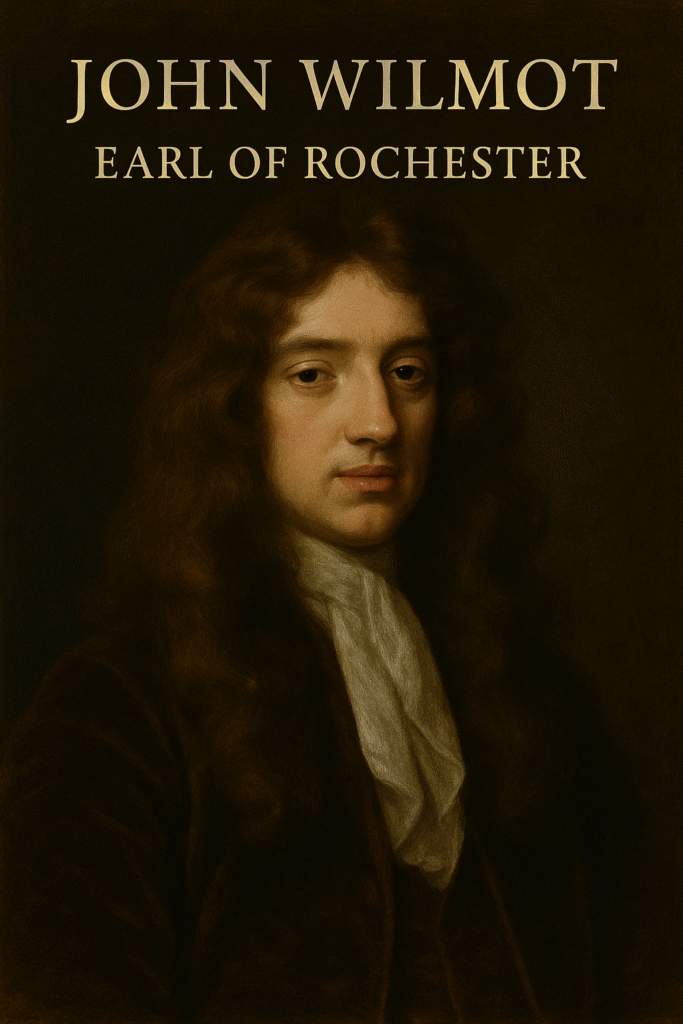

Early Life and Family Background

John Wilmot was born in 1647 into a noble family with strong ties to the monarchy. His father, a Royalist soldier, gave him early exposure to loyalty, conflict, and political engagement. These experiences shaped his worldview, embedding rebellion alongside admiration for order. Moreover, his aristocratic environment offered him privilege and education. Young Wilmot grew up surrounded by expectations of refinement, wit, and leadership. His early experiences sowed seeds of curiosity and daring. Consequently, his personality combined boldness with sharp intelligence. Family heritage gave him confidence to critique society from within. However, noble birth also imposed burdens. People expected him to embody courtly ideals. Instead, he chose provocation and satire. The contradictions in his upbringing fed his artistic voice. Early life thus prepared him to challenge convention. It gave him grounding for the bold choices that later defined his career.

Education and Oxford Years

John Wilmot studied at Wadham College, Oxford, where his wit impressed tutors and peers. He absorbed classical literature, philosophy, and rhetoric with eagerness. These foundations trained him to shape satire with brilliance. His exposure to diverse intellectual debates sharpened both mind and tongue. Importantly, education fueled his questioning spirit. He became skilled in examining morals, politics, and religion through critical lenses. Furthermore, Oxford years expanded his network. He encountered future courtiers, writers, and thinkers. Such circles strengthened his confidence as a provocateur. While others embraced conformity, he chose disruption. Moreover, he developed fascination with libertine ideals—pleasure, skepticism, and wit. His time at Oxford shaped his style of irreverent sophistication. The environment encouraged experiments in verse and thought. Thus, his education not only polished skills but also emboldened rebellion. His Oxford years prepared him for a lifetime of literary controversy.

Introduction to Court Life

After Oxford, John Wilmot entered the court of Charles II, a world buzzing with wit, rivalry, and excess. Court life encouraged daring humor, satire, and public display. Wilmot thrived in this environment, using intellect and boldness to gain recognition. He quickly became known for sharp verses and cutting observations. Courtiers admired his ability to mock hypocrisy while entertaining audiences. Moreover, he cultivated a reputation for fearless expression. Courtly culture valued brilliance, yet demanded loyalty and caution. However, Wilmot pushed boundaries with provocative lines and dangerous satire. His quick wit made him an admired yet feared figure. Furthermore, alliances with fellow libertines expanded his reputation as a daring thinker. Court life thus gave him a stage for talent and controversy. It magnified his contradictions: loyal courtier and merciless critic. This stage prepared him for fame, scandal, and enduring literary significance.

Libertinism and Personal Philosophy

Libertinism defined John Wilmot both personally and poetically. He embraced ideals of pleasure, freedom, and skepticism toward authority. His works reflected irreverence for morality, religion, and convention. He questioned institutions, especially those claiming divine or moral legitimacy. Moreover, libertinism celebrated bodily experience, sensual enjoyment, and rebellion against restraint. Wilmot’s poetry expressed these values with wit and daring. He mocked hypocrisy, exposing contradictions between public virtue and private vice. Furthermore, his libertine stance made him both admired and condemned. Admirers saw courage, while critics saw dangerous immorality. His philosophy offered freedom but also chaos. He lived passionately, often recklessly, defying norms that restricted expression. Moreover, libertinism allowed him to critique power with fearless candor. His personal philosophy blurred boundaries between life and art. Thus, Wilmot became emblematic of Restoration libertinism, shaping English literature with radical honesty. Libertinism gave him identity and enduring influence.

Satirical Voice and Style

Satire formed the essence of John Wilmot’s poetry. His sharp wit and fearless observations targeted politics, morality, and human folly. He wielded words like weapons, striking with precision and irony. Moreover, his satire balanced elegance with brutality. He could amuse while wounding deeply. Restoration audiences craved satire, and Wilmot delivered it boldly. His verses exposed hypocrisies within court, church, and social behavior. Furthermore, his style combined classical learning with colloquial sharpness. He blended elegance with street-level realism. Satirical voice gave him power to challenge kings and clerics alike. Yet it also exposed him to danger. His daring critiques often strained relationships. Nevertheless, his biting humor made him unforgettable. He mastered the art of ridicule while retaining poetic brilliance. Satirical poetry solidified his place as a Restoration giant. It showcased courage, wit, and relentless honesty. Through satire, Wilmot cemented his literary legacy.

Relationship with King Charles II

John Wilmot enjoyed a complex relationship with King Charles II. The king admired his wit and courage, often rewarding him with attention. However, Wilmot’s satire sometimes targeted royal policies, provoking discomfort. This balance of admiration and risk defined their interactions. Moreover, Charles valued cleverness, which Wilmot provided abundantly. He entertained the court while pushing boundaries of acceptable speech. Furthermore, their bond reflected Restoration culture itself—glorious yet precarious. Loyalty often clashed with candor in Wilmot’s career. He exemplified this tension by daring to mock royal authority. Yet he never fully lost favor, demonstrating his resilience. His ability to charm softened criticism. Importantly, Wilmot’s ties to the king secured influence and recognition. However, constant testing of limits invited scandal. Thus, his relationship with Charles was a dance of wit and risk. It defined his prominence and reflected Restoration complexities.

Friendships and Rivalries

John Wilmot formed notable friendships and rivalries within literary and courtly circles. He shared camaraderie with fellow libertines, who admired his daring humor. Their gatherings celebrated wit, drink, and bold conversation. Moreover, these alliances strengthened his cultural presence. Yet rivalry also marked his career. He clashed with figures who disliked his critiques. His sharp tongue often sparked feuds, sometimes violent. Furthermore, rivalry fueled creativity. His biting verses grew sharper when directed against opponents. Friendships, however, offered support and inspiration. Writers such as George Etherege shared similar libertine ideals. Together, they cultivated a culture of satire and rebellion. Moreover, rivals challenged Wilmot to refine arguments and sharpen style. The mix of friendship and enmity enriched his literary environment. Thus, relationships shaped his art as much as philosophy. His social world reflected both camaraderie and conflict, key forces in Restoration creativity.

Major Poems and Themes

John Wilmot’s poetry ranged from scathing satire to erotic verse and philosophical reflection. His themes included hypocrisy, human weakness, love, and mortality. Moreover, he explored contradictions between desire and restraint. His works often mocked moral pretenses while celebrating physical passion. Satire remained constant, yet themes shifted with mood. Furthermore, his poems revealed both cynicism and sensitivity. He challenged religious dogma, exposing flaws in blind faith. Yet he also acknowledged human vulnerability before death. Such duality made his work enduring. Audiences admired his sharpness yet recognized deeper struggles. His poetry balanced rebellion with reflection. Moreover, his works engaged with both court culture and universal questions. This breadth made him versatile and influential. He combined personal experience with social critique. Through major poems, Wilmot shaped Restoration literature. His themes reflected his libertine philosophy, yet also humanized him. His poetry remains complex, daring, and thought-provoking.

Dramatic Works and Prose

Though best remembered as a poet, John Wilmot also engaged with drama and prose. He contributed plays that explored wit, satire, and libertine ideals. Moreover, he wrote prose satires exposing hypocrisy and human folly. His dramatic works reflected Restoration theater’s energy and boldness. Furthermore, his involvement in multiple genres demonstrated versatility. Drama allowed him to bring satire onto stage. Audiences encountered his biting humor through characters and dialogue. His prose, meanwhile, blended sharp observation with philosophical questioning. These works extended his critique beyond poetry. Although drama did not bring him the fame of verse, it enriched his portfolio. Moreover, Wilmot’s ability to adapt across forms showed literary range. He never limited himself to one genre. Instead, he experimented boldly. This openness strengthened his reputation as a daring writer. His plays and prose confirm his cultural importance in Restoration England.

Libertinism and Sexuality

John Wilmot became notorious for libertine sexuality, often celebrated and condemned. His works openly explored physical pleasure, mocking conventional morality. He challenged boundaries between art and life, weaving personal indulgence into verse. Moreover, he embodied the libertine rejection of restraint. His poems depicted sexual passion with wit and frankness. Furthermore, he exposed hypocrisy by contrasting private desires with public virtue. This boldness shocked many contemporaries. Critics saw immorality, yet admirers saw honesty. His libertine sexuality represented both rebellion and truth-telling. Moreover, it influenced Restoration literature by normalizing frank discussion of desire. He made sexuality central to cultural debate. His works highlighted contradictions of a society preaching virtue while practicing indulgence. Thus, his libertinism became both scandalous and symbolic. Sexuality shaped his identity as poet and provocateur. Through this lens, Wilmot remains a bold voice of Restoration rebellion.

Religious Skepticism

Religious skepticism permeated John Wilmot’s writings. He questioned dogma, mocked clerics, and challenged divine authority. Moreover, he doubted the sincerity of religious devotion. His works exposed hypocrisy among those preaching morality. He revealed the gap between faith and practice. Furthermore, he embodied libertine skepticism, prioritizing reason over revelation. His skepticism reflected broader Restoration questioning of authority. Yet it also expressed personal rebellion. He sought freedom from spiritual and institutional control. Critics saw blasphemy, while admirers saw intellectual courage. His skepticism sparked controversy, yet it also revealed honesty. He admitted uncertainty in confronting mortality and meaning. Moreover, his doubts made him relatable. Human fragility before faith and death resonated deeply. His works gave voice to struggles of belief and disbelief. Thus, Wilmot’s skepticism enriched his poetry. It challenged audiences to think critically about religion, morality, and authority.

Political Satire

Political satire marked much of John Wilmot’s poetry. He critiqued policies, courtiers, and even monarchs. His sharp observations exposed corruption and incompetence. Moreover, satire became his tool for challenging authority. He questioned political motives and mocked self-serving leaders. Furthermore, his wit entertained audiences while sparking discomfort among elites. Political satire gave him power to address issues indirectly. He used humor to veil serious critique. Yet rulers often recognized the sting behind his words. His daring made him both admired and feared. Moreover, his satire reflected libertine skepticism toward power. He distrusted authority, exposing its flaws through ridicule. This role placed him at cultural crossroads—loyal nobleman yet merciless critic. Political satire defined his contribution to public debate. His verses remain striking examples of courage in literature. Through satire, Wilmot fused art with social criticism, shaping Restoration culture.

Intellectual Rebellion

Intellectual rebellion defined John Wilmot’s career. He challenged conventions in morality, religion, politics, and art. His works reflected fearless inquiry and defiance. Moreover, he exposed hypocrisy by refusing to conform. His rebellion combined wit with deep thought. He questioned accepted truths, demanding honesty in human discourse. Furthermore, he embraced risk, knowing his words invited backlash. Rebellion was both personal philosophy and literary method. He resisted authority while celebrating reason. Intellectual rebellion shaped his legacy as more than a poet. He symbolized courage in confronting society’s contradictions. Moreover, his defiance inspired later writers to challenge norms. Through rebellion, Wilmot shaped English literary tradition. He offered a model of bold inquiry, unafraid of consequence. His intellectual independence remains relevant. It demonstrates the enduring need for fearless voices. Wilmot’s rebellion thus made him iconic. He embodied Restoration wit, daring, and resistance.

Influence on Restoration Literature

John Wilmot’s works deeply influenced Restoration literature. His sharp satire, libertine themes, and fearless wit set new standards. Moreover, his daring encouraged others to push boundaries. Writers such as Etherege and Rochester echoed his style. Furthermore, his poetry captured the spirit of Restoration culture—irreverent, lively, and bold. He showed literature could balance elegance with rawness. His blending of classical learning with contemporary slang inspired future poets. Moreover, his fearless approach to sexuality and politics widened subjects for literary exploration. Audiences embraced his daring as part of Restoration identity. His influence extended beyond contemporaries. Later generations recognized his innovation and courage. He transformed expectations of satire and wit. His impact lay not only in content but in attitude. Wilmot redefined Restoration poetry. He made literature a tool of critique and rebellion. His influence remains enduring, shaping English letters with brilliance.

Decline and Illness

Later in life, John Wilmot faced decline and illness, consequences of excess and libertine living. His health deteriorated, affecting energy and productivity. Moreover, reckless choices caught up with him. Drinking, indulgence, and reckless living weakened body and spirit. Yet even in decline, his wit persisted. He continued to engage with debates, though weakened physically. Furthermore, illness deepened his reflections on mortality. His later writings showed increased seriousness. They revealed vulnerability behind the bravado. Moreover, his decline symbolized costs of libertine philosophy. He lived intensely, yet paid dearly. His illness did not erase legacy, however. Instead, it added poignancy to his story. His struggles mirrored themes in his poetry—pleasure, fragility, and death. Decline gave depth to his legend. It reminded audiences of human limits. Thus, his illness marked the final chapter of a brilliant yet turbulent life.

Conversion and Final Days

During his final days, John Wilmot reportedly experienced conversion to Christianity. Accounts describe his repentance after illness and reflection. Some claim sincerity, while others question its truth. Nevertheless, these stories shaped his legacy. Moreover, they highlight tension between libertinism and redemption. His reported conversion gave moralists a lesson. Yet it also revealed his human struggle with mortality. Facing death, he may have sought reconciliation. Furthermore, his last days illustrate complexity—skeptic turned penitent. Whether true or not, the story endures. His conversion reflects cultural fascination with sin and salvation. Moreover, it complicates understanding of his philosophy. Audiences debate whether he remained libertine or embraced faith. His final days thus inspire both admiration and doubt. They complete his narrative of rebellion, decline, and resolution. Conversion, real or myth, underscores enduring fascination with Wilmot’s turbulent, brilliant life.

Posthumous Reputation

After his death, John Wilmot’s reputation continued to grow. His works circulated widely, admired and condemned alike. Moreover, he became legendary for wit and rebellion. His poetry inspired debate about morality, art, and freedom. Furthermore, posthumous interest highlighted enduring cultural relevance. Later readers saw him as both scandalous and genius. Romantic writers admired his candor and energy. Victorian critics condemned immorality yet recognized brilliance. Modern scholars celebrate his courage, wit, and artistry. Moreover, his reputation reflects changing attitudes toward freedom and satire. His works remain central to Restoration studies. Posthumous fame solidified his place in English literature. He stands alongside Dryden and Etherege as a Restoration icon. Yet his legacy feels distinct—more rebellious, more daring. His reputation proves the endurance of provocative voices. Through controversy, he remains alive in literary memory. His legend continues inspiring new generations.

Modern Reappraisal

Modern scholars reevaluate John Wilmot with fresh perspectives. They explore his wit, sexuality, and skepticism in cultural context. Moreover, critics see him as more than libertine scandal. His poetry reveals intellectual depth and philosophical struggle. Furthermore, modern reappraisal highlights his contribution to literary innovation. He challenged norms with honesty and creativity. Scholars examine intersections of satire, politics, and identity. Moreover, feminist and queer readings expand understanding of his work. His daring discussions of sexuality gain new relevance today. Contemporary critics value his boldness in confronting hypocrisy. They see enduring significance in his rebellion. Moreover, modern reappraisal positions him as both product and critic of Restoration culture. He becomes voice of courage, wit, and vulnerability. Such perspectives ensure his continued study. Modern interest reaffirms his importance. Through new lenses, Wilmot’s brilliance shines brighter. His legacy grows richer with each reinterpretation.

Lasting Legacy

John Wilmot’s lasting legacy lies in his fearless satire, libertine philosophy, and intellectual rebellion. His works challenged authority and celebrated honesty. Moreover, he embodied contradictions of Restoration culture—wit and vice, brilliance and decline. His poetry remains both scandalous and admired. Furthermore, his defiance inspired later generations of writers. He proved literature could confront society with wit and courage. His legacy extends beyond Restoration to broader questions of freedom. Moreover, his works remind readers of human struggles—desire, faith, mortality, rebellion. He remains symbol of daring inquiry. His impact lives on in classrooms, debates, and cultural memory. Moreover, his name evokes wit, provocation, and brilliance. John Wilmot continues to inspire as poet of rebellion and honesty. His lasting legacy confirms his central place in English literature. He remains enduring figure of Restoration wit, satire, and daring.

William Congreve Restoration Dramatist: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/06/28/william-congreve-restoration-dramatist/

Ernest Hemingway: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/ernest-hemingway-as-a-modern-american-writer/

Sir Alexander Fleming by Patrick Pringle: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/06/02/alexander-fleming/

Inferred Meanings with Examples and Kinds Explained:

https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/inferred-meaning-and-examples/

For more educational resources and study material, visit Ilmkidunya. It offers guides, notes, and updates for students: https://www.ilmkidunya.com/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.