave the reader a clear moral compass. Therefore, the two cities defined the allegory’s spatial design. Consequently, their symbolic value remains powerful.

14. The Plain Language Bible

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration revered the plain language of the Bible. Specifically, he believed the Scripture was easily accessible to all Christian readers. Consequently, he rejected the need for complex, mediated religious interpretation. Moreover, his prose reflects the simple, narrative clarity of the King James Version. Therefore, his writing made the spiritual journey feel immediate and real. Furthermore, he used Biblical names and allusions extensively throughout the text. Indeed, his deep scriptural knowledge provided the foundation for his entire allegory. Thus, he ensured his voice remained consistent with his religious source. Moreover, he upheld the Puritan emphasis on personal Bible study. Therefore, his language held spiritual authority. Consequently, his work encouraged popular literacy.

15. The Common Man’s Hero

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration created a hero for the common man. Specifically, Christian starts as an ordinary, troubled villager. Consequently, he represents the typical working-class individual seeking salvation. Moreover, this background contrasts with the aristocratic heroes of Restoration drama. Therefore, Bunyan validated the spiritual concerns of the labouring classes. Furthermore, the hero’s simple identity allowed for widespread identification. Indeed, Christian’s struggles reflected the everyday challenges faced by his readers. Thus, Bunyan democratized the heroic spiritual quest. Moreover, he proved that piety transcended social rank. Therefore, his hero provided great moral comfort. Consequently, the common man found his voice in Bunyan.

16. The Holy War

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration wrote a second major allegory. Specifically, The Holy War described the conflict for the human soul. Consequently, the book portrayed the spiritual battle as a siege on the town of Mansoul. Moreover, the complex narrative showed the ongoing spiritual struggle against the devil’s forces. Therefore, Bunyan used military metaphors to describe theological concepts. Furthermore, the work highlighted the constant vigilance required of every believer. Indeed, this allegory showed his imagination’s range and his theological depth. Thus, The Holy War complemented the narrative of The Pilgrim’s Progress. Moreover, he used the book to explain Christian warfare. Therefore, the allegory addressed the intellectual aspect of faith. Consequently, the book further secured his reputation.

17. Antagonists of the Faith

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration populated his work with moral antagonists. Specifically, characters like Ignorance and Worldly Wiseman mislead Christian. Consequently, these figures represent common human faults and theological errors. Moreover, they illustrate the constant temptations that divert the believer. Therefore, Bunyan used them to teach readers to recognize and avoid danger. Furthermore, the antagonists are often subtle, making them more treacherous. Indeed, the character names immediately convey their spiritual flaw. Thus, Bunyan created a vivid rogues’ gallery of spiritual errors. Moreover, their fates served as powerful moral warnings. Therefore, the antagonists defined the perilous nature of the journey. Consequently, he simplified complex moral dilemmas.

18. The Role of the Interpreter

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration emphasized the guidance of the Spirit. Specifically, the Interpreter provides Christian with crucial spiritual lessons. Consequently, the Interpreter’s house serves as a school for divine instruction. Moreover, the Interpreter symbolizes the work of the Holy Spirit. Therefore, Bunyan stressed the need for spiritual understanding of the Scriptures. Furthermore, the lessons prepare Christian for the challenges he will face. Indeed, this character ensures the text remains firmly rooted in Protestant theology. Thus, the Interpreter acts as a necessary mentor on the spiritual path. Moreover, he proves that grace precedes all good works. Therefore, this section underlines the importance of spiritual discernment. Consequently, Bunyan guided his readers carefully.

19. Dissenting Audience

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration primarily reached a dissenting audience. Specifically, his readers were the persecuted lower and middle classes. Consequently, these groups found their values validated in his earnest prose. Moreover, his work served as comfort and instruction during times of political stress. Therefore, his writing became a staple in Nonconformist and Baptist homes. Furthermore, his popularity reflected the deep spiritual needs ignored by courtly literature. Indeed, his works outsold the famous literary dramas of the period. Thus, his writing proved the economic and cultural power of religious dissent. Moreover, he solidified the cultural identity of the common faithful. Therefore, his popularity was a form of political statement. Consequently, his readership was immense.

20. The Market for Salvation

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration offered a market for salvation. Specifically, the success of his book created a thriving market for pious literature. Consequently, booksellers rushed to print countless editions of his most famous work. Moreover, his writing confirmed the commercial viability of religious themes. Therefore, he demonstrated that spiritual concerns held mass consumer appeal. Furthermore, his widespread circulation required innovative printing and distribution methods. Indeed, his popularity helped develop the modern publishing industry. Thus, his theology shaped both the spiritual and commercial landscape. Moreover, he proved that religious zeal drove cultural consumption. Therefore, his book became a commercial phenomenon. Consequently, his writing reached millions globally.

21. The Wicket Gate

John Bunyan as Puritan Voice of the Restoration illustrated the difficulty of initial commitment. Specifically, Christian must find and enter the narrow Wicket Gate. Consequently, this small opening symbolizes the strictness of Christ’s call to faith. Moreover, the narrowness emphasizes the difficulty of abandoning a sinful life. Therefore, Bunyan showed that the path to salvation begins with a deliberate, hard choice. Furthermore, the gate also symbolizes repentance and genuine conversion. Indeed, finding the gate required guidance and persistent effort. Thus, the Wicket Gate became an enduring image of spiritual initiation. Moreover, he warned against false or easy entries. Therefore, the image stressed the seriousness of true faith. Consequently, the gate marks the true beginning.

22. The House Beautiful

Bunyan depicted the importance of Christian community. Specifically, the House Beautiful provides the pilgrims with much-needed rest and refreshment. Consequently, this house symbolizes the church and fellowship of believers. Moreover, the residents offer spiritual guidance and material aid. Therefore, Bunyan stressed that no believer should undertake the journey alone. Furthermore, the house represents the necessary support structure of organized faith. Indeed, the rest they receive fortifies them for later, harder trials. Thus, Bunyan showed that community provides essential spiritual nourishment. Moreover, the house offered a glimpse of heavenly glory. Therefore, this location became a vital symbolic stop. Consequently, the house underscores Christian hospitality.

23. Apollyon’s Challenge

Bunyan portrayed the battle against evil. Specifically, Christian engages in a fierce fight against the demon Apollyon. Consequently, Apollyon represents the devil’s direct attempt to reclaim the believer’s soul. Moreover, the intense combat underscores the spiritual reality of the continuous struggle. Therefore, Bunyan proved that true faith requires active spiritual warfare. Furthermore, Christian’s eventual victory relies solely on the shield of Faith. Indeed, this scene became one of the book’s most famous dramatic moments. Thus, Bunyan gave the devil a tangible, terrifying form. Moreover, the fight showed the power of steadfast resistance. Therefore, this allegory stressed constant vigilance against temptation. Consequently, the battle affirmed Christian’s courage.

24. Simplicity in Character Names

Bunyan used simple, descriptive character names. Specifically, figures like Pliable, Formalist, and Hypocrisy reveal their entire nature. Consequently, the names served as immediate moral and spiritual labels. Moreover, this technique simplified complex moral states for the common reader. Therefore, Bunyan ensured that his theological message remained perfectly clear. Furthermore, this naming convention became a hallmark of early English satire. Indeed, the names leave no doubt about the characters’ ultimate spiritual fate. Thus, Bunyan ensured his book functioned as a simple moral guide. Moreover, the technique showed his genius for plain literary craft. Therefore, the names drove the story’s ethical point. Consequently, his literary method was highly didactic.

25. The Moral Didacticism

Bunyan employed clear moral didacticism. Specifically, the book openly aimed to instruct readers in correct spiritual behavior. Consequently, every scene and character serves a definite, instructive purpose. Moreover, the narrative warns, advises, and comforts the reader at every turn. Therefore, Bunyan placed theological instruction above mere literary entertainment. Furthermore, his belief in scripture’s authority fueled his strong teaching method. Indeed, his work functioned as a practical handbook for Christian living. Thus, he used his artistry to serve a strictly religious aim. Moreover, the didactic nature contributed to its enormous popularity. Therefore, he made theology accessible and relevant. Consequently, the book’s purpose was purely instructional.

26. Escape from Literalism

Bunyan used allegory to escape literal persecution. Specifically, the dream format provided a necessary artistic shield. Consequently, he could criticize the political and moral failings of the era subtly. Moreover, the story of religious pilgrims facing hardship offered veiled social commentary. Therefore, the allegory allowed him to speak truth without directly breaking the law. Furthermore, the fictional journey protected him from direct charges of political sedition. Indeed, the literary device became a safe space for dissent and critique. Thus, Bunyan successfully outmaneuvered the strict legal constraints. Moreover, his creative tactic saved him from further imprisonment. Therefore, allegory proved an essential survival tool. Consequently, his technique showed great cunning.

27. The Worldly Wiseman

Bunyan criticized misguided secular advice. Specifically, Mr. Worldly Wiseman attempts to divert Christian from the correct path. Consequently, this character represents the temptation of taking an easier, less spiritual route. Moreover, the Wiseman embodies legalism and reliance on human reason. Therefore, Bunyan showed that secular wisdom often proves spiritually dangerous. Furthermore, he warned against substituting worldly convenience for strict Puritan piety. Indeed, the Wiseman’s advice almost leads Christian to his own ruin. Thus, Bunyan stressed adherence to scripture over human logic. Moreover, the Wiseman symbolized the false doctrines of the Church. Therefore, he exposed the error of relying on mere prudence. Consequently, the encounter served as a powerful warning.

28. The Palace Beautiful

Bunyan depicted the church’s protective role. Specifically, the Palace Beautiful represents the visible, true Christian church. Consequently, the Palace offers protection from the dangers outside its walls. Moreover, the pilgrims receive rest, fellowship, and crucial spiritual weapons. Therefore, Bunyan underlined the necessity of church membership for the believer’s safety. Furthermore, the house represents the necessary support structure of organized faith. Indeed, the rest they receive fortifies them for later, harder trials. Thus, Bunyan showed that community provides essential spiritual nourishment. Moreover, the Palace offered a glimpse of heavenly glory. Therefore, this location became a vital symbolic stop. Consequently, the Palace underscores Christian hospitality.

29. The Use of Dialogue

Bunyan used dialogue effectively to advance the plot. Specifically, conversations between characters reveal their spiritual state. Consequently, the dialogue serves as a direct vehicle for theological and moral debate. Moreover, the language remains simple, reflecting the speech of the common people. Therefore, his conversational style contributed significantly to the book’s narrative flow. Furthermore, the dialogue contrasts sharply with the rhetorical excesses of courtly prose. Indeed, the simple exchanges drive the action forward with great clarity. Thus, Bunyan ensured that his readers understood every spiritual point. Moreover, the dialogue deepened the characters’ individual natures. Therefore, his use of speech was highly naturalistic. Consequently, his writing felt truly alive.

30. The Valley of Humiliation

Bunyan stressed the importance of humility. Specifically, Christian passes through the terrifying Valley of Humiliation. Consequently, this dark valley symbolizes the necessary breaking of personal pride. Moreover, the valley is the site of his fierce battle with Apollyon. Therefore, Bunyan showed that spiritual victory requires absolute lowliness of mind. Furthermore, humility protects the believer from the most dangerous spiritual temptations. Indeed, the valley is less dangerous than the later Valley of the Shadow of Death. Thus, Bunyan demonstrated that acknowledging one’s weakness leads to strength. Moreover, the valley served as a major turning point. Therefore, he made humility a core Puritan virtue. Consequently, the passage taught a vital lesson.

31. The Valley of the Shadow of Death

Bunyan depicted the trial of profound fear. Specifically, Christian must traverse the terrible Valley of the Shadow of Death. Consequently, this valley represents the ultimate test of the believer’s courage and faith. Moreover, the valley symbolizes the fear of death, hell, and divine judgment. Therefore, Bunyan used vivid imagery of darkness, danger, and demonic voices. Furthermore, the pilgrim navigates this horror solely by the guidance of his faith. Indeed, this section provides the story’s most intense dramatic climax. Thus, Bunyan showed that the greatest spiritual dangers are often internal. Moreover, the valley affirmed the power of persistent prayer. Therefore, the passage became a famous symbol of existential terror. Consequently, he validated the darkest fears of his readers.

32. Hopeful as Companion

Bunyan introduced the vital companion Hopeful. Specifically, Hopeful replaced Faithful, who suffered martyrdom in Vanity Fair. Consequently, Hopeful embodies the necessity of sustained expectation in the spiritual life. Moreover, he helps Christian through the final, most treacherous trials. Therefore, Bunyan showed that Christian reliance on fellowship remains essential. Furthermore, Hopeful’s own conversion story provides deep spiritual instruction. Indeed, their shared struggles strengthen both men’s resolve and piety. Thus, the companionship underscores the importance of mutual support. Moreover, Hopeful prevents Christian from falling into total despair. Therefore, he proves that grace brings necessary renewal. Consequently, the character became a symbol of divine mercy.

33. Doubting Castle and Giant Despair

Bunyan explored the paralysis of doubt. Specifically, Christian and Hopeful are captured by Giant Despair. Consequently, they are imprisoned within the terrifying walls of Doubting Castle. Moreover, this episode symbolizes the spiritual bondage caused by lack of faith. Therefore, the Giant tempts them toward suicide as their only release. Furthermore, their escape relies on the timely discovery of the Key of Promise. Indeed, the key represents the power of God’s word and divine assurance. Thus, Bunyan showed that despair is a literal, tangible prison. Moreover, he emphasized that God’s promises always unlock spiritual freedom. Therefore, the castle became a powerful image of spiritual entrapment. Consequently, the story teaches reliance on scripture.

34. The Key of Promise

Bunyan highlighted the certainty of God’s word. Specifically, the Key of Promise unlocks the doors of Doubting Castle. Consequently, this key symbolizes the concrete, reliable truth found in the Holy Bible. Moreover, its discovery proves that deliverance from despair is always possible. Therefore, Bunyan stressed that believers must actively remember and apply God’s promises. Furthermore, the Key contrasts with the human error of reliance on mere reason. Indeed, the simple act of remembering a scripture saves the pilgrims from ruin. Thus, Bunyan affirmed the literal, saving power of divine revelation. Moreover, the key showed the spiritual importance of Biblical memory. Therefore, the image offered profound comfort to all readers.

35. By-Path Meadow

Bunyan warned against seeking easy paths. Specifically, Christian and Hopeful leave the narrow road for By-Path Meadow. Consequently, this detour symbolizes the temptation of convenience over strict piety. Moreover, the meadow represents spiritual shortcuts that seem safe but lead to danger. Therefore, their transgression leads directly to their capture by Giant Despair. Furthermore, this episode emphasizes the constant need for vigilance and strict adherence to the path. Indeed, Bunyan showed that even experienced pilgrims can make careless errors. Thus, the meadow serves as a potent warning against spiritual complacency. Moreover, he stressed that the correct way often feels more difficult. Therefore, the detour provides a painful moral lesson.

36. The Enduring Popularity

Bunyan achieved massive, enduring popularity. Specifically, his book has remained continuously in print since its first publication. Consequently, it became one of the most widely read books in the entire English language. Moreover, its appeal crossed national boundaries and social classes. Therefore, the simple narrative proved universally relatable across many cultures. Furthermore, his work provided essential reading for common, working-class people. Indeed, the book’s success demonstrated the spiritual depth of the non-aristocratic audience. Thus, Bunyan’s voice defined the spiritual reading habits of the English-speaking world. Moreover, he achieved literary fame without any courtly patronage. Therefore, his legacy proved truly democratic.

37. Martyrdom in Vanity Fair

Bunyan showed the cost of faith. Specifically, the character Faithful endures torture and dies in Vanity Fair. Consequently, his martyrdom symbolizes the brutal persecution faced by religious Dissenters. Moreover, this event highlights the hostility of the secular world towards true piety. Therefore, Bunyan validated the real-life suffering of his fellow Nonconformists. Furthermore, Faithful’s death proves that spiritual commitment requires ultimate sacrifice. Indeed, the violent scene serves as a powerful testament to the truth of his faith. Thus, Bunyan used fiction to honor those who died for their beliefs. Moreover, his death strengthens Christian’s own resolve to continue. Therefore, martyrdom provides a necessary moral climax.

38. The Celestial City

Bunyan provided a glorious spiritual goal. Specifically, the Celestial City represents the heavenly culmination of the entire journey. Consequently, the city symbolizes eternal life, salvation, and divine glory. Moreover, the pilgrims’ arrival marks the end of all earthly struggle and suffering. Therefore, Bunyan rewarded the reader’s perseverance with a vision of ultimate joy. Furthermore, the beautiful, heavenly gates contrast sharply with the grim City of Destruction. Indeed, the Celestial City provided powerful motivation for all believing readers. Thus, Bunyan fulfilled the deep eschatological hope of the Puritan spirit. Moreover, the vision confirmed the literal truth of his theology. Therefore, the ending offered profound spiritual comfort.

39. The Secularization of Allegory

Bunyan influenced the secular novel. Specifically, later writers adapted his allegorical techniques to worldly themes. Consequently, his focus on the individual’s linear journey became a standard literary model. Moreover, the structure of his spiritual quest informed picaresque and adventure stories. Therefore, authors began detailing the common man’s struggle through material and social worlds. Furthermore, the vivid realism of his descriptive scenes lent itself easily to secular fiction. Indeed, his prose style provided a model for later journalistic realism. Thus, Bunyan’s religious art inadvertently pioneered the modern literary form. Moreover, he showed how narrative realism could convey deep meaning. Therefore, his influence extends far beyond mere theology.

40. Literary Influence on Defoe

Bunyan directly influenced Daniel Defoe. Specifically, Defoe, himself a Dissenter, greatly admired Bunyan’s prose. Consequently, Defoe’s realism and focus on the practical individual mirror Bunyan’s style. Moreover, the isolating journey of Robinson Crusoe reflects the spiritual isolation of Christian. Therefore, Defoe adapted the spiritual autobiography into a form of economic and social narrative. Furthermore, both writers used plain, unadorned language to appeal to the emerging middle class. Indeed, Bunyan provided a foundational model for the modern novel’s realistic detail. Thus, his work helped shape the next generation of English fiction. Moreover, he linked Puritanism to the rise of literary realism. Therefore, his genius directly fueled Defoe’s successes.

41. The Simplicity of Truth

Bunyan emphasized the simplicity of truth. Specifically, he believed spiritual truths required no complex philosophical systems. Consequently, his straightforward prose reflected his conviction that God’s word was easily understood. Moreover, he rejected the academic intellectualism favored by Anglican scholars. Therefore, his writing appealed directly to the heart and common sense. Furthermore, his theological clarity stood in stark contrast to the era’s skeptical debates. Indeed, this simplicity made his spiritual message instantly credible. Thus, he proved that profound wisdom lay in accessible, plain language. Moreover, he maintained the Puritan distrust of human learning. Therefore, his genius lay in spiritual directness. Consequently, his work bypassed elite circles.

42. The Role of Personal Experience

Bunyan validated personal religious experience. Specifically, his work centered on the internal, subjective struggle for faith. Consequently, he showed that salvation was a deeply personal and emotional process. Moreover, his autobiography detailed his own severe bouts of spiritual doubt. Therefore, he legitimized the intense feelings of anxiety and profound guilt. Furthermore, this focus contrasted sharply with the external rituals of the established church. Indeed, the Puritan emphasis on individual conversion drove his entire narrative. Thus, Bunyan empowered the reader’s own spiritual journey. Moreover, he made internal feelings the basis of theological truth. Therefore, his authenticity resonated with deep spiritual need. Consequently, his writing felt deeply real.

43. The Baptist Affiliation

Bunyan belonged to the Baptist tradition. Specifically, he championed the Puritan belief in believer’s baptism. Consequently, he rejected the Anglican practice of infant baptism. Moreover, his church was a Nonconformist congregation outside the official state church. Therefore, his allegiance reinforced his position as a religious dissenter. Furthermore, his fellowship provided the spiritual support necessary for his ministry. Indeed, the Baptists were among the most persecuted groups during the entire Restoration. Thus, Bunyan’s work became the quintessential literary expression of the persecuted Baptists. Moreover, his sermons cemented his position as a Baptist leader. Therefore, his religious context explains his political persecution. Consequently, he gave the Baptists a voice.

44. The Economic Context of Dissent

Bunyan emerged from a specific economic class. Specifically, he worked as a simple tinker, reflecting his humble origins. Consequently, his working-class background lent credibility to his message among the poor. Moreover, his audience consisted mainly of tradesmen, artisans, and the lower middle class. Therefore, his popularity demonstrated the cultural power of this emerging segment. Furthermore, the Dissenters often excelled in commerce and lacked aristocratic patronage. Indeed, their economic independence fueled their desire for religious and political freedom. Thus, Bunyan’s voice embodied the spirit of the financially and spiritually independent. Moreover, he linked Puritanism to the rise of commercial values. Therefore, his work possessed strong socio-economic relevance.

45. The Trial and Testimony

Bunyan faced a crucial trial for his preaching. Specifically, his court appearance demonstrated his refusal to compromise his faith. Consequently, his defiant testimony became legendary among Nonconformist circles. Moreover, he argued that God, not the King, possessed ultimate spiritual authority. Therefore, his courage highlighted the fundamental conflict between state power and individual conscience. Furthermore, the trial set the stage for his twelve years of imprisonment. Indeed, his principled stand secured his moral authority as a dissenting leader. Thus, Bunyan transformed a legal defeat into a spiritual victory. Moreover, his example inspired countless other Dissenters. Therefore, his trial defined his prophetic role.

46. The Restoration Act of Uniformity

Bunyan directly opposed the Act of Uniformity (1662). Specifically, this act required Anglican ordination for all public ministers. Consequently, the Act forced over two thousand Puritan ministers from their pulpits. Moreover, Bunyan viewed the Act as a tyrannical imposition on religious worship. Therefore, his continued illegal preaching was a direct response to this state oppression. Furthermore, the Act effectively created the powerful social class of religious Dissenters. Indeed, his imprisonment resulted directly from his refusal to submit to this legislation. Thus, Bunyan’s life became an active protest against mandated religious conformity. Moreover, he symbolized the enduring strength of the ejected clergy. Therefore, his struggle defined the Act’s social impact.

47. The Literary Device of the Dream

Bunyan used the ancient device of the dream. Specifically, the entire narrative of The Pilgrim’s Progress is presented as a dream seen by the narrator. Consequently, the device lends the story an aura of spiritual mystery and profound revelation. Moreover, the dream structure allowed him to blend realistic detail with allegorical meaning. Therefore, he could present theological truths with imaginative freedom. Furthermore, the device was a common convention in earlier medieval literature. Indeed, the dream provided a safe narrative framework for his controversial message. Thus, Bunyan anchored his modern allegory in traditional literary form. Moreover, the dream emphasized the divine origin of the story. Therefore, the frame enhanced the book’s spiritual authority.

48. Christian’s Physical Realism

Bunyan employed a strong degree of physical realism. Specifically, his descriptions of the road, weather, and physical labor feel intensely vivid. Consequently, this grounding in sensory detail made the spiritual journey feel concrete and immediate. Moreover, the pilgrims struggle with hunger, sleep, and physical fatigue. Therefore, Bunyan ensured that his readers understood the real-world difficulty of the spiritual path. Furthermore, this realism contrasts sharply with the purely abstract nature of earlier religious allegories. Indeed, this tactile honesty became a crucial element influencing later realistic fiction. Thus, Bunyan mastered the art of making theology truly tangible. Moreover, the physical hardship strengthened the moral lesson. Therefore, his realism became his signature style.

49. Influence on World Literature

Bunyan profoundly influenced world literature. Specifically, The Pilgrim’s Progress was translated into over two hundred languages. Consequently, its narrative structure and moral themes spread across global literary cultures. Moreover, writers from Nathaniel Hawthorne to C.S. Lewis acknowledged his deep impact. Therefore, his book became a universal model for stories about trials, journeys, and personal growth. Furthermore, the spiritual allegory proved adaptable to countless cultural and political contexts. Indeed, the book’s simple message allowed for profound cross-cultural resonance. Thus, Bunyan achieved truly global literary prominence. Moreover, his work remains a pillar of English literary history. Therefore, his genius transcended national boundaries.

50. Conclusion: Enduring Voice

Bunyan commands an enduring literary legacy. Specifically, his masterpiece remains a cornerstone of English literature. Consequently, his simple yet powerful prose ensured his immense popularity across all social strata. Moreover, his spiritual allegory continues to resonate with modern readers. Therefore, he stands as a testament to the power of faith and personal conviction. Furthermore, his life demonstrated profound resistance to state authority. Indeed, he provided a vital, moral narrative during a cynical political era. Thus, Bunyan’s voice transcended his own turbulent historical period. Therefore, his work confirmed the vitality of the Puritan spirit. Moreover, he achieved lasting literary greatness. Consequently, his enduring message continues to inspire.

John Vanburg Restoration Dramatist: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/06/30/john-vanbrugh-restoration-dramatist/

Post Modern American Literature: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/postmodern-american-literature/

Application for Readmission: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/20/application-for-readmission/

Subject-Verb Agreement: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/subject-verb-agreement-complete-rule/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.