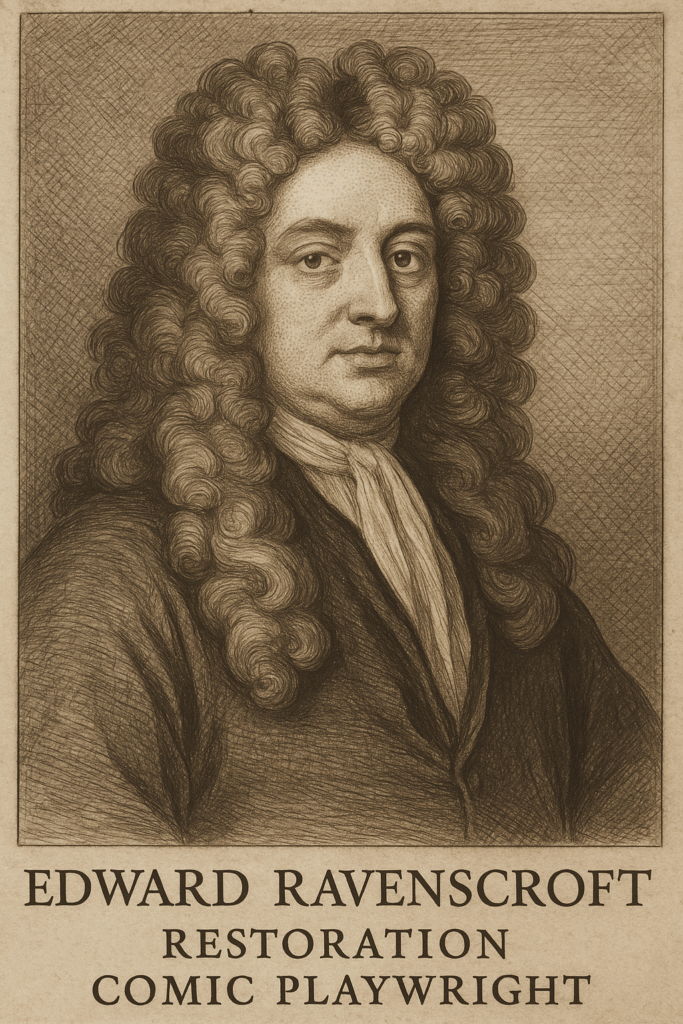

1. Introduction to Edward Ravenscroft’s Place in the Restoration

The Restoration period brought renewed energy to the English stage. Specifically, audiences enjoyed wit, satire, and commentary on society. Among the many dramatists of the era, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright established his own distinct style. Consequently, he combined clever humor with strategic adaptations, ensuring that his plays both entertained and provoked thought. Moreover, he often addressed larger themes about morality. He also explored hypocrisy and human weakness. Therefore, this balance allowed his productions to appeal to fashionable audiences while maintaining a sense of social critique. Furthermore, his reputation grew not only because of sharp dialogue but also because of his ability to craft engaging plots. Indeed, his career perfectly reflects the spirit of the Restoration theater itself—playful, daring, and critical. Thus, he gave audiences both laughter and profound reflection. Hence, his comedies helped shape how Restoration drama evolved across the late seventeenth century.

2. Early Life and Historical Context

The exact birth date of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright remains uncertain, but scholars place his early life in the mid-seventeenth century. Specifically, he came of age during a turbulent time in English history. Consequently, the Civil War, the Interregnum, and the subsequent Restoration all profoundly shaped the nation’s culture and politics. Moreover, by the time theaters officially reopened in 1660, there was an intense, strong appetite for witty, satirical plays. Therefore, audiences sought entertainment that actively pushed against earlier restrictions. Furthermore, writers like Ravenscroft found fertile ground for creative experimentation. Indeed, his career cannot be separated from this wider historical context. Thus, the Restoration was characterized by stark contrasts: libertinism versus morality, freedom versus authority, and indulgence versus restraint. Hence, these very tensions provided the perfect background for a comic dramatist to explore. Ultimately, his early experiences no doubt informed his later ability to critique society through biting humor.

3. Entry into the Theater World

The official reopening of the theaters in 1660 offered myriad opportunities to aspiring playwrights. Consequently, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright entered the scene at a moment when audiences keenly demanded novelty and sophistication. Specifically, London playhouses intensely competed to produce works that balanced genuine humor with clever, polished dialogue. Therefore, his first contributions gained critical recognition because they fully embraced the wit expected of the period while offering distinctive voices for unique characters. Moreover, success crucially required strong connections, and he likely cultivated relationships with key actors, theater managers, and influential fellow dramatists. Furthermore, the atmosphere was notably competitive, yet he managed to strategically secure his place. Indeed, he adapted earlier works for a new generation of audiences, a common and pragmatic practice that revealed his sharp awareness of market tastes. Thus, his entry demonstrated ambition, adaptability, and skill in recognizing precisely what Restoration audiences truly wanted.

4. Influence of Restoration Comedy Traditions

Restoration comedy operated on clear conventions, including sharp wit, sexual intrigue, satire of manners, and lively dialogue. Consequently, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright fully understood these traditions and employed them highly effectively. However, he also found innovative ways to subtly adapt and significantly expand them. Specifically, while some of his peers leaned heavily on scandal, he combined this with more structured, coherent storytelling. Moreover, his plays often exposed deep hypocrisy within fashionable society. Therefore, at the same time, he highlighted the folly of excessive pride and outright dishonesty. Furthermore, by working within existing conventions, he successfully secured immediate audience approval. Yet, his slight deviations from the norm showed genuine creativity, ensuring that his plays did not become overly predictable. Thus, this calculated balance between convention and innovation became a defining trait. Indeed, his work illustrates how Restoration dramatists could honor established expectations while still producing original entertainment.

5. Adaptation as a Defining Feature

One of the most distinctive and defining practices of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright was his commitment to adaptation. Specifically, he frequently reworked older theatrical plays, drawing especially from classical and continental sources. Consequently, this strategic approach allowed him to place familiar stories into entirely new contexts that perfectly suited Restoration sensibilities. Moreover, adaptation, in his hands, was not mere imitation; it required profound and creative transformation. Therefore, he injected a specific type of humor, wit, and topical references to make these stories resonate strongly with contemporary audiences. Furthermore, while critics sometimes accused him of lacking originality, his adaptations reveal a keen and sophisticated understanding of cultural translation. Indeed, he knew exactly how to reshape material for changing public tastes. Thus, his plays reveal the Restoration stage’s reliance on creative borrowing as an absolutely essential tool of dramatic production. Ultimately, he demonstrated both pragmatic skill and artistic boldness.

6. Style of Humor and Satire

The distinct humor of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright relied heavily on sharp dialogue, situational comedy, and deliberate exaggeration. Specifically, his biting satire consistently targeted vanity, profound hypocrisy, and foolish ambition. Consequently, unlike other writers who leaned entirely on sexual innuendo, he generally preferred broader, more accessible comedic strokes. Moreover, his characters often represented social types rather than nuanced individuals, making their flaws immediately recognizable. Therefore, audiences laughed not merely at the characters, but directly at the social realities reflected through them. Furthermore, his satire walked a fine and difficult line between pure entertainment and genuine critique. Indeed, it was biting enough to draw critical attention to human weakness yet playful enough to avoid completely alienating his audiences. Thus, this careful balance explains his enduring popularity. Ultimately, his laughter was never entirely empty—it always carried an underlying moral weight. Hence, his comedic style reveals his understanding of both audience expectations and the true power of satire.

7. Major Plays and Successes

Several key plays brought Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright widespread recognition, particularly The Careless Lovers and the notorious The London Cuckolds. Consequently, these successful comedies secured him a prominent and visible place within the dynamic Restoration stage world. Specifically, they skillfully combined energetic and complex plots with masterful comic exaggeration. Moreover, The London Cuckolds, in particular, became an immensely and frequently revived play, showing how much audiences genuinely enjoyed its theatrical energy. Therefore, his notable ability to craft entertaining situations and truly memorable characters kept his works alive on stage long after their initial debut. Furthermore, these successes demonstrated not only his dramatic talent but also his accurate ability to read the public taste. Indeed, his plays did not remain confined only to elite circles; they reached wider audiences, reflecting common social concerns. Thus, the endurance of his best works firmly confirms his role as a key and significant contributor to Restoration drama.

8. The London Cuckolds and Public Reaction

The London Cuckolds quickly became the single most notorious and enduring play of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright. Specifically, audiences found its raw, comic energy absolutely irresistible, and it remained a fixture in theatrical repertoires for many years. Consequently, the play intensely focused on contentious themes of jealousy, social deception, and marital discord. Moreover, its humor lay primarily in deliberately exaggerated situations and unforgettable, colorful characters. However, while audiences enjoyed the sheer laughter, some vocal critics complained openly about its perceived indecency. Nevertheless, the play’s undeniable popularity cannot be denied. Therefore, it effectively reflected both the strong public appetite for bawdy comedy and the underlying social anxieties about complex marital relations. Furthermore, its long life on stage clearly confirms Ravenscroft’s exceptional ability to create lasting, engaging entertainment. Ultimately, through this play, he reached a level of fame few of his contemporaries truly matched.

9. Responses from Critics and Rivals

Not all critical responses to Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright were entirely positive. Specifically, critics often accused him directly of plagiarism and over-reliance on simple adaptation. Consequently, rivals sometimes openly mocked his artistic methods, claiming he fundamentally lacked originality. However, such sharp accusations were notably common in the intensely competitive Restoration theater world, where creative borrowing was extremely widespread. Moreover, his critics reveal both the fiercely competitive atmosphere of the time and the challenge of effectively balancing adaptation with genuine creativity. Therefore, some fellow playwrights publicly dismissed his work, yet audiences consistently continued to enjoy his popular plays. Furthermore, this ongoing tension sharply highlights the divide between elite critical judgment and widespread popular reception. Indeed, his remarkable ability to maintain a strong stage presence despite harsh words proves his impressive resilience. Thus, criticism did not ultimately prevent his commercial success.

10. Ravenscroft and Political Commentary

Restoration drama often deeply engaged with clear political themes, and Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright proved to be no exception. Specifically, his comedies contained subtle but sharp reflections on authority, power, and the complex social hierarchy. Consequently, he strategically used humor to highlight various abuses and fundamental contradictions in political life. Moreover, satire allowed him to openly critique without necessarily defying official authority. Therefore, his plays effectively exposed the follies of those holding positions of power as well as the inherent weaknesses of ordinary citizens. Furthermore, in doing so, he skillfully linked private vices directly to public consequences. Indeed, political commentary in his plays may not have been direct propaganda, but it carried clear messages about governance and society. Thus, he reflected the acute anxieties of a nation still recovering from civil conflict and adjusting to new structures of monarchy and church. Ultimately, he understood that laughter could deliver sharp truths far more effectively than direct confrontation.

11. Ravenscroft’s Place Among Restoration Playwrights

Among his many peers, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright held a unique and distinct position. Specifically, he was not as daring as Wycherley nor as refined as Congreve, yet he skillfully carved out his own successful niche. Consequently, his notable reliance on adaptation both distinguished him and exposed him to criticism. However, his crucial ability to create highly enjoyable plays that audiences repeatedly returned to ensured his long-term relevance. Moreover, his reputation may not match the very greatest dramatists of the era, but he contributed significantly to the overall theatrical landscape. Therefore, he successfully provided works that bridged high wit and broadly accessible comedy. Furthermore, his plays formed an integral part of the collective body that ultimately defined Restoration theater. Indeed, without him, the stage would have notably lacked certain dimensions of popular humor and social critique. Thus, he proved that the Restoration stage genuinely needed both true innovators and skilled, pragmatic adapters.

12. Ravenscroft and Theatrical Performance

The long-term success of any single play depended profoundly not only on the written script but also on its vibrant performance. Consequently, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright consistently wrote with a keen awareness of specific stage dynamics. Specifically, his plots heavily relied on visual humor, precise timing, and lively, physical action. Therefore, this made his works particularly attractive to actors who relished energetic roles. Moreover, he also carefully considered direct audience reaction, often skillfully building suspense or laughter through meticulously arranged scenes. Furthermore, Restoration theater placed high value on spectacle, and he provided clear opportunities for both witty dialogue and engaging physical comedy. Indeed, performances brought his plays to life in ways that the written text alone could not fully capture. Thus, the lasting appeal of his works directly reflected their inherent adaptability to various performance needs. Ultimately, by writing with performance intently in mind, he ensured his plays endured not only as literature but as engaging, living entertainment.

13. Ravenscroft and Morality in Comedy

Comedy has always walked the fine line between pure entertainment and effective moral instruction. Consequently, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright leaned toward popular humor but did not consciously ignore underlying morality. Specifically, his plays revealed the profound dangers of excessive pride, greed, and moral dishonesty. Therefore, though his work was bawdy at times, it always carried underlying lessons about the inevitable consequences of human folly. Moreover, this crucial dual function allowed him to effectively appeal both to audiences seeking immediate laughter and to those expecting genuine ethical reflection. Furthermore, while Restoration comedy often purposefully blurred moral boundaries, his plays consistently showed an acute awareness of deeper social issues. Indeed, he demonstrated convincingly how laughter could teach as effectively as it could entertain. Thus, by presenting deliberately exaggerated flaws, he offered viewers a useful mirror of their own behavior. Ultimately, his approach proves that comedy in the Restoration was not simply frivolous but consistently carried the potential for moral insight.

14. Legacy of Adaptation and Innovation

Although his critical reputation faced significant challenges, the enduring legacy of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright lies in his unique approach to adaptation. Specifically, he convincingly showed how older literary works could find new, vibrant life on the Restoration stage. Consequently, by infusing these texts with contemporary wit and topicality, he created plays that spoke directly and powerfully to contemporary audiences. Moreover, his method vividly illustrates the profound creativity inherent in skillfully reworking existing material rather than simply inventing entirely from scratch. Therefore, later critics may have underestimated this unique skill, but it clearly reveals a sophisticated and pragmatic understanding of cultural translation. Furthermore, his adaptations highlight how theater essentially functions as an ongoing, crucial dialogue with past literary traditions. Indeed, without such necessary reimagining, the Restoration stage would have lacked much of its impressive variety. Thus, his legacy fundamentally demonstrates that adaptation can itself be a true form of innovation. Ultimately, his contributions continue to matter significantly in all discussions of Restoration theater.

15. Influence on Later Drama

Though later dramatists often surpassed him in critical fame, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright left subtle but noticeable traces on subsequent theater. Specifically, his consistent focus on adaptation inspired continued and vigorous debates about the nature of literary originality. Consequently, his commercial popularity showed convincingly that audiences valued immediate entertainment as much as literary refinement. Moreover, even if his plays gradually faded from the regular theatrical repertoire, they fundamentally influenced discussions about theatrical value. Therefore, later critics used him as a defining example in conversations about plagiarism, adaptation, and the limits of creativity. Furthermore, the simple fact that his works were successfully performed for decades indicates a real and undeniable impact. Indeed, while his direct influence may be subtle, his entire career embodies vital questions that remained central to all subsequent drama: what genuinely counts as original, what audiences truly desire, and how humor effectively shapes culture. Thus, in this important way, his artistic presence echoes clearly through later centuries of theatrical criticism and practice.

16. Ravenscroft in Literary History

Literary historians often carefully reassess figures like Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright to fully understand broader cultural dynamics. Specifically, he successfully represents the complex middle ground of Restoration drama—neither completely forgotten nor uncritically celebrated as a literary giant. Consequently, his popular plays reveal the true tastes of everyday audiences rather than only elite literary concerns. Moreover, historians value him precisely because he offers invaluable insight into what ordinary theatergoers genuinely enjoyed. Therefore, his comedies stand as clear evidence that Restoration culture was diverse, healthily embracing both sophistication and populism. Furthermore, while canonical writers primarily shaped literary theory, figures like Ravenscroft actively shaped the actual popular theater experience. Indeed, including him in the official literary history ensures a more complete and representative picture of the Restoration age. Thus, his plays may not stand alone as unquestioned masterpieces, but they provide absolutely essential context. Ultimately, he reminds us that literary history must always fully account for popular culture, not exclusively elite art.

17. Reception in Modern Criticism

Modern critics approach Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright significantly differently than his contemporaries did. Specifically, instead of simply dismissing him as derivative, modern scholars analyze his complex role within the theatrical culture. Consequently, they recognize his real contributions to understanding strategic adaptation, audience expectations, and the practical mechanics of comedy. Moreover, his plays are studied not only for their artistic merit but also for what they explicitly reveal about Restoration society. Therefore, the intense debates surrounding his originality acutely highlight ongoing questions about the nature of creativity. Furthermore, modern perspectives view him less as a failed genius and more as a truly significant cultural participant. Indeed, this critical shift allows for a much more balanced and comprehensive evaluation of his legacy. Thus, critical attention has naturally grown as literary studies expand to fully include non-canonical writers. Ultimately, his reception today acknowledges his flaws yet sincerely appreciates his lasting value. Hence, he remains important for what his career teaches about drama and the Restoration theater’s place in cultural history.

18. Ravenscroft and Audience Engagement

Restoration audiences were famously lively, highly vocal, and often unruly. Consequently, Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright needed to capture their attention both quickly and effectively. Specifically, he achieved this crucial goal by creating fast-paced, energetic plots and vivid, memorable characters. Therefore, he engaged viewers through a humor that was direct, accessible, and broadly appealing. Moreover, unlike some writers who aimed for refinement above all else, he always ensured his plays remained genuinely enjoyable to a broad social audience. Furthermore, this vital accessibility entirely explains his enduring popularity. Indeed, his works may not have satisfied every fastidious critic, but they consistently kept spectators intensely entertained. Thus, audience engagement was absolutely essential for theatrical success, and he indisputably mastered it. Ultimately, his plays encouraged shared laughter, immediate recognition, and social reflection. Hence, his ability to hold widespread attention reveals his practical, profound understanding of the theater.

19. Edward Ravenscroft and His Reputation

Edward Ravenscroft stands today as a playwright whose reputation mixes popularity with controversy. Specifically, he was celebrated by audiences yet often scorned by his rivals. Consequently, he clearly represented both the strengths and underlying tensions of Restoration comedy. Moreover, his reliance on strategic adaptation drew consistent criticism, but his plays demonstrably remained in active performance. Therefore, his name reminds us all that true theatrical success does not always directly match critical acclaim. Furthermore, he convincingly demonstrated how a working playwright could thrive by meeting audience expectations while still contributing meaningfully to literary culture. Indeed, his career clearly highlights the central role of adaptation, accessible humor, and moral commentary in Restoration drama. Thus, his reputation continues to spark academic debate, making him a fascinating figure for literary historians. Ultimately, whether praised or criticized, he holds a secure place in the narrative of seventeenth-century theater. Hence, he represents the lively, competitive, and inventive spirit of the age, ensuring his continued relevance.

20. Use of the French Source Material

Ravenscroft frequently drew on French theatrical works, particularly the comedies of Molière, as a primary source for his adaptations. Specifically, French drama, with its focus on structured plots and social satire, provided him with a robust framework for his own English comedies. Consequently, he often took the core dramatic structure from Molière but thoroughly anglicized the characters, wit, and topical references. Moreover, this practice was not unique, yet Ravenscroft’s skill lay in making the foreign plots feel immediately and deeply local. Therefore, his French adaptations allowed him to maintain a consistent output of new plays for the demanding Restoration stage. Furthermore, this strategic borrowing demonstrated his knowledge of continental trends and his practical approach to play production. Indeed, the French influence helped balance the bawdiness of purely English comedy with a more formalized, classical structure. Thus, his use of French material showcases his role as a crucial cultural translator.

21. The Importance of Plot Structure

Unlike some Restoration comedies that relied mainly on brilliant dialogue, Ravenscroft placed strong emphasis on clear, well-constructed plot structure. Specifically, his plays featured complex but tightly managed sequences of events, including numerous complications and highly timed revelations. Consequently, this reliance on plot mechanics ensured his comedies were lively, fast-paced, and highly effective for immediate theatrical performance. Moreover, the structured nature of his plots, often borrowed from foreign sources, gave his plays a sense of completeness and order. Therefore, while his dialogue was certainly witty, the audience’s engagement derived primarily from following the twists and turns of the unfolding action. Furthermore, his attention to structure helped maintain the comic energy over several acts, avoiding the narrative fatigue sometimes found in more dialogue-driven plays. Indeed, his structural discipline was essential to his commercial success. Thus, he was a master of the theatrical blueprint, prioritizing the engine of the story.

22. Collaboration with Actors and Companies

A significant factor in Ravenscroft’s long-term success was his practical ability to collaborate effectively with leading actors and theater companies. Specifically, Restoration theater was heavily actor-driven, requiring playwrights to tailor roles to the specific talents of star performers. Consequently, he developed strong working relationships with prominent players of the era, which guaranteed his plays priority in the production schedule. Moreover, his clear, action-oriented writing style made his plays a preferred choice for the busy Duke’s Company or the King’s Company. Therefore, his commercial viability stemmed directly from his understanding of the stage’s logistical and personnel requirements. Furthermore, successful collaboration ensured his works were performed to a high standard, enhancing their initial public reception. Indeed, his rapport with actors allowed him to refine his scripts based on genuine performance feedback. Thus, his career demonstrates the theatrical necessity of professional and social engagement.

23. The Theme of Financial Folly

A persistent and accessible theme throughout Ravenscroft’s comedies is the folly and consequences of poor financial management. Specifically, his plays often satirize the nouveau riche, highlighting their ignorance and their susceptibility to schemes and deceptions. Consequently, characters driven by greed, excessive ambition, or an ill-conceived desire for social status frequently become the primary targets of his comic ridicule. Moreover, this focus on money and social aspiration resonated powerfully with London’s growing merchant class, who formed a significant part of the theater audience. Therefore, the financial theme allowed him to explore the moral pitfalls of capitalism and the changing social hierarchy. Furthermore, his comedic resolutions often involved a form of poetic justice, where the financially foolish or greedy are punished or exposed. Indeed, the contrast between true gentility and acquired wealth provided rich material for his satire. Thus, the obsession with money drove many of the dramatic conflicts in his work.

24. Adaptation of Spanish Sources

Beyond French material, Ravenscroft also occasionally turned to Spanish dramatic sources, particularly the popular Comedia Nueva, for further inspiration. Specifically, Spanish comedies often featured intricate love plots, disguised identities, and a strong sense of honor, which he skillfully adapted for the English stage. Consequently, drawing from Spanish sources allowed him to introduce a greater sense of romantic intrigue and complexity to his plot lines. Moreover, this diverse borrowing ensured his repertoire remained fresh and prevented his work from becoming overly reliant on a single tradition. Therefore, his adaptations served as a kind of transatlantic theatrical exchange, bringing European dramatic forms to the London audience. Furthermore, the Spanish focus on elaborate plotting helped him maintain the structural discipline that characterized his most successful plays. Indeed, his versatility in handling different national styles was a testament to his practical skill. Thus, his Spanish adaptations illustrate his extensive reach for viable plot material.

25. Comparison with Wycherley and Etherege

Ravenscroft’s style stood in clear contrast to the sophisticated, cynical wit of earlier Restoration masters like William Wycherley and George Etherege. Specifically, while Wycherley offered dark satire and Etherege refined, almost anthropological comedy, Ravenscroft provided broader, more accessible humor. Consequently, he avoided the profound moral ambiguity that marks plays like The Country Wife, preferring clear comic resolutions and judgments. Moreover, his dialogue, though witty, was less dense and intellectually demanding than that of his major peers. Therefore, this difference in approach helped him capture a larger, less exclusively elite segment of the theatrical public. Furthermore, the comparison highlights the spectrum of Restoration comedy, demonstrating that popular success was not limited to the highest forms of artistic refinement. Indeed, his accessibility carved out a unique and profitable space in the competitive market, proving that popular taste valued clarity over cynicism. Thus, his success defined the middle ground of the genre.

26. The Role of Farce in His Comedies

Ravenscroft’s plays often incorporated elements of farce, relying on physical comedy, exaggerated situations, and swift, improbable plot turns. Specifically, this integration of farce ensured maximum audience laughter and contributed to the energetic, fast-paced nature of his productions. Consequently, unlike pure “comedy of manners,” which focused on verbal wit, his plays successfully balanced sharp dialogue with effective stage business. Moreover, the farcical elements were highly accessible, appealing directly to the groundlings and the less literary members of the audience. Therefore, this strategic inclusion helped broaden the commercial appeal of his work, guaranteeing consistent box office returns. Furthermore, the use of farce allowed him to push moral and social boundaries playfully without fully committing to serious satire. Indeed, he understood that a well-executed chase scene or visual gag could be as effective as a clever epigram. Thus, farce was a vital component of his practical theatrical arsenal.

27. Ravenscroft’s Female Characters

Ravenscroft’s female characters, while operating within the confines of Restoration morality, often displayed agency and sharp wit. Specifically, they were frequently instrumental in driving the plot, using their intelligence to expose male folly and hypocrisy. Consequently, women in his plays often acted as the moral center or the voice of reason against the chaotic behavior of the male protagonists. Moreover, in plays like The London Cuckolds, female deception becomes a necessary tool for survival or the pursuit of happiness. Therefore, although the plays usually ended with a return to conventional marital order, the path to that resolution was often paved by female initiative. Furthermore, his focus on moral outcomes meant that virtuous female characters were generally rewarded, aligning with the tastes of the more conservative segments of the audience. Indeed, his portrayal of women was pragmatic, reflecting both societal norms and theatrical necessity. Thus, his heroines were often cunning and capable, even within a patriarchal structure.

28. The Careless Lovers as a Benchmark

The Careless Lovers, one of Ravenscroft’s early successes, served as an important benchmark for his developing comic style. Specifically, this play demonstrated his ability to blend French-inspired plot structure with genuine English wit and social observation. Consequently, it established his reputation for lively, energetic comedy that promised audiences both amusement and a clear sense of social justice. Moreover, the play’s positive reception showed that audiences were ready for a comedy that was bawdy but not overwhelmingly cynical. Therefore, the template established in The Careless Lovers—structured plot, moralizing undertones, and engaging character types—guided his subsequent dramatic output. Furthermore, its success helped secure him the necessary patronage and theatrical connections needed to sustain a professional career. Indeed, the play was a declaration of his practical skill as a writer who could successfully balance critical demands with popular appeal. Thus, it remains a key work for understanding his evolution as a dramatist.

29. His Use of Topical References

Ravenscroft frequently enriched his plays with highly specific topical references to current London events, personalities, and social fads. Specifically, this technique ensured his comedies felt immediately contemporary and relevant to the audiences seated in the theater. Consequently, by referencing current events, he fostered a sense of shared, exclusive humor among the theatergoers who understood the local jokes. Moreover, the inclusion of topicality made his plays powerful mirrors of their immediate moment, enhancing their satirical edge. Therefore, while this strategy guaranteed initial success, it also meant that many of his less famous plays quickly lost their relevance for subsequent generations. Furthermore, his reliance on the present moment highlights the ephemeral, commercial nature of Restoration comedy as a popular art. Indeed, the use of rapid, fleeting references was a necessary tool for survival in the competitive London stage. Thus, his plays offer literary historians a valuable, detailed snapshot of everyday late-seventeenth-century life.

30. The Role of Prologues and Epilogues

The prologues and epilogues of Ravenscroft’s plays were crucial, functioning as direct communication with the audience and clarifying his dramatic intentions. Specifically, these segments, often delivered by star actors, introduced the themes and asked for the audience’s favor. Consequently, his epilogues frequently contained the sharpest moral or social commentary, summarizing the play’s lesson in witty, final couplets. Moreover, they allowed him to playfully respond to his critics or cleverly advertise his next theatrical venture. Therefore, the language of the prologues and epilogues was often different from the main body of the play, possessing a higher degree of direct political and literary engagement. Furthermore, these framing devices were essential for managing audience expectations and providing a final, controlled interpretation of the work. Indeed, they were a necessary convention for negotiating the often-unruly public space. Thus, these brief verses were powerful tools of commercial and critical control.

31. Ravenscroft’s Later Career and Output

Ravenscroft’s later career saw a slight shift in emphasis, but maintained his characteristic blend of adaptation and accessible comedy. Specifically, as tastes evolved, he continued to produce new plays, showing a remarkable resilience in the face of emerging dramatic styles. Consequently, his later works often engaged with the rising sensibility of ‘Sentimental Comedy,’ though still retaining his strong reliance on farcical elements. Moreover, his sustained output throughout the 1680s and 1690s is a testament to his tenacity and his continued theatrical viability. Therefore, while he never achieved the canonical status of the younger playwrights like Congreve, he remained a steady, working professional on the London stage. Furthermore, his consistent production schedule helped maintain his income and presence in the highly competitive theatrical market. Indeed, his later plays demonstrate his willingness to adapt his style to prolong his professional relevance. Thus, his longevity is a key part of his professional legacy.

32. The Use of Disguise and Deception

Disguise and deception are pervasive and fundamental plot engines in the comedies of Ravenscroft. Specifically, characters frequently adopt false identities or create elaborate ruses to pursue romantic goals or achieve financial advantage. Consequently, this reliance on mistaken identity often generates much of the situational humor and farcical complexity within his plays. Moreover, the use of deception allows him to explore the themes of social mask-wearing and the inherent hypocrisy of fashionable society. Therefore, the resolution of the play often involves the dramatic unmasking of the deceivers, leading to the restoration of social and marital order. Furthermore, this device was highly effective in a theatrical setting, relying on the audience’s privileged knowledge to heighten the comic tension. Indeed, the skillful management of multiple, interlocking deceptions showcases his mastery of comic plotting. Thus, disguise is essential for the comedic chaos that precedes his moral conclusions.

33. Ravenscroft and the City Audience

Ravenscroft enjoyed a particularly strong connection with the City Audience, composed primarily of London’s merchant and trade classes. Specifically, his plays often satirized the corruption of the court. They also mocked the pretensions of the nobility and appealed directly to this more commercially focused demographic. Consequently, his emphasis on financial folly resonated with the moral values of the bourgeois audience. Honesty eventually triumphed. Moreover, The London Cuckolds became a City favorite. His ability to tap into the anxieties and humor specific to this powerful social group was demonstrated. Therefore, his popularity with the City Audience ensured his financial stability and guaranteed reliable box office success. Furthermore, this broad appeal distinguished him from playwrights whose work was aimed almost exclusively at the cynical courtly elites. Indeed, his commercial success proves he was a playwright for a wide segment of the public. His work was not for a narrow group only. Thus, his work reflects the economic and cultural rise of the bourgeoisie.

34. The Theme of Marriage and Social Contract

Marriage and the social contract it represents are central thematic concerns in the comedies of Ravenscroft. Specifically, his plays explore the tensions between individual desire and the societal pressure for marital fidelity. Consequently, the comedies often feature characters who attempt to cheat or deceive their partners. The resolution invariably reaffirms the sanctity of the marital bond. The comedies often feature characters who attempt to cheat or deceive their partners. However, the resolution invariably reaffirms the sanctity of the marital bond. Moreover, this moral trajectory provided assurance to the audience that social stability would ultimately be maintained. Therefore, his treatment of marriage, though often bawdy, was fundamentally conservative in its ultimate message about order and responsibility. Furthermore, the plays function as a kind of cautionary tale, using humor to demonstrate the folly of breaking social agreements. Indeed, the restoration of order through correct marital alignment is a predictable and satisfying element of his dramatic formula. Thus, his comedies acted as social commentary on the most foundational of all human institutions.

35. Ravenscroft and the Printing of Plays

The printing and publication of Ravenscroft’s plays were an essential part of his commercial and literary success. Specifically, publishing his works allowed him to reach readers outside the theater, generating a secondary source of income. Consequently, the printed texts also fixed his literary claim to the adapted material and secured his legal copyright. Moreover, the popularity of plays like The London Cuckolds ensured that the printed editions sold well, demonstrating their wide cultural reach. Therefore, the publication of his works solidified his reputation beyond the ephemeral nature of the stage performance. Furthermore, the printed format allowed critics and rivals to scrutinize his methods, thereby fueling the very debates about adaptation and originality that kept his name in circulation. Indeed, the transition from the stage to the page was a crucial step in cementing his place in Restoration literary history. Thus, the printed texts of his comedies remain key documents for scholars today.

36. His Defense of Adaptation

Ravenscroft was aware of the constant criticism regarding his adaptations and often offered a spirited defense of his creative process. Specifically, he argued that adaptation required a sophisticated skill set, including cultural translation, plot refinement, and the successful application of contemporary wit. Consequently, he maintained that rewriting an older play for a modern audience was a creative act distinct from mere plagiarism. Moreover, he implicitly suggested that his method was necessary to sustain the rapidly consuming Restoration theatrical market. Therefore, his defense highlighted the practical realities of the stage, where a proven plot was often more commercially viable than a risky, entirely original one. Furthermore, this stance framed the debate as one between artistic idealism and necessary professional pragmatism. Indeed, his arguments contribute valuable insight into the working economics and cultural values of the Restoration literary scene. Thus, his defense of adaptation remains an important piece of Restoration critical writing.

37. The Use of Humors in His Characters

Ravenscroft frequently employed the comedic device of the Humors, drawing on the older tradition of Jonsonian comedy to create recognizable types. Specifically, his characters were often dominated by a single, exaggerated trait—such as jealousy, vanity, or covetousness—that governed their every action. Consequently, this reliance on the ‘Humors’ made the characters immediately accessible to the audience and heightened the farcical nature of the plots. Moreover, the comedic conflict in his plays often stemmed from the clash of these various, obsessive Humors. Therefore, by using these types, he was able to deliver clear moral judgments against specific vices without requiring deep psychological nuance. Furthermore, this technique created a sense of theatrical predictability, which was satisfying to an audience who preferred order and clarity in their comic resolutions. Indeed, the use of the ‘Humors’ connected his work to the English dramatic tradition while serving his own satirical ends. Thus, the ‘Humors’ provided a vital structural and moral component to his comedies.

38. Ravenscroft and Changing Theatrical Tastes

Ravenscroft’s long career spanned significant changes in Restoration theatrical tastes, requiring constant stylistic adjustment. Specifically, he successfully navigated the shift from the high-wit Comedy of Manners toward the more moralizing Sentimental Comedy of the late century. Consequently, his ability to incorporate elements of the newer, morally refined style while retaining his popular farcical core ensured his continued commercial viability. Moreover, his resilience stands in contrast to playwrights who were unable to adapt to the audience’s growing demand for more ethically sound entertainment. Therefore, his longevity demonstrates a pragmatic, market-driven approach to his craft, prioritizing public acceptance over strict artistic consistency. Furthermore, his career trajectory serves as a valuable case study in how a working dramatist survived the volatile and evolving demands of the London stage. Indeed, his willingness to update his formula proves his understanding of the theater as a living, breathing institution. Thus, he was a survivor of the changing theatrical landscape.

39. The Wrangling Lovers and Its Style

The Wrangling Lovers, another of Ravenscroft’s notable comedies, offers further insight into his distinct dramatic style. Specifically, the play is characterized by a high degree of energy, intricate plotting, and a clear focus on the dynamics of romantic conflict. Consequently, it showcases his skill in managing a large cast of characters whose romantic and financial interests are deeply intertwined. Moreover, the work relies heavily on the use of verbal sparring between the romantic leads, a hallmark of the Restoration’s obsession with witty dialogue. Therefore, the play successfully demonstrates his ability to write engaging romantic comedy that balances wit with a strong structural framework. Furthermore, the eventual resolution of the conflict reaffirms his commitment to a moral and orderly conclusion, where true love and virtue triumph. Indeed, The Wrangling Lovers is a prime example of how he blended romantic intrigue with his characteristic farcical flair. Thus, it confirms his versatility within the broader comic genre.

40. The Critical Debate on Literary Theft

The frequent accusations of literary theft against Ravenscroft fueled one of the most persistent critical debates of the Restoration era. Specifically, his numerous adaptations led critics to question the very boundaries between creative borrowing, legitimate adaptation, and outright plagiarism. Consequently, the controversy highlights the intense pressure on playwrights to produce new works rapidly for a demanding theatrical market. Moreover, Ravenscroft’s detractors argued that his method degraded the originality of the English stage. Therefore, his career became a lightning rod for the period’s anxieties about intellectual property and the value of sole invention. Furthermore, the debate shows that while borrowing was common, the sheer volume of his adaptations drew unique critical scrutiny. Indeed, the enduring nature of this debate proves that his methods challenged the emerging standards of literary ownership. Thus, the criticism ultimately solidified his reputation as the foremost adapter of the age.

41. Ravenscroft and the Rise of Sentimentality

As the 18th century approached, the theatrical climate saw the gradual rise of sentimentality, a movement Ravenscroft navigated with difficulty. Specifically, sentimentality favored pathos, refined virtue, and emotionally moving scenes over the bawdy humor and cynical satire of the earlier Restoration period. Consequently, while his later plays adopted some moralizing elements, they struggled to fully shed his reliance on overt farce and aggressive humor. Moreover, this stylistic tension meant his later works often felt awkwardly situated between the two opposing theatrical tastes. Therefore, the emergence of pure sentimental comedy eventually pushed his more boisterous style out of the dominant theatrical repertoire. Furthermore, his inability to entirely abandon his roots in Restoration license contributed to the decline of his popularity among the new, morally serious audiences. Indeed, his career serves as a transitional marker between the Restoration’s ribaldry and the 18th century’s moral earnestness. Thus, he represents a final stand for the older, lustier form of comedy.

42. The Theme of Social Mobility

The theme of social mobility, both achieved and attempted, is a central engine of conflict in many of Ravenscroft’s comedies. Specifically, he often satirizes characters, particularly those from the City, who strive to inappropriately adopt the manners and titles of the courtly elite. Consequently, this satirical focus on social climbing highlights the fluid, yet rigidly observed, hierarchy of late-seventeenth-century London society. Moreover, his plots often revolve around the exposure of these social pretensions, restoring individuals to their proper, assigned place. Therefore, the comic resolution, while humorous, implicitly reinforces the social order by punishing those who attempt to transgress established boundaries. Furthermore, this exploration of social status resonated strongly with both the established gentry and the ambitious merchant class. Indeed, the anxieties surrounding social change provided a rich and inexhaustible source of comedic material. Thus, his work offers keen insight into the social aspirations of the Restoration bourgeoisie.

43. Ravenscroft’s Historical Plays

In addition to his famous comedies, Ravenscroft also attempted to write historical plays, though these achieved much less lasting fame. Specifically, these non-comic ventures demonstrated his versatility but lacked the distinctive popular appeal of his successful comedies. Consequently, his historical works often followed established dramatic conventions. However, they failed to secure the widespread audience engagement that characterized his other productions. Moreover, his reputation was closely connected to the comic genre. As a result, audiences and critics struggled to take his serious works seriously. Therefore, his historical plays were not very successful. This underscores his greatest talent was in the practical application of farce and witty dialogue. Furthermore, his brief foray into a different genre showcases his ambition as a writer. He wanted to be recognized as more than just a successful comic dramatist. Indeed, while these plays are largely forgotten, they prove his willingness to explore the full range of theatrical forms. Thus, they remain a footnote to his overwhelming comic legacy.

44. Conclusion: A Pragmatic Dramatist

Edward Ravenscroft ultimately stands as a highly pragmatic and commercially successful dramatist of the Restoration stage. Specifically, his career was defined by his skillful adaptation, his keen understanding of popular taste, and his consistent delivery of accessible, energetic comedy. Consequently, while he may have lacked the singular genius of his canonical peers, his longevity and prolific output underscore his profound theatrical viability. Moreover, he bridged high wit with low farce, satisfying a broad spectrum of the London theatrical public. Therefore, his plays are crucial documents for understanding the tastes, moral concerns, and competitive economics of the late seventeenth-century theater world. Furthermore, his legacy lies in proving that adaptation, when skillfully executed, is a legitimate and necessary form of theatrical art. Indeed, the enduring controversy surrounding his originality only highlights his central importance in Restoration literary history. Thus, he remains essential to the complete narrative of English drama.

45. Conclusion: The Lasting Value of Ravenscroft

The legacy of Edward Ravenscroft as Comic Playwright cannot be measured solely by literary brilliance. Consequently, his true value lies in representing the practical, entertaining, and highly adaptive side of Restoration comedy. Specifically, he gave diverse audiences stories that effectively balanced immediate laughter with social critique, and spectacle with genuine insight. Moreover, his reputation as both a strategic adapter and a sharp satirist reflects much broader questions about creativity in Restoration drama. Therefore, though not always celebrated as a great innovator, he fundamentally shaped the theatrical experience for thousands of contemporary spectators. Furthermore, his comedies remain important for what they vividly reveal about Restoration society and its popular entertainment. Indeed, they demonstrably show how laughter could both entertain and successfully teach. Thus, his role shows that the Restoration theater thrived not only through singular geniuses but also through highly skillful craftsmen. Ultimately, the lasting value of his career lies in its ability to illuminate cultural tastes and practical theatrical practices.

Nahum Tate Restoration Poet Laureate: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/04/nahum-tate-restoration-poet-laureate-and-adapter/

Robert Frost as a Modernist Poet: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/robert-frost-as-a-modernist-poet/

Application for Remission of Fine: https://englishwithnaeemullahbutt.com/2025/05/20/application-remission-of-fine/

Inferred Meanings and Examples with Kinds:https://grammarpuzzlesolved.englishlitnotes.com/inferred-meaning-and-examples/

For English and American literature and grammar, visit Google: https://www.google.com

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.