Background and Context

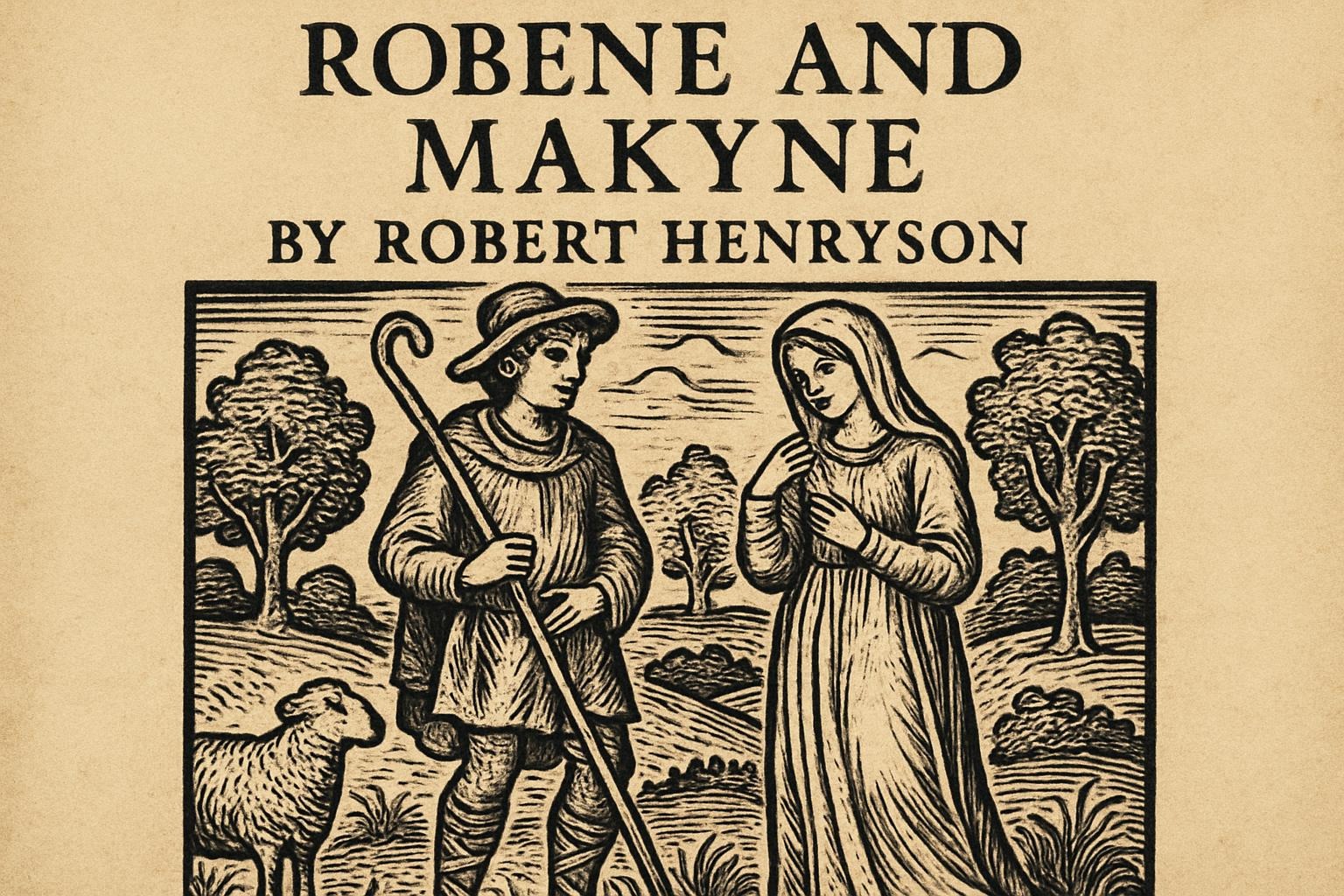

Robert Henryson, a fifteenth-century Scottish poet, is best known for his moral fables and refined narrative craftsmanship. Yet Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson reveals another side of his genius. He has a gift for natural dialogue and gentle irony. He also excels in rural realism. The poem belongs to his “shorter poems of stronger attribution,” preserved in Bannatyne Manuscript (1568). It reflects medieval Scotland’s pastoral culture, where shepherds and maidens represent both simple folk and universal human emotions. The setting appears rustic. However, Henryson’s intention is both moral and psychological. He uses love to mirror timing, opportunity, and regret.

Characters in the Story

In Robene and Makyne, Robert Henryson creates two memorable figures who embody both the simplicity of rural life and the complexity of human emotion. Though the poem appears short and straightforward, its characters — Robene and Makyne — reveal deep psychological insight and subtle moral meaning. Each line of dialogue between them uncovers shifting feelings of love, pride, desire, and regret. Through their exchange, Henryson captures the essence of human misjudgment and emotional transformation. The simplicity of the characters’ speech belies the depth of their inner worlds, making them among the most vividly human figures in medieval Scottish poetry.

Makyne: The Voice of Emotional Honesty

Makyne is the emotional center of Robene and Makyne. She initiates the dialogue with open affection, expressing her feelings for Robene without disguise or hesitation. Her words are direct, unembellished, and sincere. She represents the courage of emotional honesty, standing in contrast to Robene’s hesitation and emotional blindness. In the poem’s opening, Makyne’s love appears pure and steadfast, driven not by desire for reward but by genuine affection. Her character shows the strength of vulnerability — the willingness to expose the heart’s truth regardless of consequence.

Yet Henryson does not present Makyne as merely sentimental or weak. When Robene mocks her confession and fails to reciprocate, Makyne’s tone gradually changes. Her openness gives way to dignity and restraint. Instead of pleading, she accepts his rejection and withdraws her affection with composure. This transformation marks one of the poem’s most striking psychological turns. Makyne evolves from lover to moral instructor, from emotional seeker to detached observer. Through her, Henryson explores the moral dimension of love — that affection, when scorned, can turn into wisdom and independence.

Makyne’s evolution is both emotional and philosophical. Initially driven by love, she later embodies patience and self-respect. Her refusal to rekindle affection once Robene realizes his mistake highlights the finality of emotional change. She becomes a symbol of moral constancy, teaching that love, once betrayed or ignored, cannot easily return. In this sense, she represents the moral heart of Robene and Makyne, revealing Henryson’s theme of timing and emotional consequence. Her firmness in the end scene does not convey bitterness. Instead, it reveals enlightenment. She has learned to detach herself from futile desire. She accepts the natural course of feeling.

Robene: The Symbol of Human Hesitation

Robene stands as Makyne’s emotional counterpart and moral opposite. He is the figure of indecision, pride, and belated realization. At the beginning of the poem, Robene dismisses Makyne’s confession with playful mockery, claiming disinterest and avoiding emotional responsibility. His refusal is not entirely cruel but thoughtless — a reflection of human blindness toward what truly matters. Henryson portrays him as a man who fails to recognize the value of love until it is too late. This delayed awareness defines his character and forms the poem’s central irony.

Robene’s initial rejection arises from a mix of immaturity and self-centeredness. He enjoys the flirtation but does not grasp its sincerity. He speaks lightly, unaware that his words will soon carry regret. His character thus mirrors a universal human flaw: the tendency to undervalue what is freely offered. When Makyne withdraws her affection, Robene begins to experience emotional awakening. The reversal of roles — where the indifferent becomes the seeker — exposes the moral order of the poem. Henryson uses Robene’s change of heart to show that realization without timing brings no redemption.

As Robene’s regret deepens, his dialogue shifts from playful to desperate. He recognizes his error and attempts to reclaim Makyne’s affection, but his repentance arrives too late. Makyne’s rejection of him in the end is not vengeful; rather, it reflects the moral truth that love’s opportunity, once lost, rarely returns. Robene’s character thus embodies moral irony — he learns through suffering what he once ignored through pride. His transformation, though tragic, gives the poem its emotional depth. Henryson’s portrayal of Robene shows deep psychological realism uncommon in medieval literature. Instead of divine punishment, Robene suffers from emotional consequence — a distinctly human kind of fate.

The Interplay Between the Two Characters

The dynamic between Robene and Makyne defines the structure and meaning of the poem. Henryson constructs the narrative as a series of emotional reversals: first, Makyne loves and Robene rejects; later, Robene loves and Makyne rejects. This mirror-like structure not only builds symmetry but also underscores the theme of timing and consequence. Each character’s transformation reflects the other’s earlier position, creating a balanced moral lesson without overt sermonizing. Their dialogue is not simply a conversation about love; it is a conversation about human nature itself — the rhythm of desire, pride, and regret.

The emotional exchange between the two also highlights gender dynamics in medieval society. Makyne’s initial boldness challenges traditional expectations of female modesty, while Robene’s passivity undermines typical masculine assertiveness. Henryson subtly inverts social norms to emphasize emotional truth over convention. In doing so, he presents both characters as complex individuals rather than symbolic types. Their speech, filled with emotional nuance, gives voice to both yearning and reflection, humor and melancholy. The realism of their dialogue makes them feel alive beyond their pastoral setting.

Symbolic and Moral Dimensions

Beyond their literal roles, Robene and Makyne carry symbolic meaning. They represent not just two lovers but two aspects of human experience — awareness and blindness, action and hesitation, wisdom and folly. Makyne’s clarity contrasts with Robene’s confusion, and through their interaction, Henryson illustrates the moral principle that opportunities must be recognized and seized in their proper time. This timeless truth extends beyond romantic love, touching every form of human relationship and decision.

The pastoral context of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson also deepens their symbolism. The rural setting, with its simplicity and natural cycles, mirrors the emotional process of growth, decay, and renewal. Robene’s late awakening reflects the natural law that seasons — like emotions — cannot be reversed once they have passed. In this way, Henryson turns a simple love exchange into a reflection on life’s temporality. The fields and flocks that surround the characters act as silent witnesses to their human folly and moral awakening.

Emotional Realism and Lasting Appeal

What makes the characters in Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson enduring is their emotional realism. They are not abstract figures but living embodiments of ordinary feelings. Their words echo with sincerity, humor, and sorrow. Readers can sympathize with both — with Makyne’s wounded pride and Robene’s belated remorse. This emotional balance gives the poem its universal appeal. Henryson’s ability to portray such depth in a brief pastoral exchange reveals his mastery of human psychology long before the psychological novel existed.

Ultimately, Robene and Makyne remain unforgettable not because of grand action or dramatic tragedy but because they reflect truthfully how people love, falter, and learn. Their story becomes a moral parable without losing its emotional charm. Through them, Henryson teaches that love’s wisdom lies in recognition and that every hesitation bears its silent cost. Therefore, Robene and Makyne continues to resonate as a timeless study of love, pride, and human understanding.

Summary of the Poem

Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson is a short Scottish pastoral poem. It is profoundly insightful and explores love, rejection, and emotional reversal. The poem uses simple but powerful dialogue. Beneath its rural charm lies deep psychological and moral reflection. The poem centers on two characters. Robene is a young shepherd. Makyne is a maiden. Their exchange of affection and indifference reveals the complexity of human relationships. It also shows the inevitability of regret. In just a few stanzas, Henryson creates emotional tension and moral clarity. The timing of love determines joy or sorrow.

The poem begins in a peaceful pastoral setting, where nature’s calm mirrors the serenity of ordinary life. Amid this tranquil scene, Makyne approaches Robene, expressing her love with rare honesty and openness. Her confession comes with no artifice or deceit; she lays bare her heart to him. She tells him that her love has grown beyond her control and that his indifference causes her deep pain. Henryson’s portrayal of Makyne in these lines captures a sincere and human vulnerability. Her willingness to express her affection defies the expectations of medieval courtly love, in which women often played passive roles. Instead, Makyne becomes the active pursuer, showing emotional courage that commands both respect and sympathy.

Robene’s response, however, stands in sharp contrast to Makyne’s sincerity. He reacts with mockery and teasing, dismissing her feelings as mere foolishness. His laughter is light, but its cruelty cuts deeply. Robene’s indifference springs not from malice but from immaturity — a blindness to the seriousness of love. He fails to understand that Makyne’s confession is not a game but a genuine plea for emotional connection. His pride and detachment reflect a common human failing: the inability to value what is freely offered. Through Robene, Henryson exposes the moral danger of emotional complacency — the assumption that love will always wait.

As the dialogue continues, Makyne realizes that her love will not be returned. Her tone shifts from tenderness to dignity. She does not beg or protest; instead, she withdraws gracefully, accepting the pain of rejection with quiet strength. Her final words in this section reflect both self-awareness and moral wisdom. She tells Robene that he may regret his decision one day, when love’s opportunity is gone. This prophecy, delivered without bitterness, foreshadows the poem’s reversal and establishes its moral foundation. Makyne’s departure leaves Robene untroubled at first, but the emotional balance of the poem soon begins to change.

As time passes, Robene begins to experience the absence of what he once dismissed. Without Makyne’s affection, his world grows empty. The playful shepherd now feels the weight of solitude. His laughter fades into longing, and his earlier arrogance transforms into regret. Henryson depicts this transformation with subtle psychological realism. Robene’s awakening does not come through divine intervention or punishment but through the natural consequence of emotional blindness. The joy he once took for granted now seems precious beyond recovery.

When Robene finally approaches Makyne to declare his love, the situation has completely reversed. He becomes the seeker, and she, the one who withdraws. Yet unlike his earlier teasing, Makyne’s refusal is not cruel. She listens but remains unmoved. Her emotions have changed, and her love has passed like a season that cannot return. Her words are firm but not harsh — they reveal acceptance rather than resentment. She tells Robene that she once offered him her heart, but since he rejected it, she has learned to live without him. This emotional closure reflects one of the poem’s central lessons: love depends on timing, and once that moment is lost, no amount of remorse can restore it.

This reversal gives Robene and Makyne its enduring power. The symmetry of emotional roles is evident. Makyne’s love is followed by Robene’s love. It mirrors the natural rhythm of cause and effect. The first half of the poem is filled with pursuit and rejection. The second half reverses these roles. This creates moral balance. Henryson uses this structure not merely as a narrative device but as a reflection of human experience. Love, he suggests, is bound by time and circumstance. When opportunity is ignored, it turns into regret.

Beneath the surface simplicity, the poem conveys rich emotional and moral undertones. The pastoral setting — with its shepherds, open fields, and rustic imagery — symbolizes innocence and harmony with nature. Yet Henryson contrasts this idyllic environment with the inner turbulence of love. The natural world continues in peace while human hearts struggle with longing and pride. This juxtaposition heightens the poem’s poignancy. Nature stands as a silent witness to human folly, unchanged by the joys or sorrows of its inhabitants.

Another remarkable quality of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson lies in its tone. Though it deals with heartbreak and missed opportunity, the poem does not become tragic in a conventional sense. Instead, it maintains a tone of gentle irony. The reader is invited to feel both sympathy and amusement — sympathy for the pain caused by misunderstanding, and amusement at the predictable folly of human behavior. Henryson’s skill lies in maintaining this delicate emotional balance. He neither condemns nor sentimentalizes his characters. Instead, he allows their words and actions to reveal the moral truth naturally.

The conclusion of the poem reinforces this moral lesson without moralizing overtly. Robene’s regret serves as silent punishment, and Makyne’s composure signifies growth and wisdom. There is no reconciliation, no dramatic reunion, only the quiet acceptance of emotional reality. The simplicity of the ending reflects the inevitability of life’s lessons. Henryson leaves the reader with a sense of completeness — the feeling that justice has been done through the natural order of emotion rather than divine decree.

Moreover, Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson transcends its medieval setting through its universal theme. Every generation experiences the tension between desire and delay, affection and pride, opportunity and regret. Henryson’s pastoral simplicity thus conceals timeless human insight. The poem shows that love, when genuine, requires courage and awareness. Those who hesitate or mock sincere affection risk losing it forever. Yet those who suffer rejection can also find wisdom and peace in acceptance.

Through its musical language, emotional precision, and moral subtlety, Robene and Makyne exemplifies Henryson’s poetic mastery. It stands apart from his fables and moral tales by focusing not on animals or allegories but on real human feeling. The dialogue-driven structure gives it dramatic immediacy, while the rural imagery roots it in the natural world. It is both a love story and a moral parable, both tender and ironic.

Ultimately, the poem’s summary reveals more than a story of two lovers. It presents a study of timing, pride, and emotional transformation. It teaches that every feeling, like every season, has its proper time. Once that time has passed, no song or sorrow can bring it back. Through Makyne’s strength and Robene’s regret, Henryson reminds readers of the fragile balance between affection and awareness. Therefore, Robene and Makyne remains one of the most moving and insightful pastoral poems of the fifteenth century — a work where human emotion, moral reflection, and poetic beauty meet in perfect harmony.

Major Themes of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Love and Reversal of Desire

The central theme of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson revolves around the shifting nature of love and desire. At the poem’s beginning, Makyne confesses her affection for Robene, expressing her wish for companionship and affection. Yet, Robene remains emotionally distant, responding with indifference to her longing. His reluctance highlights the imbalance of desire between man and woman, an element that drives the emotional rhythm of the poem. When time passes and Makyne withdraws her affection, the balance suddenly reverses. Robene then discovers passion only when it is too late. This reversal conveys the inevitability of missed opportunity and emotional blindness. In Robene and Makyne, Henryson transforms a simple pastoral dialogue into a psychological study of human timing and emotional awareness. The poem thus reveals that love thrives not only on sincerity but also on readiness and mutual response.

Time, Opportunity, and Regret

Time’s influence on emotion forms another essential theme. Throughout the poem, moments of decision determine happiness or regret. When Makyne opens her heart, Robene’s hesitation causes him to lose the right moment. Later, when he realizes her worth, that moment has vanished. This shift symbolizes how emotional understanding depends on timing as much as affection. Henryson uses this motif to portray moral insight: love demands attentiveness to time’s rhythm. Once lost, opportunities rarely return. Through this temporal theme, Henryson blends pastoral simplicity with moral gravity. His lesson extends beyond romance—it addresses human tendency to undervalue what seems secure until absence reveals its importance. The rustic setting enhances this moral contrast, grounding timeless truths in the simplicity of shepherd life. Readers witness how delay transforms affection into despair and how opportunity, once ignored, becomes the seed of remorse.

Moral Reflection on Human Nature

Moral reflection lies at the core of Henryson’s poetry, and Robene and Makyne illustrates his skill in merging narrative delight with ethical insight. Beneath the pastoral surface lies an allegory of moral choice. Makyne’s patience contrasts Robene’s carelessness, showing the virtue of honesty and the peril of emotional pride. Henryson’s moral tone never feels didactic; instead, it flows naturally from the dialogue’s rhythm. The poem warns against the complacency that love’s familiarity can breed. When affection receives indifference, it eventually withdraws, leaving regret. Thus, moral reflection emerges not from punishment but from emotional awakening. Henryson’s audience, familiar with medieval moral allegory, would recognize this undercurrent. Yet his treatment remains human, focusing on internal struggle rather than divine retribution. Love’s moral significance lies in learning humility and awareness before loss imposes understanding.

Pastoral Simplicity and Psychological Depth

Although the poem belongs to pastoral tradition, it surpasses convention through psychological realism. Henryson portrays shepherd life with simplicity—fields, flocks, and rustic speech—but beneath this rural surface, he constructs a complex study of emotion. The shepherd and maiden embody universal feelings: longing, rejection, pride, and regret. In Robene and Makyne, Henryson transforms simple pastoral exchange into a mirror of human psychology. His characters’ emotions unfold naturally, resembling real human dialogue rather than idealized love-play. The pastoral form allows him to explore profound truths within ordinary surroundings. Moreover, his balanced use of humor and sorrow deepens the realism. Makyne’s playful wit contrasts her inner pain, while Robene’s eventual desperation reflects emotional growth born of regret. Through this subtle blending of simplicity and introspection, Henryson creates a poem both graceful and profound, rooted in nature yet timeless in meaning.

Gender Roles and Emotional Awareness

Gender roles shape the dynamics of pursuit and rejection in Henryson’s pastoral world. Traditionally, men pursue while women resist; here, Henryson reverses that pattern. Makyne’s open confession challenges cultural norms, while Robene’s refusal represents masculine detachment. When their positions later invert, Henryson reveals emotional equality beneath social convention. Both suffer from pride and misjudgment. This reversal undermines gender stereotypes, showing that emotional blindness transcends sex. Makyne’s eventual decision to reject Robene empowers her character, turning her from vulnerable lover to independent figure. Henryson thus anticipates later Renaissance portrayals of self-aware women who define their worth through choice rather than dependence. The poem’s emotional structure exposes the fragility of human pride and the equality of suffering between man and woman.

Irony and Emotional Justice

Irony governs the poem’s conclusion. Robene, once indifferent, becomes desperate, while Makyne, once pleading, turns distant. This emotional inversion embodies poetic justice. Henryson’s irony remains gentle rather than cruel, inviting sympathy for both lovers. Readers sense the sorrow of realization arriving too late. The moral order restores balance, but without vengeance. Emotional justice replaces divine retribution, suggesting that love’s fairness lies in mutual awareness, not in punishment. Henryson’s subtle irony encourages introspection. Each reader feels both characters’ sorrow, recognizing that love’s failure arises from human misjudgment rather than fate. The poem closes not with tragedy but with quiet resignation—a moment of reflective understanding.

Nature as a Moral Backdrop

Henryson situates his lovers within the Scottish countryside, where nature mirrors emotion. The meadows, hills, and flocks frame human feeling with symbolic resonance. Spring’s vitality contrasts emotional coldness, while later imagery hints at the fading warmth of lost affection. The harmony between natural and emotional worlds reinforces the moral rhythm. Nature observes without intervention, reminding readers that time and change govern all things. In Robene and Makyne, landscape becomes silent witness to love’s evolution from innocence to regret. Through natural imagery, Henryson fuses human experience with the cycle of seasons, suggesting that love, like nature, flourishes only through harmony and attentiveness.

Emotional Honesty and Self-Realization

Self-realization marks the poem’s emotional climax. Robene’s awakening, though too late, reveals the pain of recognition. Makyne’s withdrawal demonstrates strength born from heartbreak. Together they embody the emotional journey from desire to understanding. Henryson’s message lies in honesty—recognizing one’s feelings before circumstance enforces regret. Emotional awareness, not possession, defines moral maturity. In medieval context, such reflection aligns with moral didacticism, yet Henryson’s approach remains personal rather than doctrinal. He portrays emotional truth as moral wisdom achieved through experience.

The Universality of the Pastoral Experience

Despite its Scottish dialect and rural setting, the poem transcends geography. The shepherds’ emotions resonate universally. Henryson captures the essence of love, pride, and timing that defines human life across cultures. Readers find themselves reflected in these simple characters, realizing that wisdom often arises through pain. This universality ensures the poem’s endurance in literary history. By merging humor, realism, and moral sensitivity, Henryson created a timeless exploration of love’s irony.

Poetic Structure and Style in Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction to Henryson’s Craftsmanship

Robert Henryson’s poetic craftsmanship in Robene and Makyne demonstrates remarkable structural discipline and aesthetic harmony. His command of rhythm, meter, and diction transforms a short pastoral dialogue into an enduring masterpiece. The poem follows the conventional structure of medieval ballad form, yet Henryson adapts it with sophistication. He uses musical cadence to reflect emotional tension, weaving simplicity with depth. Each stanza operates like a dialogue frame, alternating between Makyne’s appeal and Robene’s response. This alternating rhythm mirrors the emotional push and pull of unbalanced affection. Through this deliberate design, Henryson merges form and feeling into one expressive flow. His craftsmanship reveals that poetic structure serves not only beauty but emotional precision. In Robene and Makyne, every line contributes to both meaning and melody, preserving harmony between speech and sentiment.

Stanzaic Structure and Rhyme Scheme

Henryson employs a seven-line stanza known as the rhyme royal, a form often used by Chaucer and later Scottish poets. The rhyme scheme (ababbcc) grants the poem a musical symmetry suited to dialogue. This pattern enhances the conversational rhythm while maintaining lyrical continuity. Each stanza encapsulates a self-contained exchange, ensuring coherence within the unfolding emotional narrative. Henryson’s use of repetition and rhyme allows readers to anticipate emotional shifts, echoing musical response. The tight structural control lends unity to the poem’s tone, while enjambment softens transitions between thoughts. The measured pace prevents sentimentality, allowing Henryson’s moral insight to emerge naturally. Thus, his stanzaic design becomes a moral rhythm, guiding readers through the emotional pattern of pursuit, refusal, and reversal.

Musicality and Rhythm

Henryson’s sensitivity to musical rhythm reflects his understanding of oral poetic tradition. Medieval Scottish verse depended on musical quality to engage listeners. In Robene and Makyne, rhythm echoes the cadence of speech, creating a melodic flow between voices. Each stanza feels like a musical dialogue, alternating between tension and release. The alliteration of consonants and the balanced syllables enhance the sound’s natural melody. The poet’s craftsmanship transforms ordinary conversation into lyrical harmony. The rhythm also mirrors the poem’s emotional journey—from hope to rejection, from laughter to sorrow. Musicality thus embodies both form and feeling. Henryson’s fusion of melody and morality reflects his belief that poetry should instruct through beauty. The harmonious structure transforms moral reflection into aesthetic pleasure, ensuring that rhythm itself conveys emotion.

Diction and Tone

Henryson’s diction combines rustic simplicity with philosophical subtlety. He writes in Middle Scots, using regional speech to convey authenticity. The words of shepherds feel natural yet refined, reflecting both rural life and inner thought. The tone alternates between playful teasing and emotional gravity, revealing depth beneath simplicity. Henryson achieves this tonal balance through contrast: Makyne’s tender words encounter Robene’s blunt replies. Later, tone reverses when Robene adopts emotional language, and Makyne responds with cool detachment. This tonal modulation prevents monotony and sustains engagement. Henryson’s diction reflects moral realism—plain words expressing complex truths. The language carries humor and pain within the same breath, showing his command over contrast. His tone remains sympathetic yet detached, allowing readers to interpret emotional shifts with clarity.

Use of Dialogue as Structure

Dialogue forms the poem’s backbone. Unlike narrative-driven ballads, Robene and Makyne unfolds entirely through conversation. This structural choice reflects Henryson’s dramatic sensibility. The alternation of voices creates rhythm while revealing character psychology. Makyne’s voice, soft yet assertive, reflects emotional courage. Robene’s speech, direct and unembellished, shows his detachment. The spoken form transforms pastoral scenery into a stage for moral exploration. Henryson’s dialogue captures spontaneity without losing poetic order. Each reply advances both emotional and moral progression, creating dynamic tension within restraint. The dialogic structure reinforces the idea that understanding arises through exchange—yet misunderstanding can also emerge from speech. Thus, conversation itself becomes the poem’s metaphor for human interaction, communication, and emotional delay.

Symbolism of Form

Form in Henryson’s work always serves moral intention. The structural symmetry of Robene and Makyne symbolizes emotional balance restored through reversal. The stanzaic repetition mirrors the cyclical nature of love—approach, refusal, regret, and return. The poem’s beginning and ending form a perfect circle, representing closure through recognition. This circular structure underscores moral symmetry, showing how time heals through understanding rather than reconciliation. Henryson’s form thus enacts meaning; the poem ends where it began but with altered awareness. The design mirrors human experience, where growth arises through repetition and reflection. Form becomes moral architecture—every line, rhythm, and return reinforcing ethical insight.

Imagery and Figurative Patterns

Imagery in Robene and Makyne enhances tone and mood without burdening simplicity. Henryson employs natural imagery—sheep, meadows, and sunlight—to reflect emotion rather than decorate it. The pastoral symbols align with emotional states: blooming fields signify affection, while fading light implies regret. The imagery deepens meaning subtly, allowing readers to feel transformation without direct statement. Metaphor appears sparingly yet effectively. For instance, the change of season parallels emotional change, symbolizing the transience of love. The figurative economy demonstrates Henryson’s restraint. His imagery clarifies rather than obscures thought. Through precision and naturalism, he transforms simple pictures into carriers of universal truth. The pastoral imagery also strengthens musicality, as sound and vision unite to create emotional resonance.

Meter and Sound Devices

The poem’s iambic rhythm maintains gentle regularity, reflecting conversational flow. Henryson integrates sound devices—assonance, alliteration, and internal rhyme—to heighten musical charm. These sonic patterns underscore emotional shifts. When Makyne speaks with tenderness, soft vowel sounds dominate; when Robene grows defensive, sharp consonants prevail. The poet orchestrates sound as emotional punctuation, allowing readers to hear transformation. This use of sound reinforces tone and psychological development. The musical structure mirrors oral recitation, inviting audiences into emotional participation. Henryson’s mastery lies in balancing technical discipline with natural voice, ensuring that sound never overshadows sense.

Blending of Medieval and Humanist Elements

Henryson bridges medieval moralism and emerging Renaissance humanism. His poetic structure maintains medieval moral order, while his style embraces individual psychology. The disciplined stanzaic form reflects moral tradition; the conversational realism anticipates humanist introspection. In Robene and Makyne, Henryson transforms a moral exemplum into personal narrative. His balanced structure unites order and emotion, rule and freedom. This synthesis defines his unique poetic style—a harmony of ethical thought and emotional truth. Through structural grace and musical coherence, he turns a rustic tale into timeless art. Henryson’s technique reveals that poetic structure need not constrain feeling; rather, it refines and illuminates it.

Tone and Mood in Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction to Emotional Atmosphere

The emotional landscape of Robene and Makyne defines its enduring charm. Henryson’s mastery of tone and mood turns a simple pastoral exchange into a meditation on love’s timing and emotional transformation. Although brief in length, the poem shifts between humor, sorrow, and reflection with seamless grace. Its tone evolves naturally from light conversation to profound melancholy. The changing emotional temperature creates depth, mirroring the unpredictability of desire and regret. Therefore, the poem’s mood becomes the true medium of its message. Through tone, Henryson expresses the essence of human experience—hope followed by hesitation, longing succeeded by loss.

From Playfulness to Sincerity

At the poem’s beginning, tone carries a playful rhythm. Makyne approaches Robene with gentle teasing, her speech bright with affection. Their exchange feels like an innocent game where words substitute for feelings too tender to reveal. Yet beneath the humor lies vulnerability. Makyne’s playfulness masks real emotion, while Robene’s indifference hides uncertainty. As their dialogue progresses, this tone of lightheartedness darkens into sincerity. The poet’s gradual modulation mirrors emotional exposure. Consequently, laughter gives way to silence, and wit transforms into truth. Henryson’s tonal progression shows that love often begins in jest but ends in confession.

Tone of Irony and Reversal

Irony pervades the emotional core of the poem. The initial imbalance between Makyne’s affection and Robene’s detachment reverses entirely. Henryson builds this reversal through tonal shifts rather than plot events. Early irony appears gentle—Robene’s indifference feels almost humorous. Later, irony sharpens into tragedy as roles invert. Robene becomes the seeker, and Makyne the rejecter. This reversal deepens the mood from light irony to moral reflection. The poet uses tone as a moral instrument, transforming situational humor into ethical awareness. The irony never feels cruel; instead, it humbles both characters through emotional education.

Mood of Longing and Distance

The prevailing mood throughout Robene and Makyne remains one of longing. Even moments of humor carry an undertone of absence. The emotional distance between the lovers defines the poem’s rhythm. Makyne’s yearning shapes the opening stanzas, while Robene’s regret shadows the ending. Henryson uses pauses, repetition, and rhythmic restraint to evoke this sense of emotional distance. The mood oscillates between approach and withdrawal, reflecting the lovers’ inability to meet in time. This mood of distance represents not separation alone but the moral truth that opportunity once lost cannot be reclaimed.

Contrast Between Outer Calm and Inner Turmoil

Henryson’s tone maintains composure even when emotion deepens. The calm surface of the dialogue conceals the storm within. Makyne speaks with dignity despite rejection; Robene retains composure when pleading later. This restraint intensifies emotional impact. By avoiding overt drama, Henryson achieves quiet power. The outer calm reflects pastoral serenity, while the inner conflict mirrors universal human struggle. The tension between serenity and suffering defines the poem’s aesthetic beauty. Through contrast, the poet teaches that true emotion lies not in loud expression but in measured silence.

Use of Humor and Wit

Humor operates as both defense and revelation. In early stanzas, Makyne’s wit protects her from humiliation. She jokes about love’s simplicity, pretending detachment. Robene’s humor, however, reflects ignorance rather than wisdom. Henryson uses these comic tones to soften moral tension. The lightness of speech allows deeper truths to surface without bitterness. As the dialogue unfolds, humor fades, replaced by reflective irony. The poet’s controlled laughter turns to compassion, guiding the reader through emotional awakening. Humor thus becomes a bridge between innocence and insight, showing how laughter can conceal and reveal at once.

Transition Toward Melancholy

The poem’s emotional descent into melancholy occurs subtly. Henryson does not mark the transition with sudden despair. Instead, rhythm slows, diction softens, and tone acquires gravity. Robene’s change of heart introduces the melancholy phase. His speech grows tender, his words sincere, yet too late. The atmosphere thickens with emotional weight as realization dawns. This shift defines the poem’s pathos: understanding follows loss. Henryson’s transition from brightness to sorrow mirrors the natural course of human emotion. Melancholy here means maturity—recognition of time’s irreversible flow.

Mood of Regret and Reflection

Regret dominates the final tone. Robene’s newfound longing carries no anger, only quiet acceptance. The mood becomes meditative rather than mournful. Through his realization, the reader perceives the poem’s moral symmetry. The emotional pattern forms a circle: Makyne’s early desire echoes in Robene’s later grief. Henryson uses this mood of reflection to elevate pastoral simplicity into philosophical resonance. The poet’s restraint ensures that regret feels human, not theatrical. The closing lines invite contemplation, not pity. The reader senses reconciliation with time’s lessons rather than despair.

Tone of Moral Equilibrium

Although emotion fluctuates, Henryson maintains moral equilibrium. He judges neither character harshly. The tone remains balanced, suggesting that both lovers act according to human limitation. Makyne’s refusal is not cruelty but wisdom; Robene’s pursuit is not folly but recognition. The poem’s moral tone derives from this fairness. The poet views emotional error as part of learning, not condemnation. His detached sympathy gives the poem timeless dignity. Therefore, tone becomes an ethical stance—understanding instead of reproach. The emotional moderation preserves harmony even amid loss.

Symbolic Resonance of Tone and Mood

The tone and mood in Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson embody the poem’s moral structure. Their modulation from joy to sadness, from pursuit to reflection, mirrors the rhythm of human growth. Henryson turns pastoral dialogue into symbolic expression of emotional maturity. Tone acts as narrative movement; mood becomes moral outcome. Through subtle variations, the poet guides readers from laughter to wisdom. The emotional journey reflects nature’s cycles—spring turning to autumn, warmth fading into stillness. This natural progression strengthens the pastoral symbolism and completes the moral circle.

Concluding Reflection on Emotional Unity

In conclusion, Henryson’s mastery of tone and mood unites form, feeling, and philosophy. The poem’s emotional range—from playfulness to melancholy—reveals life’s essential rhythm. Each tonal shift marks a stage in the journey from innocence to insight. The mood of loss never overwhelms hope; rather, it deepens understanding. Through tonal control, Henryson shows that emotion, when expressed with measure, becomes enlightenment. Robene and Makyne endures because it transforms the pastoral moment into timeless reflection. Its tone carries both laughter and wisdom, ensuring that the beauty of sorrow remains gentle, complete, and human.

Language and Imagery in Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction to Henryson’s Poetic Expression

Robert Henryson’s poetic mastery emerges vividly in his use of language and imagery. His diction, though simple, carries philosophical depth. The poet does not rely on ornate expressions or courtly embellishments. Instead, he achieves beauty through clarity, rhythm, and tone. The language mirrors both the pastoral landscape and the emotional intricacy of human experience. In Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson, the linguistic craft reveals how everyday speech can convey universal emotions. The poem’s Scots dialect breathes life into the dialogue, making the verses sound natural and musical. Henryson’s subtle handling of rustic conversation transforms the setting into a reflective moral world. Through language, he shapes a living texture that binds simplicity to symbolism.

The Role of Scots Vernacular

Henryson’s choice to write in Scots vernacular is crucial. During the fifteenth century, Scots evolved as a literary medium capable of both elegance and honesty. The language of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson combines realism with lyricism. Its words evoke the countryside’s authenticity without losing poetic grace. Every line captures the rhythm of rural speech, yet it transcends mere imitation. The colloquial tone creates intimacy between speaker and listener. It allows emotional immediacy, so readers feel the characters’ joy, frustration, and irony. The vernacular form also situates the poem within Scotland’s linguistic identity, asserting cultural pride in native expression. Thus, Henryson demonstrates that moral depth can emerge through local idiom as powerfully as through classical rhetoric.

Dialogue as a Literary Device

The entire poem, Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson unfolds through dialogue, which becomes both structure and symbol. The exchange between Robene and Makyne reflects the rhythm of life, filled with pursuit, hesitation, and regret. Dialogue conveys not only emotion but also transformation. Initially, Makyne’s tone is soft and pleading, expressing desire and vulnerability. Robene’s speech, in contrast, is detached, practical, and dismissive. When their roles reverse, the change in diction reveals moral irony. Henryson’s dialogue thus becomes a mirror for inner movement. It replaces the need for narrative exposition, letting speech embody character and emotion. The poet’s conversational technique bridges folk realism and allegorical subtlety, allowing moral reflection to emerge through natural rhythm.

Symbolic Language of Pastoral Imagery

Pastoral imagery forms the poem’s core aesthetic. Fields, flocks, and forests surround the lovers, creating a world of innocence and rhythm. Nature’s imagery reflects the progression of emotion—lush at the beginning, fading into melancholy as the lovers part. Sheep symbolize simplicity and devotion, while the wood becomes a place of solitude and reflection. The pastoral elements are not mere decoration. They function symbolically to contrast constancy and transience. The landscape mirrors inner states: when Makyne loves, the world seems fertile; when she withdraws, it grows distant. Henryson fuses external imagery with moral meaning, turning nature into a moral participant rather than a backdrop.

Metaphor and Irony

Henryson’s use of metaphor deepens the poem’s resonance. Love is depicted as both a natural impulse and a moral trial. The dialogue’s metaphors link emotion to season, growth, and harvest. When Makyne loves Robene, her passion resembles spring’s awakening. When she turns away, emotional winter descends. Irony then strengthens the poem’s moral point: feelings that once flourished now fade because of misjudged timing. This balance between metaphor and irony creates a reflective tone. The reader perceives love as both gift and lesson. Through this structure, Henryson teaches that emotional wisdom requires awareness of time, chance, and change.

Musical Quality of Language

Henryson’s verse possesses musical rhythm that heightens its emotional appeal. The repetition of phrases, the alliteration of key words, and the smooth rhyming couplets create a melody that echoes folk songs. This musicality turns moral reflection into aesthetic pleasure. The alternating voices of Robene and Makyne resemble a lyrical duet, embodying harmony and dissonance together. The simplicity of form allows emotional truth to emerge clearly. Moreover, the cadence supports memory, making the moral lesson linger. Henryson’s music of speech shows his deep understanding of how sound can express feeling without exaggeration. His lyric rhythm transforms everyday dialogue into timeless melody.

Natural Imagery and Human Emotion

The poem’s nature imagery constantly parallels the characters’ emotional states. The changing landscape becomes an emotional map. When love blossoms, the hills and meadows appear bright and open. When rejection or regret arrives, imagery darkens with shadows and silence. Henryson uses weather, light, and sound to mirror the human soul. Such technique blends emotional psychology with visual detail. The pastoral world becomes symbolic of moral consciousness. Henryson thus achieves emotional universality through local imagery. He captures how external scenes express inner truths, allowing the reader to feel love, pride, and sorrow through natural metaphors.

Contrast and Balance in Imagery

Imagery of contrast strengthens the poem’s moral structure. Robene’s indifference contrasts Makyne’s intensity. Warmth alternates with coldness; fullness opposes emptiness. Henryson constructs balance between opposites to portray moral symmetry. The contrasting imagery of growth and decay symbolizes time’s irreversible motion. Once lost, opportunities cannot return to the same state. This visual duality creates harmony within irony, teaching that love’s perfection lies in right timing. The poet’s balanced imagery maintains unity even as the characters diverge. The pastoral setting, though gentle, hides this stern moral equilibrium beneath its simplicity.

Emotional Subtlety through Word Choice

Henryson’s diction reveals emotional gradation with precision. He selects words that carry both literal and connotative significance. Words like “saftly,” “luf,” and “tyme” express tenderness, desire, and fate. Through such vocabulary, emotion gains texture. The poet avoids exaggeration, preferring understatement that deepens feeling. The language’s emotional subtlety also reflects moral discipline—love must feel but not consume. Each word balances affection and restraint. In this harmony of tone, Henryson achieves maturity of expression unmatched in earlier Scottish poetry. His diction proves that emotional strength can exist within linguistic moderation and moral clarity.

Conclusion: Language as Moral Mirror

Henryson’s language and imagery form the moral soul of his art. Every phrase combines clarity with suggestion, realism with allegory. Through rural speech and vivid imagery, he elevates ordinary experience into reflective wisdom. His linguistic choices reveal human truth through natural beauty. The Scots dialect gives identity, rhythm, and sincerity, while imagery transforms moral insight into emotional experience. In this unity of language and vision, Henryson proves that poetry’s greatest strength lies not in ornament but in authenticity. The poetic voice in this work remains eternally human—tender, ironic, and wise.

Moral Interpretation of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction: The Moral Dimension of Pastoral Love

At its core, Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson is not a simple rustic love dialogue; it is a finely woven moral reflection on timing, pride, and human folly. Henryson uses a pastoral framework to explore how misplaced affection leads to spiritual imbalance. Beneath its humorous simplicity lies a profound moral message. The poem teaches that emotional wisdom depends on recognizing the proper moment for love and truth. It also exposes how delay, hesitation, or reversal can destroy the harmony of affection. Through the lovers’ shifting fortunes, Henryson turns an innocent pastoral scene into a moral allegory of human imperfection and divine justice.

Love and the Consequences of Misjudgment

The central moral of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson lies in the misjudgment of love’s timing. Makyne’s early affection and Robene’s cold response represent moral blindness on both sides. She offers sincere emotion at a moment when he fails to value it. Later, when he finally awakens to love, she rejects him with equal firmness. This reversal teaches the consequence of emotional ignorance. Henryson shows that human desire often awakens too late, when the chance for connection has already passed. The moral lesson echoes medieval Christian values that time, once lost, cannot return. The failure to act rightly within the appointed moment becomes both emotional and moral error.

The Reversal as Moral Justice

The reversal of roles between Robene and Makyne serves as poetic justice. In the beginning, Robene’s pride blinds him to love’s sincerity. Later, he experiences the same pain he once inflicted. Henryson presents this turn not merely as irony but as moral equilibrium. The poem suggests that every emotional action invites a corresponding consequence. Thus, moral order is maintained through reversal. Makyne’s refusal restores balance to a world momentarily distorted by indifference. Through this symmetry, Henryson portrays divine justice operating quietly within human experience. The pastoral tone softens the lesson, yet the underlying moral structure remains sharp and unmistakable.

Timing as a Moral Principle

Time governs the entire moral logic of the poem. Henryson treats time not merely as sequence but as a divine measure of moral responsibility. The failure to love at the right time signifies spiritual blindness. In Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson, opportunity represents moral grace. Once rejected, it disappears permanently, symbolizing the fleeting nature of divine mercy. The poet thus connects emotional awareness with moral vigilance. Acting at the right time reflects not impulsiveness but harmony with moral truth. Through this perspective, love becomes a test of moral discipline—one must feel sincerely and respond wisely before time closes the door.

The Moral of Regret and Recognition

Regret forms another moral pillar of the poem. Robene’s belated realization mirrors humanity’s tendency to recognize truth only after loss. His sorrow is not punished externally but through his own emotional awakening. The poem teaches that self-awareness can be both enlightenment and suffering. Regret does not heal the loss; it clarifies the moral truth behind it. Henryson’s moral art lies in this transformation—he converts emotional pain into spiritual recognition. By understanding the weight of his mistake, Robene achieves moral growth, though too late for reconciliation. The poem thus offers moral education through inner realization rather than external retribution.

Human Desire and Moral Balance

Henryson’s moral insight extends beyond individual error. He examines the nature of desire itself. Love, in his view, becomes moral when guided by humility, patience, and awareness. When driven by pride or blindness, it turns destructive. The poem illustrates the moral necessity of balance—between feeling and reason, pursuit and restraint. Makyne’s early openness contrasts Robene’s coldness; her later rejection contrasts his sudden passion. Neither extreme achieves harmony. True virtue lies in measured affection, free from vanity or haste. The poet’s balanced view reflects medieval Christian morality, where moderation sustains virtue and excess leads to error.

Makyne’s Moral Strength

Makyne’s transformation embodies moral constancy and self-respect. At first, she appears vulnerable and pleading. Yet her later composure reveals inner strength and wisdom. By refusing Robene after his change of heart, she asserts moral agency. Her firmness demonstrates that love without sincerity or timing loses worth. She becomes the moral victor not through revenge but through dignity. Henryson presents her as a figure of self-knowledge, uniting emotional truth with moral firmness. Her character thus conveys a lesson about integrity—one must value oneself even when love fails. Makyne’s calm decision restores the poem’s moral and emotional order.

Robene’s Repentance as Moral Enlightenment

Robene’s belated love transforms him from a carefree shepherd into a reflective soul. His regret represents spiritual awakening. The pain he feels is both punishment and purification. Henryson does not mock his sorrow; he elevates it into understanding. Robene’s recognition that opportunity cannot be reclaimed reflects moral awareness. He learns that neglect has lasting consequences, both emotional and ethical. Through this transformation, the poet demonstrates that repentance holds value even when it cannot reverse fate. The lesson is deeply moral—wisdom often arrives through suffering. Robene’s enlightenment thus becomes the poem’s quiet redemption.

Irony and Moral Reflection

Irony serves as the poem’s chief instrument of moral instruction. Henryson’s irony is gentle, never cruel. It reflects the balance between justice and compassion. The reversal of roles provides humor, yet that humor conceals a serious moral truth. The irony of timing and reversal encourages reflection rather than ridicule. Readers see themselves in both Robene and Makyne—too slow to feel, too quick to dismiss, and too proud to forgive. Through irony, Henryson reveals moral reality without preaching. His wisdom emerges naturally from human behavior, showing that life itself enforces moral balance through its own patterns.

Universal Moral Relevance

Although rooted in medieval Scotland, the poem’s moral truths remain universal. Its message about timing, pride, and regret transcends its pastoral setting. Every age understands the pain of missed chances and the wisdom gained through loss. Henryson’s moral vision rests on enduring principles—truth, awareness, and humility. He teaches that love without discernment becomes folly, and regret without change becomes despair. The moral insight of the poem thus belongs not only to its characters but to humanity as a whole. Its enduring power lies in the recognition that emotional choices carry moral weight.

Conclusion: Moral Harmony through Human Experience

Ultimately, Henryson’s moral vision unites emotion, wisdom, and justice. Through simple dialogue, he expresses profound ethical thought. The poem shows that moral truth arises not from authority but from experience. Love, regret, and reflection become tools of moral understanding. The pastoral simplicity conceals complex ethical harmony, where every act and emotion finds moral consequence. Henryson’s genius lies in transforming rustic affection into spiritual allegory. The moral interpretation of this work continues to inspire because it portrays truth with humanity and grace. Through compassion and irony, Henryson proves that moral art endures by reflecting life’s deepest rhythms of choice, error, and redemption.

Historical and Literary Importance of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction: Contextual Value of Henryson’s Work

Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson occupies a central position within late medieval Scottish literature. It represents not only a poetic gem of the fifteenth century but also a transitional work linking medieval allegory with early Renaissance sensibility. Henryson’s poetic genius emerges in his ability to merge moral reflection with vivid human feeling. His poem reflects the Scottish courtly tradition while also embracing rustic simplicity. Historically, it demonstrates how Scotland developed an independent poetic identity distinct from both English and Continental models. The poem’s significance thus extends beyond its narrative charm—it stands as a cultural bridge between medieval morality and Renaissance individualism.

Scotland’s Literary Awakening

The fifteenth century marked a flourishing period for Scottish literature. Writers such as Henryson, Dunbar, and Douglas shaped a national literary voice. Robene and Makyne fits perfectly into this awakening. It reflects Scotland’s growing self-awareness in literature, where vernacular expression carried moral authority. Henryson’s work demonstrates that serious moral reflection could coexist with rustic humor. This blending of tones reflected the broader social change in Scotland, where literature began addressing common human experience instead of only courtly ideals. Thus, the poem embodies the spirit of a nation discovering its moral and cultural language through art and poetry.

The Bannatyne Manuscript and Literary Preservation

Much of Henryson’s work survives because of The Bannatyne Manuscript, compiled in 1568. This collection preserved Scotland’s literary legacy during turbulent times. The inclusion of Robene and Makyne within it highlights the poem’s esteem among early readers. It shows that Henryson’s moral craftsmanship and pastoral realism were valued not just for their entertainment but for their cultural insight. The manuscript’s compiler, George Bannatyne, recognized Henryson’s contribution to Scottish moral and lyrical poetry. The preservation of this poem ensured that future generations could witness the depth and subtlety of Scotland’s early literary achievements.

Henryson’s Role as a Transitional Poet

Henryson stands between medieval allegorists and Renaissance humanists. Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson illustrates this transition beautifully. He maintains medieval moral order while introducing psychological realism. His characters are not mere symbols; they possess emotional complexity. This balance marks Henryson’s historical importance. He bridges two eras—retaining the didactic spirit of the Middle Ages while anticipating Renaissance attention to individuality and feeling. His poetry thus serves as a vital link in the evolution of European thought. Historically, his pastoral dialogue becomes a turning point in Scottish moral poetry, transforming allegory into living emotion.

Influence of Chaucer and Divergence from English Tradition

Henryson drew inspiration from Geoffrey Chaucer, especially in rhythm and moral tone. Yet, Robene and Makyne shows how he diverged from English influence. Chaucer’s love poetry often celebrated courtly ideals, whereas Henryson turned toward rural simplicity and moral realism. He adapted English literary techniques to reflect Scottish social life and thought. This adaptation established Scotland’s independent moral voice. Henryson’s innovation lies in replacing aristocratic romance with common humanity. His version of love and regret feels intimate and moral rather than ornamental. Through this divergence, he helped define a unique Scottish poetic identity distinct from its southern counterpart.

Pastoral Tradition and Its Evolution

The pastoral mode in Robene and Makyne holds historical importance because it redefines the genre. Earlier European pastorals often idealized rural life as peaceful and harmonious. Henryson’s approach is more realistic and morally grounded. His shepherds are not perfect figures of innocence but flawed human beings learning through experience. This shift transformed the pastoral form from idyllic fantasy into moral commentary. His treatment of the countryside as both beautiful and instructive became an influential model for later poets. Therefore, the poem not only belongs to Scottish history but also contributes to the evolution of the European pastoral tradition.

Language, Dialect, and Cultural Identity

One of the most significant historical features of the poem lies in its language. Henryson’s use of Middle Scots marks an important phase in linguistic development. His diction blends courtly refinement with vernacular authenticity. Through this fusion, he affirms the dignity of the Scots tongue as a medium for literature. The poem’s rhythmic vitality and expressive clarity show that moral wisdom could thrive outside Latin or English dominance. This linguistic confidence contributed to Scotland’s emerging national identity. The use of Middle Scots also preserved the unique sound and rhythm of Scottish rural speech, giving the poem both historical and cultural texture.

Moral Literature and Civic Humanism

Henryson’s poem reflects the moral consciousness of late medieval society. It promotes reflection on personal responsibility and moral timing. Historically, this emphasis aligns with the development of civic humanism—an intellectual movement that valued moral conduct within social life. The poem’s moral vision connects individual emotion to communal ethics. It implies that moral harmony sustains not only love but also society. In this sense, Robene and Makyne belongs to a broader European current that sought to unite moral education with human experience. Its historical significance lies in showing how Scottish poetry contributed to Europe’s moral and intellectual development.

Reception and Enduring Legacy

Henryson’s poetry, though rooted in its age, maintained influence long after his death. Renaissance poets admired his moral clarity and balanced tone. Later critics recognized his realism as a precursor to psychological literature. Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson continues to be studied for its moral precision and historical richness. Its themes of timing, regret, and human frailty resonate beyond the medieval context. Scholars view it as one of the earliest psychological pastorals in European literature. Its simplicity conceals intellectual sophistication, and its humor disguises profound ethical insight. Therefore, its endurance in literary history attests to its timeless moral and artistic value.

Influence on Later Scottish Writers

Henryson’s influence can be traced through later Scottish poets such as William Dunbar and Gavin Douglas. They expanded upon his moral tone and linguistic style. His blending of moral allegory with realistic emotion became a foundation for the Scottish Renaissance tradition. The poem’s clarity, rhythm, and dialect inspired future writers to see moral poetry as both national and universal. Through his example, the Scottish poetic voice achieved confidence in expressing moral truths through local imagery and natural dialogue. His influence extended even into modern literary criticism, where Henryson’s pastoral insight continues to inform discussions of moral realism.

Historical Reflection: From Medieval Faith to Human Experience

Henryson’s work marks the transition from collective medieval faith to personal moral consciousness. His poetry demonstrates that moral truth can exist within human experience rather than solely within divine command. This shift carries historical importance because it reflects the changing worldview of late medieval Europe. The moral lessons in Robene and Makyne stem from human action and choice, not supernatural intervention. This human-centered morality foreshadows Renaissance ethics and early modern psychology. Thus, the poem becomes a historical mirror, capturing Europe’s intellectual movement from external authority to internal awareness.

Conclusion: A Timeless Moral Artifact

In sum, the historical and literary importance of Henryson’s poem rests in its dual achievement—its preservation of medieval moral tradition and its anticipation of modern psychological realism. Through a pastoral dialogue, Henryson bridges history, culture, and philosophy. His artistry ensures that moral truth survives through poetic beauty. The poem’s endurance across centuries reflects not only its aesthetic charm but also its universal moral insight. Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson remains a cornerstone of Scottish literature, embodying the union of art, morality, and national identity. It continues to represent how timeless wisdom can arise from simple hearts, rustic voices, and enduring moral faith.

Critical Interpretation of Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson

Introduction: Reading Henryson through Multiple Lenses

Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson has inspired a long tradition of literary criticism for its depth beneath simplicity. Critics have often noted how the poem’s brief pastoral dialogue conceals complex psychological, moral, and social meanings. Though it appears as a light love exchange between a shepherd and a maiden, its emotional texture reveals intricate layers of human truth. Therefore, readers and scholars alike continue to interpret Henryson’s short poem as a moral study of love, time, and choice. Modern criticism emphasizes how Henryson’s craftsmanship bridges medieval allegory and psychological realism, making this poem one of the most analyzed short works in Scottish literature.

Medieval Allegory and Moral Instruction

Early critics viewed the poem primarily as an allegory of moral failure. The dialogue between Robene and Makyne reflects not just romantic hesitation but spiritual unpreparedness. Robene’s delayed affection becomes symbolic of the soul that resists divine love until the moment passes. This reading follows the medieval tradition of using love allegory to express moral truths. Under this lens, Henryson’s pastoral simplicity conceals theological commentary. The poem warns against delaying moral or emotional response. In this interpretation, Makyne represents divine wisdom or grace, while Robene symbolizes the human heart slow to act. The moral pattern reflects Henryson’s background in didactic poetry and his belief in moral timing as the foundation of virtue.

Psychological Realism and Emotional Reversal

Modern criticism has shifted attention from moral allegory to emotional realism. Many scholars highlight the poem’s psychological balance, where both characters display human vulnerability. Robene’s hesitation mirrors emotional immaturity, while Makyne’s change of heart illustrates wounded pride and self-protection. The reversal of feeling between them gives the poem its tragic tension. This dynamic reveals Henryson’s subtle understanding of human psychology long before the rise of modern introspective literature. Furthermore, the poem’s symmetrical structure reinforces emotional reversal—each half reflects the other, yet their timing never aligns. Critics describe this as “the psychology of delay,” where emotional awareness always arrives too late. Henryson transforms ordinary dialogue into a study of consciousness, making the poem resonate with timeless realism.

Moral Irony and the Logic of Timing

Henryson’s moral irony forms one of the most discussed aspects of the poem. Critics recognize that time functions as the real antagonist. The entire narrative unfolds around misaligned desire—love that appears too late to be fulfilled. This concept echoes moral lessons found throughout Henryson’s corpus, where wisdom arises from recognizing opportunity’s brevity. Scholars have compared the poem’s moral pattern to the medieval memento mori motif, where time’s passing teaches moral awareness. However, unlike direct moral preaching, Henryson achieves this effect through irony and tone. The moral truth emerges naturally from the characters’ experience, not from authorial intrusion. This restrained technique marks the poem as both moral and modern. Through gentle irony, Henryson transforms pastoral simplicity into reflective wisdom.

Gender Dynamics and Emotional Autonomy

Recent criticism explores the poem’s treatment of gender and emotional agency. Makyne’s transformation from an affectionate maiden to an independent speaker redefines traditional gender roles. Initially, she conforms to the conventional role of the pleading lover, yet by the poem’s end, she controls the dialogue. Her rejection of Robene demonstrates emotional autonomy uncommon in medieval love poetry. Scholars interpret her shift as symbolic empowerment within a patriarchal context. Henryson allows a female voice to define moral closure, an unusual feature for the period. Furthermore, Robene’s regret underscores the moral cost of ignoring emotional sincerity. The poem, therefore, presents gender not only as social identity but as moral consciousness, where each character’s response reveals ethical growth or failure.

Tone, Humor, and Controlled Emotion

Critical discussions often emphasize the poem’s tonal complexity. Henryson uses humor not to mock but to deepen emotional resonance. The light, conversational tone allows readers to engage with serious moral themes without overt preaching. Critics have admired Henryson’s control of tone—balancing irony with empathy. His humor disarms readers, leading them toward reflection rather than judgment. The controlled rhythm of dialogue, combined with emotional understatement, reveals a masterful poetic ear. Scholars have called this blend of grace and gravity the hallmark of Henryson’s style. Through tone, he achieves moral persuasion without rigidity, demonstrating that humor and seriousness can coexist within the same poetic frame.

Comparative Criticism: Chaucer and Henryson

Critics frequently compare Henryson’s pastoral poem to Chaucer’s shorter works, especially those exploring irony in love. While Chaucer’s humor often exposes social folly, Henryson’s irony directs attention toward moral timing. Scholars note that Henryson’s characters represent ordinary Scots rather than idealized lovers. This realism transforms Chaucerian influence into something distinctly national and ethical. Henryson’s focus on emotional delay, rather than moral corruption, makes his poetry more intimate. Comparative studies show how Robene and Makyne develops themes of moral reversal and repentance found in The Testament of Cresseid. Both poems portray emotional awareness as the foundation of moral insight. Thus, Henryson’s originality lies not in invention of form but in deepening moral psychology within inherited literary structures.

Symbolism and Thematic Ambiguity

Critics often debate whether the poem’s symbols carry moral or natural meaning. The countryside setting, animal references, and rhythmic refrains seem pastoral on the surface. Yet these images also carry symbolic undertones. The shift from summer to winter mirrors emotional change, suggesting nature’s moral correspondence to human experience. The hill, the glen, and the open field each mark emotional stages of desire and withdrawal. Scholars see this as Henryson’s way of fusing natural imagery with moral reflection. The ambiguity of meaning enriches the poem’s interpretive depth. It invites both moral and aesthetic readings, confirming Henryson’s sophistication as a poet of layered symbolism.

Reception and Scholarly Perspectives

From the seventeenth century onward, critics recognized Henryson as a poet of moderation and wisdom. Early commentators praised his moral elegance and linguistic grace. In the twentieth century, scholars such as C.S. Lewis and Matthew P. McDiarmid analyzed his moral balance and realism. Contemporary criticism continues exploring psychological and gender dimensions. Academic interest remains steady because the poem speaks across ages—its moral insight appears timeless. Moreover, its linguistic richness makes it a cornerstone for studies of Middle Scots literature. Through continued scholarly attention, Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson retains relevance as a moral, psychological, and linguistic artifact of rare perfection.

Modern Relevance and Interpretive Universality

Modern readers interpret Henryson’s poem not just as a medieval artifact but as a universal moral fable. Its lesson about missed timing applies to modern relationships and decisions. The dialogue format mirrors everyday emotional conversations, where opportunities vanish through hesitation. Critics find the poem’s emotional truth remarkably contemporary. It addresses the universal human dilemma—how to act before regret replaces possibility. The simplicity of diction and precision of tone ensure its continuing resonance. In modern criticism, it represents not only Scottish heritage but also the timeless human struggle between desire and delay.

Conclusion: Henryson’s Critical Legacy

In critical discourse, Henryson stands as one of the most balanced poets of the medieval world. His humor conceals wisdom, his simplicity hides structure, and his pastoral dialogue reveals philosophical reflection. Critics agree that his art lies in restraint—saying much through few lines. The moral depth of his poetry continues to invite layered interpretation. Each new generation of scholars finds fresh meanings within his pastoral exchange. Through critical appreciation, Henryson remains alive in literary consciousness. His poem embodies the essence of human truth—simple, tender, and wise. Its emotional sincerity ensures that the lessons of timing, humility, and moral awareness endure across centuries.

Conclusion of The Whole Discussion

Revisiting the Essence of Henryson’s Poem

Robene and Makyne by Robert Henryson stands as a perfect balance between simplicity and philosophical reflection. The poem captures human experience in its purest form—desire, hesitation, and regret. Its charm lies in Henryson’s ability to present a universal theme through local speech and familiar setting. Although only a brief dialogue, the poem achieves depth unmatched by many longer works. The story’s emotional structure unfolds like a moral parable. Every line carries moral and emotional consequence. Henryson’s art transforms the pastoral landscape into a stage of conscience. The poem remains small in scale but vast in wisdom.

The Poem’s Central Lesson

The poem’s enduring power comes from its central moral insight—the danger of delayed response. Robene’s indecision and Makyne’s reversal form the heart of the moral structure. Their changing emotions illustrate how hesitation often destroys opportunity. Henryson teaches that desire must meet sincerity before time alters circumstance. This moral rhythm defines much of his poetry. Moreover, the lesson goes beyond love. It touches work, faith, and ethical choice. Every reader recognizes the truth behind its simplicity—life rewards timely understanding. Through that recognition, the poem transcends its pastoral form. Its lesson becomes spiritual rather than sentimental.

From Love Dialogue to Moral Parable

Although framed as a conversation about love, the poem speaks of moral timing. The transformation from affection to withdrawal parallels the human journey from ignorance to wisdom. Makyne’s emotional strength reflects realization, while Robene’s sorrow reveals moral delay. Henryson uses dialogue to dramatize that moral awakening. The rhythm of speech carries the weight of discovery. Because of this, the poem’s apparent simplicity conceals its allegorical force. It shows how human desire mirrors the soul’s longing for grace. As one delays, the chance for union disappears. The poem therefore turns emotional failure into spiritual lesson, teaching balance between heart and reason.

Tone of Subtle Irony

Henryson’s moral instruction works through irony rather than judgment. He never condemns Robene directly. Instead, he allows the reader to feel sympathy through irony. The tone remains soft, even humorous, but the emotional consequence is serious. This restraint gives the poem lasting appeal. Irony becomes Henryson’s instrument for moral teaching without bitterness. It draws readers into reflection rather than forcing instruction. Because of this tone, the poem remains accessible to modern sensibility. Its moral message feels human, not didactic. Through irony, Henryson achieves moral clarity with artistic grace.

Language, Music, and Structure

The poem’s musical rhythm enhances its emotional resonance. The short, regular stanzas create a pattern of approach and withdrawal, mirroring the characters’ emotional movement. Repetition of phrases strengthens the poem’s musical quality while emphasizing thematic contrast. The language itself combines Scots realism with lyrical fluency. Henryson’s diction preserves the natural speech of the countryside yet achieves refinement through rhythm. Critics often note how sound and meaning blend in perfect harmony. The structure of alternating voices reinforces emotional tension. Each stanza feels like a heartbeat in dialogue. Through music, Henryson turns ordinary speech into moral poetry.

Emotional Symmetry and Human Truth

The poem achieves emotional symmetry through reversal. At the beginning, Makyne loves while Robene withdraws. By the end, Robene loves while Makyne withdraws. This symmetry forms the poem’s inner design. It demonstrates the pattern of human experience—one seeks while another refuses, then the roles change. The emotional truth feels inevitable. Henryson captures that shift with tenderness, not cruelty. Readers feel both compassion and regret. The poem thus reveals human emotion as a cycle rather than an event. Its emotional rhythm reflects life itself—ever turning, ever incomplete. Through that balance, Henryson captures universal human feeling in a few simple lines.

Moral Reflection and Human Responsibility

Beyond emotional truth lies moral responsibility. Henryson suggests that wisdom grows through recognition of missed chances. Robene’s sorrow teaches readers the value of moral alertness. Makyne’s decision illustrates dignity through self-control. Together, they embody two forms of moral choice—awareness and restraint. The poem therefore functions as a moral mirror. It invites readers to reflect on their own choices and timing. Every delay carries consequence. Every decision defines character. In this way, Henryson turns everyday emotion into ethical reflection. The poem encourages mindfulness, showing how time’s movement shapes moral awareness.

Social Commentary within the Pastoral Frame

Though pastoral in setting, the poem contains subtle social observation. The world of shepherds mirrors human society. Simplicity becomes a mask for moral universality. Henryson writes of humble figures, yet their emotions carry the weight of every class. The poem reflects an ideal where emotional honesty belongs to all people. Robene and Makyne’s exchange transcends rank or learning. In a world shaped by hierarchy, Henryson’s choice of simple lovers shows democratic moral vision. Every human soul faces the same challenge—to act before time closes the door. The pastoral frame therefore hides profound social wisdom beneath rustic charm.

Continuity within Henryson’s Moral Vision

Throughout Henryson’s works, moral understanding depends on personal realization. The same pattern appears in The Testament of Cresseid and The Morall Fabillis. In each, characters face moral awakening through experience. Robene and Makyne represents that theme in miniature. The moral truth emerges through quiet dialogue rather than grand tragedy. Henryson demonstrates that insight often comes through ordinary exchange. The poem unites ethical reflection with emotional realism, creating perfect proportion. It proves that moral art does not require elaborate structure, only truthful feeling. Through this poem, Henryson crystallizes his lifelong vision—wisdom through recognition and repentance.

Cultural Legacy and Enduring Relevance