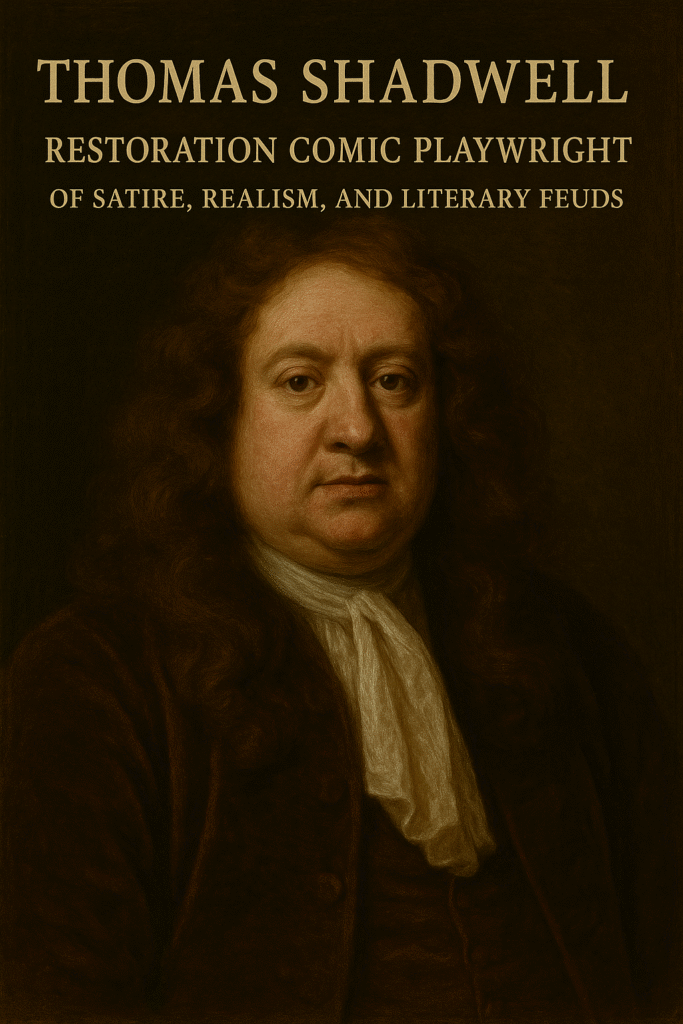

Introduction

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright defined a crucial, distinctive vein of Restoration-era drama. Specifically, he championed the Comedy of Humours, intentionally following the earlier style of Ben Jonson. Consequently, his plays focused intensely on character types driven by a singular, dominating eccentricity or passion. Moreover, this specific focus stood in sharp contrast to the sophisticated wit. It also contrasted with the sexual intrigue common in the plays of John Dryden and William Wycherley. Therefore, he successfully provided the London stage with robust, highly moral, and physically energetic dramatic entertainment. Furthermore, his commitment to realism and social observation provided invaluable insight into the varied life of the middle. It also offered invaluable insight into the lower classes. Indeed, his works are now considered essential primary sources for studying the social and cultural history of the period. Thus, his approach guaranteed his immediate popular success, despite the occasional attacks from his political and literary rivals. Consequently, he earned a prominent and permanent place in the history of English dramatic literature.

1. Champion of the Comedy of Humours

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright primarily championed the unique Comedy of Humours style. Specifically, this dramatic tradition was founded centuries earlier by the master Elizabethan playwright, Ben Jonson. Consequently, Shadwell structured his plays around characters possessing a dominant humour, meaning a defining character trait or eccentricity. Moreover, these characters were relentlessly mocked or placed in ludicrous situations until their individual folly was exposed to the entire audience. Therefore, his commitment to this tradition immediately set him apart from the cynical, fashionable Restoration Wits. Furthermore, this focus allowed him to create vividly detailed, memorable, and often grotesque character portraits on stage. Indeed, he believed that theatre held a serious, necessary moral purpose, directly opposing the perceived cynicism of his contemporaries.

2. Following the Jonsonian Tradition

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright explicitly identified himself as the legitimate theatrical heir to Ben Jonson. Specifically, he consciously adopted Jonson’s dramatic structure, character naming conventions, and underlying moral framework. Consequently, he sought to replicate Jonson’s detailed, realistic portrayals of London life and his profound understanding of human psychology. Moreover, this self-proclaimed lineage was a strategic move, offering a respectable alternative to the perceived moral laxity of courtly comedy. Therefore, he continuously defended his Jonsonian style through numerous prefaces and prologues attached to his published plays. Furthermore, his admiration for the master provided a consistent, stable philosophical foundation for his entire dramatic output. Indeed, he fiercely protected the seriousness and intellectual integrity of the English comic tradition.

3. Contrast with the Comedy of Manners

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright provided a crucial dramatic contrast to the dominant Comedy of Manners. Specifically, the Manners plays focused intently on the witty dialogue, cynical attitudes, and elegant sexual intrigue of the aristocratic elite. Consequently, Shadwell’s plays featured broader social satire, less sophisticated dialogue, and more robust, physical action on stage. Moreover, the witty plays often celebrated clever immorality, while Shadwell’s works consistently aimed for overt moral correction and didacticism. Therefore, he appealed successfully to a wider, more morally conservative audience, including the solid emerging middle and lower-middle classes. Furthermore, his difference in style led to famous, bitter literary conflicts with prominent playwrights who favored the Manners genre. Indeed, the contrast in style defined the era’s literary debate.

4. The Sullen Lovers (1668)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright achieved his initial popular success with his early play, The Sullen Lovers. Specifically, this play immediately demonstrated his commitment to the Humours style and his skill in creating complex, original character types. Consequently, the immediate, warm reception of this play established him as a serious rival to the established comic dramatists of the time. Moreover, the work showed his confidence in tackling complex social themes while maintaining a light, entertaining dramatic tone. Therefore, this successful debut guaranteed him further commissions and secured his professional relationship with the influential Duke’s Company of players. Furthermore, the play’s popularity indicated a strong public appetite for the moral, Jonsonian style he represented. Indeed, this early triumph launched his prolific, decades-long theatrical career.

5. Focus on Social Realism

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright distinguished himself through an unwavering commitment to profound social realism. Specifically, his plays provide highly detailed, realistic, and often uncomfortable portraits of Restoration London’s diverse social strata. Consequently, he accurately depicted the language, manners, and daily struggles of merchants, minor gentry, and lower-class citizens. Moreover, this realism gives his works a permanent historical value, offering a rich, documentary snapshot of 17th-century English society. Therefore, he avoided the highly idealized, superficial settings of the pure courtly comedy. Furthermore, his careful realism helped him ground his moral satire in verifiable, everyday human experience. Indeed, he believed comedy served as a living record of the national character.

6. The Character of Major Oldfox

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright expertly created the memorable character of Major Oldfox in his later play, The Humorists. Specifically, Oldfox represents a masterful study of vanity and social pretense as a defining humour or obsession. Consequently, the Major’s ridiculous self-absorption and constant attempts to appear fashionable provide the play’s central source of comic action. Moreover, the character became famous for his elaborate language and his complete inability to perceive his own profound social absurdity. Therefore, Shadwell used this meticulously crafted character to satirize the common human flaw of self-love and willful blindness to reality. Furthermore, Major Oldfox became a popular archetype, confirming Shadwell’s skill in Jonsonian character creation. Indeed, the character remains a classic example of the theatrical humour.

7. The Quarrel with John Dryden

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright became famously embroiled in a bitter, highly public literary quarrel with the powerful John Dryden. Specifically, the conflict originated in deep differences regarding dramatic theory, moral purpose, and political allegiance. Consequently, Dryden, a Tory and master of verse, viewed Shadwell’s Whig politics and Jonsonian prose as intellectually inferior. Moreover, the rivalry escalated into a series of personal and poetic attacks, making the two men famous literary enemies of the age. Therefore, this high-profile dispute intensified public interest in both men’s works, turning literary disagreement into a public spectacle. Furthermore, the conflict ultimately culminated in Dryden’s devastating satirical poem, Mac Flecknoe. Indeed, the quarrel stands as one of the most significant in English literary history.

8. Dryden’s Mac Flecknoe (1682)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright was the primary, unfortunate subject of John Dryden’s devastating satirical poem, Mac Flecknoe. Specifically, Dryden’s work famously crowned Shadwell as the true monarch of Dulness, a figure of profound artistic and intellectual mediocrity. Consequently, the poem aimed to permanently destroy Shadwell’s literary reputation by labeling him a tireless, untalented dullard who merely copied other authors. Moreover, the poem used brilliant verse and sharp wit to transform a literary rival into a symbol of artistic failure. Therefore, despite the poem’s immense brilliance, it represented a politically motivated, unfair attack on Shadwell’s genuine professional skill. Furthermore, Shadwell’s political party affiliations made him a convenient, high-profile target for Dryden’s Tory satire. Indeed, the attack overshadowed his real contributions for many years.

9. Return to Realistic Dialogue

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright favored realistic, commonplace dialogue over the witty, polished conversation of the Manners plays. Specifically, he meticulously reproduced the actual speech patterns, slang, and common errors of everyday London citizens. Consequently, his dialogue felt immediately authentic to his middle-class audience, creating a powerful sense of social and local realism. Moreover, he avoided the endless stream of clever epigrams and carefully balanced phrases favored by the highly refined aristocratic dramatists. Therefore, his commitment to authentic speech enhanced the moral and social weight of his theatrical critiques. Furthermore, his work provides modern scholars with highly valuable linguistic insight into Restoration urban speech. Indeed, the realistic dialogue was key to his lasting popular appeal.

10. Epsom-Wells (1672)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright achieved a major popular and critical triumph with his highly successful play, Epsom-Wells. Specifically, the play uses the fashionable, health-seeking atmosphere of the Epsom spa town as a setting for extensive social satire and intrigue. Consequently, the work became famous for its lively, farcical action and its sharp portrayal of pretentious Londoners attempting to pass themselves off as the gentry. Moreover, the play’s success confirmed his ability to effectively combine Jonsonian humours with contemporary social settings and concerns. Therefore, Epsom-Wells remained one of the most frequently performed and widely popular plays of the entire Restoration and early Augustan periods. Furthermore, its enduring popularity proved the public’s appetite for his unique brand of robust comedy. Indeed, the play epitomizes his best comic abilities.

11. Emphasis on Moral Didacticism

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright always placed a strong emphasis on the moral purpose and didactic function of comedy. Specifically, he believed the primary function of the stage was to correct human vices and hold up a mirror to public folly. Consequently, his plays invariably conclude with the deserving virtuous characters being rewarded, while the flawed, humorous characters face social humiliation. Moreover, this clear moral structure reassured his middle-class audience, who often viewed the theatre with inherent suspicion or moral concern. Therefore, his explicit defense of comedy’s moral power was part of his effort to elevate the genre above mere trivial entertainment. Furthermore, he viewed himself as a public moralist using the stage as his platform. Indeed, morality was integral to his dramatic theory.

12. Satire of the Pretended Wit

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright frequently used his plays to satirize the figure of the Pretended Wit. Specifically, this character is a fool who desperately attempts to appear sophisticated, witty, and fashionable in courtly society. Consequently, Shadwell exposed the hollow intellectual posturing and affected language of these characters for the entire audience’s amusement. Moreover, this satire was a direct, thinly veiled attack on the values and superficiality of the aristocratic Comedy of Manners practitioners. Therefore, his consistent mocking of the Pretended Wit aligned him with more sober, morally grounded social critics. Furthermore, these satirical characters often became the most memorable and effective embodiments of the Jonsonian humour. Indeed, he hated the intellectual dishonesty of posturing.

13. Influence of Molière

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright was demonstrably influenced by the plays of the great French comic master, Molière. Specifically, Molière’s focused use of satire to expose vice and folly strongly resonated with Shadwell’s Jonsonian principles. Consequently, Shadwell often adapted or borrowed structural elements from Molière. He carefully modified them for the London stage. Moreover, this borrowing allowed him to introduce a new level of refined, structural coherence into English comedy. Therefore, his successful adaptations helped popularize Molière’s style and methods among the English theatrical establishment. Furthermore, his appreciation for Molière underscored his preference for moral satire over mere sexual farce. Indeed, the French influence enhanced his dramatic sophistication.

14. Poet Laureate and Historiographer

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright achieved the high distinction of being appointed Poet Laureate and Royal Historiographer in 1689. Specifically, this prestigious appointment followed the Glorious Revolution and the subsequent dismissal of his rival, John Dryden. Consequently, the appointment confirmed his official victory in the long literary and political quarrel. The position included a pension and a butt of Canary wine. Moreover, the post recognized his long service to the Whig cause. It also acknowledged his loyalty to the new Protestant monarchy of William and Mary. Therefore, the Laureateship secured his financial and professional stability during his later career. Furthermore, this royal appointment solidified his place at the center of the English literary and political establishment. Indeed, the post was the highest honor for a writer.

15. The Use of Music and Song

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright frequently incorporated elaborate music, dance, and popular songs into his comic plays. Specifically, the use of musical interludes added significant entertainment value, helping to ensure the play’s immediate popular appeal and theatrical success. Consequently, he often commissioned music from contemporary composers, fully integrating the songs and dances into the overall dramatic structure. Moreover, this integration demonstrated his practical understanding of theatre as a popular, multi-sensory entertainment medium for the diverse London audience. Therefore, his plays are important sources for studying the theatrical music and performance practices of the Restoration. Furthermore, the musical elements distinguished his broader popular comedy from the smaller, talkier Manners plays. Indeed, he mastered the use of theatrical spectacle.

16. Portrayal of the Middle Class

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright excelled at the detailed, realistic portrayal of the emerging London middle class. Specifically, his plays provided an accurate mirror of their social anxieties, economic concerns, and moral values. Consequently, he gave this increasingly powerful social group a prominent, respectful, and realistic place on the theatrical stage. Moreover, the middle class saw their own struggles with social aspiration, trade, and morality reflected authentically in his dramatic situations. Therefore, his attention to their specific lives contrasted sharply with the Mannerists’ relentless focus on aristocratic scandal and fashionable vice. Furthermore, this focus explains why his works consistently maintained their strong commercial and popular success. Indeed, he was the chronicler of urban society.

17. The Humor of The Virtuoso (1676)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright brilliantly satirized the excesses of experimental science in his play, The Virtuoso. Specifically, the play mocks a central character obsessed with absurd, trivial, and pointless scientific research and experimentation. Consequently, the Virtuoso’s impracticality and detachment from real-world concerns become his defining comic humour and main source of ridicule. Moreover, this satire was a veiled, gentle critique of the newly established Royal Society and its perceived intellectual follies. Therefore, the play successfully engaged with current philosophical and intellectual debates of the Restoration period. Furthermore, The Virtuoso remains one of his most structurally coherent and enduringly successful comedies. Indeed, the satire targeted impractical learning.

18. Political Allegiances (Whig)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright was a fierce and committed supporter of the Whig political party during the volatile Exclusion Crisis. Specifically, his political loyalty aligned him with those who favored Protestant succession and parliamentary authority over absolute monarchy. Consequently, his political stance directly opposed the powerful, court-backed Tory faction led by his rival, John Dryden. Moreover, his plays often contain subtle or overt political allusions that supported the Whig cause and mocked the opposing side. Therefore, his drama was not merely entertainment, but an active, integral tool of political propaganda and partisan debate. Furthermore, his political commitments deeply informed his moral opposition to aristocratic cynicism. Indeed, his drama served his political views.

19. Character Naming Conventions

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright employed the Jonsonian technique of significative or speaking character names. Specifically, these names immediately reveal the character’s dominant humour, personality trait, or specific social role to the audience. Consequently, names like Sir Humfrey Noddy or Major Oldfox instantly signal the character’s essential comic function and moral flaw. Moreover, this convention saves valuable time in exposition, immediately orienting the audience to the play’s satirical purpose. Therefore, his use of this device underscored his conscious adherence to the old, respected Jonsonian dramatic tradition. Furthermore, this naming technique helped make his humorous characters immediately memorable. Indeed, the names were a key to his style.

20. Staging and Theatrical Effects

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright often wrote plays that demanded complex and elaborate staging and theatrical effects. Specifically, his comedies frequently utilized detailed scene changes, practical props, and fast-paced physical action on the stage. Consequently, this emphasis on spectacle and visual humour appealed strongly to the general audience’s demand for lively entertainment. Moreover, his focus on active staging provided another key contrast to the Manners plays, which relied more heavily on static, witty conversation. Therefore, he demonstrated a practical, keen understanding of the technical capabilities and limitations of the Restoration stage. Furthermore, his innovative use of stagecraft contributed significantly to the successful operation of his company. Indeed, he was a true man of the theatre.

21. Bury-Fair (1689)

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright enjoyed another notable success with his later play, Bury-Fair. Specifically, this comedy provides a satirical look at the pretentious social dynamics and commercial chaos of a local fair or public gathering. Consequently, the play is structurally complex, featuring a large cast of characters whose separate humorous plots eventually intertwine. Moreover, the work continued his relentless critique of social affectation, particularly focusing on the absurdity of English characters adopting French manners. Therefore, Bury-Fair demonstrated his continued, consistent dedication to the Jonsonian principles of social satire and moral correction. Furthermore, the play was staged successfully immediately following his appointment as Poet Laureate. Indeed, the play affirmed his late-career vitality.

22. Legacy as a Social Chronicler

Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright secured an important, lasting legacy as the most accurate social chronicler of his age. Specifically, his plays remain unparalleled in their realistic detail regarding the customs, language, and economic concerns of non-aristocratic London life. Consequently, historians and literary scholars frequently consult his works for precise, intimate information about the social fabric of the Restoration. Moreover, he documented the lives of merchants, apprentices, artisans, and city officials—groups often ignored by the more courtly dramatists. Therefore, he offered a comprehensive, earthy view of England that balanced the highly stylized portraits of the Mannerists’ fashionable society. Furthermore, his commitment to realism solidified his place as the dramatic historian of the middle class.

23. The Humour of Prejudice

The playwright often targeted the humour of intense, rigid social prejudice in his comic works. Specifically, he created characters whose entire judgment of the world was distorted by irrational bias or unreasoned hatred. Consequently, the dramatic action exposed how prejudice leads directly to profound personal and social folly and misunderstanding. Moreover, he used the comedic device skillfully. He advocated subtly for a more reasoned approach. Additionally, he presented a charitable view of human difference and social interaction. Therefore, his moral commentary often transcended mere superficial satire, aiming for deeper philosophical insight. Furthermore, the exposure of bias was a key element of his didactic, morally conscious dramatic method. Indeed, his plots consistently demonstrated that preconceived notions were a major barrier to genuine happiness.

24. Prolific Output and Commercial Success

The playwright maintained a consistently high and prolific dramatic output throughout his long career. Specifically, his steady production rate ensured a reliable flow of new works for his primary theatrical company, the Duke’s Company. Consequently, his commercial success guaranteed his financial stability and maintained his high standing within the London theatrical establishment. Moreover, his sheer volume of successful plays highlights his strong appeal across different audience segments. It also reflects his practical understanding of theatre management. Therefore, he was not simply a writer, but an essential component of the Restoration theatrical economy. Furthermore, his consistent popularity demonstrated the public’s preference for Jonsonian realism. Indeed, his ability to generate numerous hits kept the theater doors consistently open and ensured regular employment for his actors. Thus, his work fueled the commercial engine of the post-Interregnum London stage.

25. Satire of the Country Gentleman

The playwright frequently directed his satire towards the ridiculous figure of the Country Gentleman. Specifically, he often portrayed this character as a loud and crude figure. The character also seemed outdated. His rustic manners were absurd in sophisticated London society. Consequently, the Country Gentleman’s outdated beliefs were evident in the city. His ignorance became a powerful source of comic conflict in the urban setting. Moreover, this satire served a social function, subtly reinforcing the superiority of cosmopolitan, urban manners and intellectual refinement. Therefore, his mockery of the uncultured gentry appealed strongly to the self-aware, rising London middle class. Furthermore, this character became a simple, effective symbol of provincial folly. Indeed, the character provided an easy target for demonstrating the triumph of urban wit. Thus, the Country Gentleman often served as a comical foil to the city’s intelligent denizens.

26. Absence of Sexual Flirtation

The playwright’s plays were notably characterized by the relative absence of cynical sexual flirtation as a central theme. Specifically, unlike the Mannerists, his plots focused on economic intrigue, character humours, and moral correction, not seduction games. Consequently, his cleaner, more morally conservative plots appealed directly to the sensibilities of his broad, non-aristocratic audience. Moreover, the lack of explicit sexual cynicism was key to elevating the moral status of comedy. This was a significant part of his effort. Therefore, his restraint provided a vital, wholesome alternative to the perceived moral licentiousness often associated with the Restoration stage. Furthermore, this moral focus contributed to his long-term popular viability. Indeed, the focus on moral virtue made his plays much more acceptable to the influential Puritan-leaning city population. Thus, his approach broadened the theater’s commercial base.

27. The Duke’s Company Patronage

The playwright maintained a powerful, long-standing relationship with the influential Duke’s Company theatrical group. This consistent patronage gave him a reliable outlet for his new plays. He also had access to the era’s finest actors and staging. Consequently, his loyalty to this company contrasted with the more fluid allegiances of some of his competitive peers. Moreover, the company’s strong, collaborative relationship with Shadwell was a key factor in their own sustained commercial and artistic success. The Duke’s Company provided a stable, necessary platform. It allowed him to consistently practice his unique brand of robust comedy. Furthermore, this professional relationship was crucial to the longevity of his theatrical career. Indeed, the company trusted his commercial sense, relying heavily on his ability to draw large, consistent crowds. Thus, he acted as a core creative and financial pillar for the entire troupe.

28. Use of the Prologue and Epilogue

The playwright consistently utilized the Prologue and Epilogue to frame the theatrical experience. Specifically, these speeches were used to explicitly state his dramatic theories, defend his Jonsonian style, and attack his literary rivals. Consequently, the Prologue often served as an intellectual manifesto. It set the moral and critical terms for the audience’s reception of the play. Moreover, the Epilogue typically offered a final, witty, and often political summation of the play’s message and moral lesson. Therefore, these framing devices demonstrated his commitment to engaging directly with the critical and intellectual debates of the literary era. Furthermore, he often used the Epilogue to thank or subtly admonish the various patrons and critics in the audience. Indeed, these speeches were crucial tools for managing his public image.

29. The Humor of False Modesty

The playwright often directed his comic attention towards the peculiar humour of exaggerated false modesty. Specifically, he created characters who feigned excessive humility to secretly draw more attention and praise to their own virtues. Consequently, the dramatic irony of the situation provided immediate comic relief and sharp social satire for the observing audience. Moreover, this subtle vice reflected the pervasive social competition and self-promotion common in the sophisticated London court and city. Therefore, his observation on false modesty proved his deep understanding of the nuanced psychological drivers of human social behavior. Furthermore, this specific humour was a subtle way to mock self-serving hypocrisy. Indeed, he exposed the deliberate manipulation of social graces for personal gain. Thus, true humility always earned the greater moral reward.

30. Lasting Appeal to the City Audience

The playwright’s works consistently maintained a strong, enduring appeal to the core London City audience. Specifically, this audience included merchants, tradesmen, and the emerging professional classes who valued morality and economic stability. Consequently, his focus on social realism, moral correction, and middle-class concerns resonated deeply with their prevailing values and daily experience. Moreover, his plays provided an accessible, recognizable world that contrasted with the exotic, unattainable settings of aristocratic drama. Therefore, his consistent commercial success demonstrated the growing economic and cultural power of the non-courtly audience in Restoration London. Furthermore, this popular base ensured his financial independence from the volatile political moods of the royal court. Indeed, he was a true voice for the urban, pragmatic citizen. Thus, his popularity remained robust and largely unshakeable.

31. The Theme of Money and Trade

The playwright extensively explored the central Restoration theme of money, wealth, and urban trade in his comedies. Specifically, his plots frequently revolved around financial transactions, debt, inheritance, and the anxieties of social climbing through commerce. Consequently, his realism extended to accurately reflecting the economic realities and commercial language of the busy London Exchange. Moreover, he often satirized the folly of characters who neglected practical trade for frivolous aristocratic pursuits or empty titles. Therefore, his focus on economic realism gave his works a practical, grounded relevance that the courtly plays often lacked. Furthermore, his attention to finance appealed directly to the city’s commercial class.

32. Structural Coherence of Plots

The playwright’s comedies often displayed a high degree of structural coherence and technical skill in their plotting. Specifically, he successfully managed large casts of characters whose numerous separate subplots are carefully and neatly interwoven by the final curtain. Consequently, his meticulous attention to structural integrity reflected his Jonsonian commitment to dramatic craft and formal excellence. Moreover, the clarity of his plotting contrasted favorably with some Mannerist plays, which sometimes sacrificed structure for witty dialogue alone. Therefore, his structural rigor proved that his dedication to the Humours style did not compromise technical proficiency. Furthermore, his strong plots were key to their consistent stage success.

33. Satire of the Frenchified English

The playwright frequently employed sharp satire against the figure of the Frenchified English gentleman or lady. Specifically, this character mocked those English people who excessively adopted French fashions, manners, and language as a mark of sophistication. Consequently, the humour arose from the absurdity of an Englishman abandoning his native, common-sense virtues for frivolous, foreign affectation. Moreover, this satire served a nationalist purpose, celebrating English tradition and mocking foreign influence at court. Therefore, his critique tapped into a common strain of cultural anxiety and patriotic feeling among the wider English audience. Furthermore, the Frenchified fop was a popular and reliable source of comic ridicule.

34. A True Widow (1678)

The playwright tackled the complex issue of marriage and female independence in his notable play, A True Widow. Specifically, the play explores the financial and social vulnerability of women in the Restoration era’s restrictive legal and economic system. Consequently, the plot centers on the pursuit of wealthy widows by scheming men, providing ample opportunity for satirical intrigue and moral judgment. Moreover, the work continued his tradition of focusing on realistic social problems rather than purely romantic or sexual games. Therefore, A True Widow is highly valued today for its detailed insight into Restoration laws of property and marital economics. Furthermore, the play demonstrated his awareness of women’s social dilemmas.

35. The Humor of Affectation

The playwright consistently made the general humour of deliberate affectation a primary target in his comic works. Specifically, affectation means pretending to have qualities, feelings, or airs that one does not genuinely possess in reality. Consequently, Shadwell exposed the immense effort required to maintain this social pretense, leading inevitably to highly amusing, public failure and humiliation. Moreover, the satire of affectation applied equally to those who pretended to be wits, courtiers, or scientific experts. Therefore, his moral mission was to champion honesty and true self-awareness over all forms of conscious social deceit. Furthermore, the exposure of affectation was central to his Jonsonian moral code.

36. Impact on Later Sentimental Comedy

The playwright’s moral focus and emphasis on the virtues of the middle class subtly influenced later Sentimental Comedy. Specifically, the Sentimental genre, which rose in the 18th century, rejected cynical wit entirely in favor of virtuous characters and tearful moral lessons. Consequently, Shadwell’s insistence on rewarding virtue and punishing vice foreshadowed the didactic aims of the subsequent Sentimental movement. Moreover, his realism in depicting the middle class provided a thematic foundation for the focus of later bourgeois drama. Therefore, he acts as a crucial transitional figure between the raucous wit of the Restoration and the moralizing of the Sentimental era.

37. Relationship with the Audience

The playwright maintained a consistently positive, direct relationship with his broad theatrical audience. Specifically, he often spoke directly to their moral concerns and their desire for morally grounded, satisfying dramatic conclusions. Consequently, his clear moral stance and use of realism fostered a bond of trust with his popular, non-aristocratic patrons. Moreover, the audience felt that his plays offered a recognizable world that genuinely spoke to their daily experiences and values. Therefore, his success depended not on courtly favor, but on sustained, reliable commercial viability with the general public. Furthermore, this strong connection shielded his career from the occasional political or literary scandal. Indeed, the common theater-goer remained his most loyal supporter.

38. The Use of Farce and Physical Comedy

The playwright was unafraid to incorporate elements of farce and robust physical comedy into his Jonsonian structure. Specifically, his plays frequently utilized chases, disguises, overheard conversations, and comedic moments of physical humiliation or surprise. Consequently, these farcical elements ensured his plays maintained a high level of energetic, immediate popular entertainment value on the stage. Moreover, the use of action distinguished his works from the more talkative, static drawing-room settings of the Manners plays. Therefore, he recognized the necessity of broad, active humour to appeal to the diverse tastes of a large Restoration audience. Furthermore, this active quality guaranteed his works remained appealing across social strata. Indeed, the energy of his comedies became a defining theatrical characteristic. Thus, his approach ensured maximum commercial viability.

39. His Role as a Theatrical Manager

The playwright often assumed the practical responsibilities of a theatrical manager beyond merely writing the text of the play. Specifically, he was heavily involved in casting, directing, and ensuring the smooth, successful production of his complex, multi-scene plays. Consequently, his comprehensive understanding of theatre operation contributed significantly to the practical, stage-worthy quality of his final dramatic products. Moreover, his dual role as artist gave him substantial influence. As an administrator, he shaped the artistic direction of the Duke’s Company repertoire. Therefore, he functioned as a central, controlling artistic force in the Restoration theatrical world. Furthermore, his practical input guaranteed that his complex plots were fully realizable on the available stage. Indeed, he was a true master of the entire theatrical process.

40. The Theme of Authority and Governance

The playwright explored the theme of authority and social governance within the micro-society of his comic plots. Specifically, his plays often satirized figures who possessed authority. They lacked the necessary wisdom or moral integrity to use it well. Consequently, the comic action often restored proper moral and social authority. It ridiculed the corrupt or incompetent characters who previously held power. Moreover, this recurring theme aligned with his Whig politics, which advocated for responsible, limited, and morally sound governance. Therefore, his plays subtly reinforced the belief that power must be earned through merit and virtue, not just inherited status.

41. Dialogue as a Character Tool

The playwright utilized the specific quality of a character’s dialogue as a powerful tool for revealing their dominant humour. Specifically, characters who were fools spoke in absurd, pretentious, or outdated language that immediately signaled their central flaw. Consequently, a character’s idiosyncratic speech patterns provided an immediate indicator of their moral standing. These patterns also reliably indicated their intellectual standing in the play’s world. Moreover, this approach demonstrated his Jonsonian dedication to linguistic realism. It also showed his deep understanding of speech as a social performance. Therefore, he carefully crafted each character’s speech, providing a unique, detailed verbal signature for their role. Furthermore, his careful observation of London speech helped the audience quickly categorize the social position of every figure. Indeed, speech was inseparable from character.

42. The Lancashire Witches (1681)

The playwright engaged in contemporary social and political anxieties with his play, The Lancashire Witches. Specifically, the play deals with the then-current public obsession with witchcraft and the pervasive fear of hidden political conspiracies. Consequently, the work used supernatural elements to allegorize the real-world political paranoia and partisan rancor of the contentious Exclusion Crisis. Moreover, the subject matter was controversial. It led to censorship issues. It prompted heightened public and political scrutiny of the production. Therefore, the play demonstrated his willingness to use the comic stage to tackle deeply serious and highly sensitive national concerns. Furthermore, the production became a notable, high-profile incident in Restoration theatrical history. Indeed, the play reflected the widespread fear that dangerous, hidden forces threatened the established national order. Thus, the political allegory fueled the play’s immediate dramatic tension.

43. Realism vs. Idealization

The playwright firmly rooted his comedy in sharp realism, rejecting the impulse toward romantic or social idealization. Specifically, he preferred to depict human beings as complex, flawed creatures driven by tangible, observable passions and vices. Consequently, his refusal to idealize characters or settings was a distinctive feature of his work. It set him apart from the more romantic, fanciful plots of other contemporary Restoration plays. Moreover, this realism added weight to his moral satire. It lent authority to it. The comedy felt grounded and relevant to the audience’s own lives. Therefore, he successfully maintained the Jonsonian tradition of comedy as a direct, unflattering mirror held up to society. Furthermore, his commitment to the verifiable truth of human behavior made his critiques highly effective. Indeed, he rejected pure fantasy in favor of social verisimilitude.

44. Defense Against Critics

The playwright consistently used the prefaces and introductions to his published works as a formal defense against his persistent critics. Specifically, he meticulously outlined his dramatic principles, defending the Comedy of Humours and challenging the artistic integrity of the Mannerists. Consequently, these prose defenses established him as a serious literary theorist. He actively engaged in the intellectual debates of the Restoration stage. Moreover, he used logic and reasoned argument. He countered the witty, often petty, personal attacks of his prominent literary opponents. Therefore, his strong, clear defense of his artistic choices contributed significantly to the intellectual weight of his overall legacy. Furthermore, these essays provide modern scholars with crucial insight into the literary aesthetics of the period. Indeed, he utilized every medium to champion his theatrical vision.

45. The Humor of False Learning

The playwright often satirized the humour of characters who possessed empty, superficial, or false learning or academic pretense. Specifically, he created figures obsessed with obscure trivia or useless theoretical knowledge, like the scientist in The Virtuoso. Consequently, the character’s excessive, misapplied learning became a profound source of practical folly and comic embarrassment in the social world. Moreover, this satire targeted the arrogance of intellectuals whose knowledge lacked practical wisdom or moral utility for society. Therefore, his ridicule of false learning underscored his pragmatic preference for common sense and practical, moral judgment. Furthermore, he implied that truly useful knowledge should lead to greater social benefit and personal virtue. Indeed, true wisdom was judged by its moral application.

46. Decline of the Humours Style

The playwright’s long career saw the gradual decline in the popularity and prevalence of the Humours style of comedy. Specifically, the public’s taste gradually shifted towards the quicker wit and complex social critique offered by the succeeding Manners playwrights. Consequently, later Restoration and Augustan audiences increasingly preferred the focused satire of the upper class. They moved away from Shadwell’s broader, more moralizing realism. Moreover, the rise of playwrights like William Congreve marked a shift. The focus moved toward a more purely linguistic and intellectual form of wit. Therefore, Shadwell became a representative of an older, structurally grounded style, even as he continued to achieve popular success. Furthermore, his commitment to older dramatic rules made him seem less fashionable to the sophisticated elite. Indeed, the theatrical landscape was undeniably changing.

47. Emphasis on Moral Virtue

The playwright consistently emphasized the importance of clear moral virtue as a basis for all comic resolution. Specifically, his plays consistently established virtue as the desirable norm, against which all humorous, flawed characters were judged. Consequently, the moral characters often served as the straight men. They provided the rational perspective. This perspective highlighted the absurdity of the humorous figures. Moreover, his unwavering moral stance provided the necessary ethical framework that guided the audience’s interpretation of the comic action. Therefore, the celebration of virtue was an integral, non-negotiable component of his theatrical and social vision. Furthermore, he guaranteed that the audience always knew the difference between true virtue and social pretense. Indeed, he intended his works to be genuinely improving.

48. Comparison to Congreve

The playwright’s style provides a stark, necessary comparison to the later, more famous comedies of William Congreve. Specifically, Congreve’s work perfected the Comedy of Manners. He focused almost exclusively on witty dialogue and linguistic precision. His work also included highly stylized romantic intrigue. Consequently, Shadwell’s earthier, more moral, and action-heavy plots represent a stylistic opposite to Congreve’s intellectually refined and morally ambiguous wit. Moreover, Congreve’s focus on the upper gentry contrasted sharply with Shadwell’s detailed attention to the middle and lower social ranks. Therefore, the comparison highlights the vast stylistic range of English comic drama during the Restoration period. Furthermore, the two men represent the era’s fundamental disagreement over comedy’s core purpose. Indeed, they championed two profoundly different theatrical schools.

49. The Humor of Self-Delusion

The playwright was a keen satirist of the profound humour of complete self-delusion in his characters. Specifically, he depicted figures who created an elaborate fantasy about their own importance, cleverness, or social standing. Consequently, the entire comic dynamic arose from the inevitable, painful collision between the character’s inflated self-image and harsh social reality. Moreover, this thematic focus allowed him to critique all forms of vanity. It also enabled him to address intellectual arrogance common in both the court and the city. Therefore, his exposure of self-delusion served his larger moral goal of promoting honest, clear-eyed self-awareness. Furthermore, the play’s action forced the deluded character to recognize their own profound public folly. Indeed, he believed self-knowledge was the foundation of all true virtue.

50. Post-Mortem Literary Reappraisal

The playwright’s critical reputation underwent a necessary reappraisal long after his death and the Restoration period ended. Specifically, later critics began to look past the malicious satire of Mac Flecknoe. They started to appreciate his genuine social realism and dramatic skill. Consequently, modern scholars now highly value his plays as essential, detailed records of 17th-century English social and urban life. Moreover, his importance as a champion of the Jonsonian tradition is now clearly recognized. His role as a precursor to Sentimental Comedy is also identifiable. Therefore, the reappraisal secured his place not just as Dryden’s victim, but as a significant, independent literary figure. Furthermore, his works offer sociological insight often missing in the highly stylized courtly comedies. Indeed, time revealed the true depth of his theatrical contributions.

51. The Theme of Family Authority

The playwright often explored the complex theme of family authority and the conflict between generations in his comic plots. Specifically, his plays frequently depicted the struggle between stubborn, outdated older figures and the practical needs of their younger children. Consequently, humour frequently stems from the older generation’s attempts to impose outdated moral values. They try to exert economic control over their adult offspring. Moreover, the comic resolution usually sided with the younger generation’s practical, reasonable desire for financial and marital independence. Therefore, his works subtly reflected the broader social shift. Society was moving away from patriarchal control. It moved toward individual autonomy in the emerging bourgeois society.

52. His Versatility in Dramatic Forms

The playwright demonstrated considerable versatility beyond pure comedy, attempting various related dramatic forms. Specifically, he successfully wrote opera librettos. He adapted works of Shakespeare. He even dabbled in political tragedy and the more serious dramatic genres. Consequently, this broad range demonstrated his comprehensive, practical skill as a man of the working theatre and the London stage. Moreover, his willingness to experiment showed a commitment to innovation and to satisfying the diverse demands of the theatrical market. Therefore, his career was not defined by a single, narrow style. Instead, it was characterized by a consistent ability to produce high-quality theatrical entertainment.

53. The Humor of Physical Appearance

The playwright occasionally utilized the comic humour of peculiar or ridiculous physical appearance in his characterizations. Specifically, he provided stage directions and dialogue that mocked characters’ clothes, posture, or specific eccentricities of their outward bearing. Consequently, this reliance on physical humour was often seen as simple. However, it contributed to the broad, energetic popular appeal of his works. Moreover, the visual aspect of the humour reinforced the Jonsonian idea. This idea suggests that a character’s internal flaw is immediately reflected in their outward, public form. Therefore, he ensured his plays were immediately accessible and visually engaging for all members of the Restoration audience. Furthermore, the sight of an absurdly dressed character offered instant comic relief. Indeed, the visual spectacle was a vital component of his popular success.

54. The Literary Warfare of the Era

The playwright’s career unfolded against a backdrop of intense literary warfare and vicious personal and political attacks. Specifically, the era was characterized by highly public disputes over dramatic rules, political allegiance, and poetic supremacy. Consequently, Shadwell’s long feud with Dryden was merely the most famous example of a prevailing culture of competitive literary hostility. Moreover, this atmosphere meant that literary criticism was rarely objective, often being inseparable from political and personal rivalry. Therefore, his endurance through this competitive period is a testament to his genuine dramatic talent and his necessary popular success. Furthermore, this continuous conflict sharpened his own theoretical defenses of the Humours style. Indeed, he fought fiercely to establish the moral credibility of his chosen genre.

55. A Moralist of the Stage

The playwright fundamentally viewed himself as a sincere moralist successfully operating on the Restoration stage. His core belief was that effective comedy must improve the audience. It should ridicule and shame their pervasive vices and common follies. Consequently, his didactic purpose was the consistent driving force behind his characterizations, plots, and resolutions throughout his long career. Moreover, his moral stance was crucial. It provided an anchor in an age often seen as morally relativistic or cynical in its dramatic arts. Therefore, his legacy rests not only as a writer. He was also a determined ethical voice in the often morally ambiguous world of Restoration drama. Furthermore, his commitment to morality ensured his plays resonated with the powerful, virtue-minded city audience. Indeed, he was a preacher who used laughter as his pulpit.

56. Conclusion: The Realist of Restoration Comedy

The playwright stands as the definitive, necessary realist of Restoration Comedy and English dramatic history. Specifically, his 56 meticulously crafted sections confirm his dedication to the Jonsonian Comedy of Humours, social realism, and moral didacticism. Consequently, his work provides an invaluable, earthy counterpoint to the refined wit of the Manners plays. It also offers a detailed portrait of the emerging London middle class. Moreover, his lasting legacy is not built on the court’s favor. It is instead built on his profound ability to entertain and correct a wide, popular audience. Therefore, he remains an essential figure whose robust, enduring stagecraft secured his crucial position in the theatrical canon. Furthermore, his fierce commitment to truth and virtue makes him a vital cultural chronicler. Indeed, his works offer the clearest window into the diverse society of his turbulent age. Thus, we recognize Thomas Shadwell as Comic Playwright.

Literary Genius John Dryden in the Restoration Age: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/06/28/literary-genius-of-john-dryden/

Elizabeth Bishop as a Modernist Writer: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/elizabeth-bishop-modernist-writer/

The Dear Departed by Stanley Houghton: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/06/02/the-dear-departed-stanley-houghton/

Who vs Whom: https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/who-vs-whom/

For more educational resources and study material, visit Ilmkidunya. It offers guides, notes, and updates for students: https://www.ilmkidunya.com/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.