Introduction: Why Structure Matters

The structure of Cleanness poem is deliberate, reflecting the work’s profound theological purpose. Moreover, the Pearl Poet carefully shapes each section to serve both moral and artistic goals. Consequently, every choice reinforces a deeper meaning, showing that form itself becomes a vehicle for teaching. Furthermore, the poem instructs through structure, as patterns guide readers toward ethical understanding. Sin, judgment, and purity appear in recurring cycles, and these cycles repeat with subtle variation to maintain engagement and clarity. Importantly, through such repetition, the poet emphasizes divine justice consistently. At the same time, structure highlights human error, creating contrast between heavenly order and moral failure. Additionally, transitions between episodes ensure coherence, linking cause and consequence. Ultimately, the structure of Cleanness poem merges narrative design with spiritual instruction, shaping both reader experience and moral comprehension effectively.

Structural Unity Through Themes

The poem relies heavily on thematic unity, which binds its structure together. At its core lie three biblical stories—Noah and the Flood, the destruction of Sodom, and Belshazzar’s feast. Each story reveals a fall from cleanness, followed by divine judgment. Although the settings and characters differ, the moral trajectory remains consistent. This deliberate repetition teaches readers to expect a clear spiritual pattern. First comes human sin, then divine warning, and finally, inevitable punishment. Because of this pattern, the poem gains cohesion. Moreover, the poet’s careful use of narrative symmetry deepens this sense of unity. Additionally, all three stories share a consistent tone. They shift from purity to corruption, from order to chaos. However, they do not end in ambiguity. Instead, each concludes with decisive divine action. This rhythm—purity, sin, judgment—gives the poem its spiritual momentum. Therefore, repetition becomes more than structure; it becomes the poem’s moral logic.

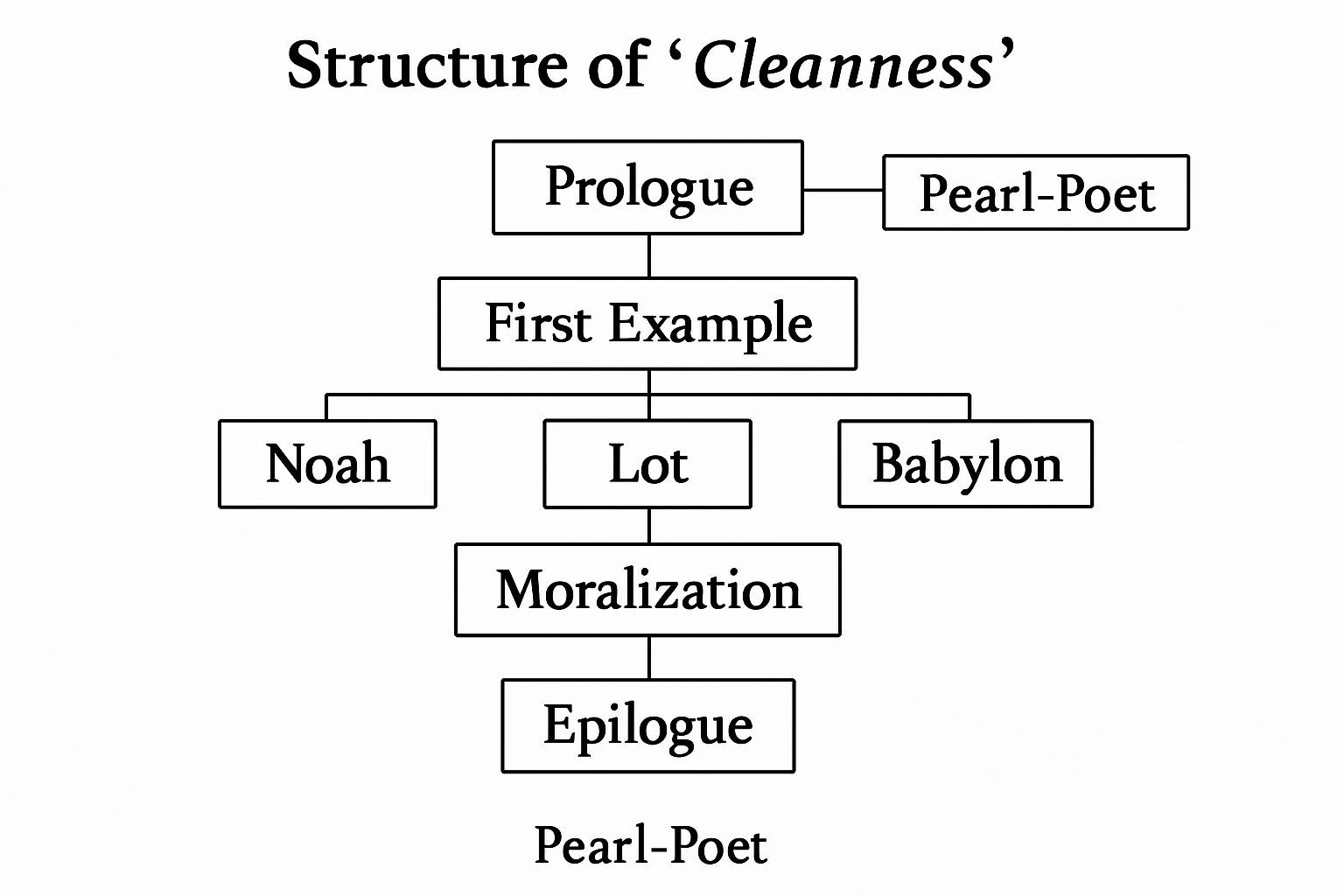

Tripartite Division: Three Major Examples

The structure of Cleanness poem is organized into three large narrative blocks, each conveying a clear moral lesson. These blocks include the stories of Noah and the Flood, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Belshazzar’s Feast. Moreover, every story follows a consistent pattern. A clean figure obeys God. An impure world rebels. Subsequently, punishment arrives. Consequently, this tripartite form reinforces ethical instruction and emphasizes divine justice. Additionally, repetition across the narratives ensures that lessons resonate deeply with readers, preventing moral understanding from being accidental or fleeting. Furthermore, transitions between episodes highlight the cause-and-effect relationship, linking human disobedience to divine correction. Importantly, the arrangement shows that justice is repeated, deliberate, and not random. Ultimately, the structure of Cleanness poem merges narrative design with moral purpose. It creates a cohesive framework. This framework guides readers consistently through sin, punishment, and restoration.

Symmetry as Moral Reinforcement

The structure of Cleanness poem includes a striking and deliberate symmetry that enhances its moral force. Specifically, the first and third stories—Noah’s Flood and Belshazzar’s Feast—depict widespread destruction on a grand scale. However, the middle story, the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, serves as a pivotal centerpiece. Because it connects and reflects both extremes, Sodom functions as a structural and thematic hinge. It echoes the themes of judgment from the flood while also anticipating the sacrilege of Belshazzar’s feast.

This central placement is not accidental. Rather, it adds both narrative and symbolic weight. Moreover, the order in which these stories appear is significant. It reflects a deeper theological pattern. Purity, in this structure, is always surrounded by acts of corruption. Likewise, obedience is placed beside rebellion to highlight moral choices. Therefore, the structure becomes more than organization—it becomes a visual and spiritual model of contrast between good and evil.

Parallel Scenes and Motifs

Throughout the poem, numerous scenes parallel one another, forming a deliberate network of repeating motifs. Wedding feasts, royal courts, divine interventions, and moments of judgment appear again and again. Because the poet crafts these recurring elements so carefully, each repetition builds upon the last. For instance, kings feast in both Noah’s time and Belshazzar’s court. However, only Noah shows obedience to God, while Belshazzar defies divine law. This contrast is no coincidence. Instead, it highlights moral divergence through structural alignment. Additionally, these parallels deepen the poem’s emotional and theological impact. They provide a framework in which one episode illuminates the meaning of another. As a result, attentive readers find new layers of significance in each scene. Mirrored events are not just artistic flourishes—they function as keys to interpretation. Therefore, structure becomes more than form; it becomes an active guide that interprets, expands, and clarifies the poem’s spiritual message.

Internal Patterning Within Each Tale

Each story within Cleanness possesses its own inner rhythm, carefully shaped to match its spiritual message. In the account of the flood, divine order emerges through Noah’s faithful obedience. In contrast, the tale of Sodom reveals how unchecked moral decay leads inevitably to destruction. Meanwhile, Belshazzar’s feast climaxes with the terrifying appearance of divine writing on the wall. This symbol of judgment cannot be ignored. Despite their differences, each narrative includes a righteous figure—Noah, Lot, or Daniel—who embodies cleanness and contrasts with the surrounding corruption. Furthermore, the poet structures each tale with a steady rise in tension. A sin is first introduced. Then, a divine warning is presented. Finally, punishment arrives, swift and certain. This escalating pattern not only creates dramatic suspense but also reinforces the poem’s central moral lesson. Because of this, the structure makes the consequences of disobedience vividly clear and emotionally powerful.

The Prologue and Epilogue Framing

Cleanness opens with a powerful general moral statement that sets the tone for everything that follows. The poet begins by praising the spiritual beauty of cleanness and condemning the moral filth of impurity. Because of this opening, readers are immediately placed within a world of divine values. The prologue does more than introduce the subject—it frames the purpose of the entire poem. It also prepares the reader to approach the following narratives not just as stories, but as moral exempla. Furthermore, the poet ends the poem in a similar fashion. After recounting the three major biblical episodes, he shifts once again to direct teaching. He no longer tells a story but delivers a sermon. Therefore, the structure of the poem moves from moral instruction to narrative and then back to moral instruction. This circular structure reinforces the message. The reader begins and ends in the presence of divine wisdom.

Repetitions that Educate

Repetition is a core structural device in the Cleanness poem, used with great purpose and precision. The poet intentionally repeats key phrases, dominant themes, and vivid imagery throughout the text. This repetition is never careless or excessive; rather, it serves as a method of emphasis. Because ideas appear multiple times, their importance becomes unmistakable. Repetition reinforces the poem’s rhythm while also guiding interpretation. Furthermore, it provides unity across different stories and scenes. For example, the words “clean” and “unclean” appear again and again. These terms are not mere descriptions—they carry deep theological weight. They anchor the entire moral message, reminding readers that purity is central to divine favor. The poet uses their recurrence to shape not only meaning but also memory. Therefore, the structure ensures that moral categories remain visible and constant. Through repetition, the poem engraves its lessons into both the form and the reader’s understanding.

Transition Devices within Structure

Each section of Cleanness moves smoothly into the next, reflecting the poet’s exceptional skill with transitions. Rather than abrupt breaks, the shifts between narratives feel intentional and fluid. The poet carefully links one tale to another, ensuring thematic and tonal continuity. He also varies the tone with precision, guiding the reader through changes in mood without disorientation. For instance, after recounting Noah’s story, the poet does not leap immediately into Sodom’s destruction. Instead, he inserts a reflective meditation on purity and divine favor. This interlude softens the transition and prepares the reader for the next moral crisis. Then, the narrative naturally flows into the downfall of Sodom. These transitions do not feel forced—they arise from the poem’s internal logic. Additionally, they reveal a deeply structured and contemplative mind at work. Therefore, transitions in Cleanness are not merely functional; they enhance the poem’s unity and reinforce its spiritual coherence.

Structured Verse and Alliteration

Beyond narrative shape, the structure of Cleanness poem also relies on poetic form, particularly its use of alliterative verse. This formal element is not decorative—it plays a crucial structural role. Each line is crafted with a careful balance of stressed syllables. Recurring consonant sounds add to this careful balance. Together, they create a steady musical rhythm. Because of this rhythm, the poem feels both lyrical and ordered. Furthermore, the alliterative sounds serve to highlight key words and reinforce central ideas. Repeated letters link phrases together, forming what may be called verbal chains. These chains not only enhance the auditory experience but also support thematic development. For example, the recurrence of similar sounds makes moral concepts easier to remember. Additionally, this technique binds the poem’s sections through consistent sonic texture. Therefore, sound itself becomes a form of structure. It serves as an organizing principle that matches the poet’s emphasis on divine harmony. It also aligns with the idea of spiritual clarity.

Digressions That Fit the Frame

At times, the poet digresses from the main narrative, shifting briefly into direct commentary or reflective interludes. However, these moments of departure are not chaotic or disruptive. Instead, they are woven skillfully into the overall structure of the poem. Because they serve a thematic purpose, they enhance rather than interrupt the moral flow. For instance, the poet includes a vivid description of courtly life, complete with rich clothing and regal ceremony. On the surface, this scene might seem unrelated to divine judgment. Yet it serves as a powerful contrast. It reveals how outward splendor can conceal deep moral decay. Additionally, these digressions remind the reader that corruption is present, not only in ancient times. It also appears in familiar, seemingly noble settings. These insertions feel natural because they align with the poem’s message. Therefore, even the poet’s detours contribute meaningfully to the structure and reinforce its spiritual objectives.

Temporal Structure: Past, Present, and Eternal

The poet also structures time with deliberate care, creating multiple layers that enrich the poem’s meaning. Firstly, the stories unfold in the biblical past, grounding events in sacred history. At the same time, the poet’s commentary speaks directly to the present, bridging temporal distance and engaging contemporary readers. Meanwhile, divine judgment exists in eternity, reminding audiences that God’s perspective transcends human time. Consequently, this three-layered temporal structure adds depth and complexity, connecting past, present, and eternal concerns. Furthermore, transitions between narrative layers ensure clarity, guiding readers through the shifting moments seamlessly. Importantly, this arrangement prompts reflection on personal conduct, as audiences must situate themselves within the moral timeline. Ultimately, the careful manipulation of time enhances both narrative and ethical instruction. It ensures that the poem communicates timeless spiritual truths while maintaining a compelling and coherent structure.

140-Word Paragraph: Noah’s Story as Structural Model

The story of Noah is more than a biblical tale. It becomes the poem’s structural model. The poet uses this narrative to establish rhythm. He begins with a divine decision. Sin on earth reaches its peak. Then Noah is chosen. He builds an ark, obeying God’s law exactly. The flood comes. Destruction follows. Afterward, peace returns. This arc—obedience, destruction, renewal—sets the tone for the rest of the poem. The stories of Sodom and Belshazzar follow similar paths. However, only Noah’s ends in peace. The contrast emphasizes human responsibility. Structure here reinforces moral vision. Moreover, the Noah story introduces key symbols. Water represents both cleansing and death. The ark symbolizes obedience. This pattern of symbolism is repeated in the other stories. Structure and imagery work together. This unity of parts reflects divine order. The poet builds structure not for beauty alone, but for belief.

Moral Geometry: Order as Theology

The poem’s structure mirrors its theology, demonstrating that God’s world has order, and therefore, poetry must reflect the same precision. Moreover, the Pearl Poet carefully shapes each verse so that every unit fits harmoniously into the larger design. Consequently, readers perceive a “moral geometry” that reflects divine logic and ethical balance. Additionally, the poem punishes disorder while praising righteousness, reinforcing the connection between action and consequence. Furthermore, transitions between episodes maintain clarity and coherence, guiding the audience through moral lessons effortlessly. Importantly, structure amplifies meaning, ensuring that narrative and doctrinal instruction work together seamlessly. By arranging stories and motifs deliberately, the poet highlights cause and effect, sin and redemption. Ultimately, the organization of the poem teaches as doctrine explains. It creates an integrated moral and aesthetic experience. This experience immerses readers in spiritual and ethical understanding.

Human Flaws in Contrast to Divine Order

The structure of Cleanness poem frequently contrasts human disorder with divine design, highlighting moral and spiritual lessons. Human actions often disrupt patterns, yet divine will restores them consistently. For instance, Belshazzar mocks sacred vessels, deliberately defying ritual order. Consequently, divine writing interrupts his feast, demonstrating that God enforces moral structure. Moreover, these contrasts emphasize the tension between human arrogance and heavenly authority. Additionally, the poem’s arrangement reinforces this lesson by alternating human misbehavior with divine intervention, creating a clear pattern for readers. Furthermore, transitions between episodes underscore cause and effect, linking disruption to correction. This deliberate contrast not only engages the audience but also teaches ethical responsibility. Human failure and divine order in the structure of Cleanness poem interplay. It ensures that moral truths remain central. It guides readers toward proper conduct and reverence for God’s design.

Cycles of Sin and Judgment

The structure of Cleanness poem relies on recurring cycles that guide moral understanding. First, sin emerges, inevitably leading to judgment. Subsequently, purity reappears, restoring divine order. These cycles repeat with variation, yet they always follow a consistent arc. Moreover, the repetition teaches that human history repeats moral failure unless corrected. At the same time, it demonstrates that hope returns through obedience and adherence to divine law. Additionally, the deliberate arrangement reinforces cause and effect, linking actions to consequences clearly. Furthermore, transitions between episodes highlight the connection between sin, punishment, and restoration. As a result, the structure serves both as warning and encouragement, emphasizing the necessity of moral vigilance. Ultimately, the poem’s cyclical design mirrors life itself. It shows that ethical patterns repeat. Redemption remains accessible through faith and discipline.

Didactic Purpose of Structural Pattern

The poem’s structure serves a clear teaching goal rather than mere decoration. Indeed, it is deliberately didactic, guiding readers toward moral understanding. By repeating patterns and motifs, the poet emphasizes eternal truth and spiritual order. Consequently, each story conveys the same lesson: cleanness matters. Moreover, the structure of Cleanness poem itself becomes the lesson, embedding ethics into form. Readers cannot escape this moral pattern, as every turn, example, and repetition reinforces divine guidance. Additionally, transitions between episodes create coherence, ensuring that each narrative connects logically to the next. Furthermore, the deliberate rhythm and repetition enhance comprehension, making the moral message unavoidable. Ultimately, structure shapes the reading experience, merging content and form to teach. The poem demonstrates that poetry can embody instruction, proving that ethical truths are inseparable from artistic design.

Structure Reinforces Symbolism

Symbolic elements in Cleanness gain power through deliberate design. For instance, feasts often represent human pride, and subsequently, destruction follows them. Consequently, this pattern repeats throughout the poem, emphasizing moral consequence. Moreover, objects and motifs reappear consistently. Water, vessels, food, and garments all recur, each gaining significance through repetition. Importantly, the structure of Cleanness poem reinforces these symbolic meanings, linking narrative form to ethical instruction. As a result, meaning deepens with each return, while patterns highlight divine order and human responsibility. Additionally, transitions between episodes ensure coherence and emphasize cause and effect. Furthermore, the poet’s careful arrangement strengthens interpretation, allowing symbols to resonate fully with readers. Ultimately, the structure transforms recurring elements into moral lessons. It proves that repetition and form work together to convey spiritual and ethical truths.

Conclusion: Structure as Sacred Form

In Cleanness, the structure is sacred and deliberate. Moreover, it mirrors divine logic, guiding readers toward moral understanding. The poet carefully repeats truth and punishes chaos, while simultaneously uplifting purity. Consequently, every line demonstrates intentional design, reflecting heavenly order. Importantly, the Pearl Poet uses structure to teach, not merely to entertain. Furthermore, the arrangement of tales, examples, and digressions reinforces spiritual lessons. The structure of Cleanness poem becomes a moral framework that shapes both thought and behavior. In addition, the interweaving of narrative and exempla ensures that readers grasp ethical principles fully. Transitioning between stories, the poem maintains rhythm and coherence, connecting human experience to divine will. Ultimately, the structure embodies the harmony between God’s plan and human responsibility. It proves that poetry mirrors life’s moral and spiritual architecture.

Human and Divine Contrast in Cleanness by the Pearl Poet: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/11/human-and-divine-contrast/

Don Delillo Postmodern Writer : https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/don-delillo-postmodern-writer/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.