Part 1: Background and Early Influences

1. Introduction to the Romantic Period in Literature

The Romantic Period in Literature marks a truly transformative era in English writing. It emphasizes deep emotion, wild imagination, and the purity of nature.1 Furthermore, writers rebel against the cold rationalism of the previous age. Indeed, they seek a more authentic and personal way to view the world. Consequently, transition words connect intellectual, social, and literary shifts effectively for every reader. Readers observe growing individualism and the celebration of raw creativity in every poem.2 Moreover, poetry, prose, and novels all reflect this dynamic change quite clearly. The era values personal expression, emotional depth, and a reflection on human experience.3 Thus, Romantic writers explore freedom, beauty, and the sublime consistently.4 Additionally, transition words link historical context with literary production naturally. Surely, literary innovation emerges as writers challenge the old classical rules of the past.5 Meanwhile, the period encourages experimentation while promoting national identity and cultural reflection.6 Furthermore, its influence extends far beyond literature to philosophy and society.7 Hence, understanding this era requires observation of social, political, and literary transformation simultaneously. Truly, the movement represents a rebirth of the human spirit in art. Finally, it establishes the foundation for modern creative thought.+4

2. Historical Context of Romanticism

The Romantic Period in Literature develops alongside significant and often violent historical events. Revolutions, industrialization, and rapid political change shape the perspectives of all writers.8 Furthermore, social upheaval inspires a literary exploration of freedom and human rights. Indeed, the fall of old kings and the rise of factories changed life. Consequently, transition words connect societal events with literary output coherently and logically. Readers see how literature responds to shifting values and new cultural expectations.9 Moreover, Romantic writers emphasize emotion, imagination, and reflection in response to these events.10 Thus, literary works critique industrialization and social inequality very actively.11 Observation highlights the vital connection between context, thought, and creative expression. Additionally, literary production demonstrates personal, political, and cultural engagement simultaneously. Transition words maintain a smooth flow between historical events and the literary response. Surely, Romanticism embraces revolutionary ideals alongside a bold imaginative exploration.12 Its literature celebrates individual perception, ethical concern, and emotional depth consistently.13 Furthermore, writers sought to find beauty in a world becoming darker with smoke. Hence, history and art became inseparable during this unique time.+5

3. Key Philosophical Influences

Philosophy significantly shapes the Romantic Period in Literature through new ways of thinking. Thinkers like Rousseau and Kant influence ideas of nature and human emotion. Furthermore, imagination and intuition gain importance over dry, cold reason.14 Indeed, the mind is seen as an active creator of the universe. Consequently, transition words connect philosophy to literary themes seamlessly and effectively. Readers observe how intellectual currents guide creativity and deep reflection. Moreover, writers incorporate moral, aesthetic, and spiritual considerations into their creative works.15 Thus, philosophy shapes narrative structure, poetic form, and thematic exploration. Observation highlights the interplay of thought and literary expression in every stanza. Additionally, transition words link philosophical influence with literary innovation coherently. Surely, Romantic literature values emotional authenticity and subjective experience very deeply.16 Its works explore freedom, individualism, and the sublime consistently.17 Furthermore, ethical and imaginative concerns intertwine naturally throughout the literature of the age. Hence, philosophical foundations provide structure, depth, and reflection in Romantic writing.18 Truly, the movement was a search for truth within the self. Finally, it proved that the heart has its own logic.+4

4. The Role of Nature

Nature emerges as a central theme in the Romantic Period in Literature.19 Writers portray landscapes, seasons, and natural phenomena quite vividly.20 Furthermore, nature symbols reflect emotion, spirituality, and a sense of freedom. Indeed, the wild woods are seen as a divine temple for man. Consequently, transition words connect imagery with thematic meaning effectively and clearly. Readers recognize nature as both a setting and a deep metaphor simultaneously.21 Moreover, poetry, essays, and novels celebrate beauty and the sublime consistently.22 Thus, reflection on nature encourages moral and philosophical contemplation for everyone. Observation demonstrates how landscapes reflect inner experience and the power of imagination. Additionally, transition words link descriptive elements to ethical and emotional lessons naturally. Surely, writers contrast industrial development with natural purity quite actively.23 Romantic literature values imagination shaped through a close engagement with the natural world.24 Furthermore, its emphasis reinforces emotion, insight, and aesthetic appreciation continuously.25 Hence, nature provides symbolic, ethical, and thematic depth across all genres consistently. Truly, the outdoors became the new church for the Romantic poet.+5

5. Emotional Expression and Individualism

Romantic literature emphasizes emotion and the unique individual experience above all else.26 Writers prioritize subjective perception over objective reason in their daily work.27 Furthermore, personal feelings guide the narrative and poetic development of every piece.28 Indeed, the “I” becomes the most important word in the language. Consequently, transition words connect emotion with imagination, reflection, and moral consideration. Readers perceive deep human insight through lyrical and narrative expression. Moreover, poetry and prose celebrate passion, melancholy, and joy consistently.29 Thus, literature portrays personal struggle, triumph, and reflection vividly for the audience. Observation highlights the celebration of the self within broader cultural contexts. Additionally, transition words maintain a flow between internal experience and literary form. Surely, writers explore identity, creativity, and imagination actively.30 Furthermore, emotional expression shapes style, theme, and narrative cohesion continuously.31 Hence, Romantic literature promotes authenticity, reflection, and imaginative freedom consistently.32 Truly, it taught the world that feelings are a valid source of truth.33 Finally, it gave a voice to the lonely and the dreaming soul.+7

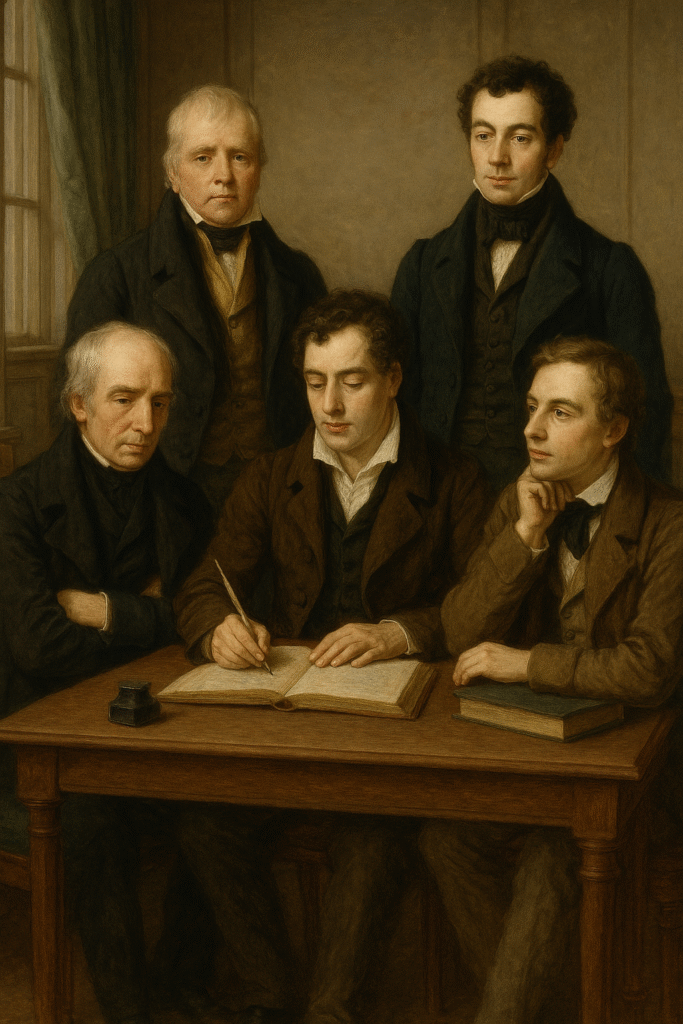

6. Early Romantic Writers

The Romantic Period in Literature begins with early writers like Blake and Wordsworth.34 They emphasize nature, imagination, and deep spiritual reflection in their verses.35 Furthermore, their works challenge traditional poetic forms and classical conventions boldly.36 Indeed, they wanted to speak the language of the common man.37 Consequently, transition words connect early influences with literary innovation naturally. Readers observe thematic development, imagery, and personal reflection across many different texts. Moreover, poetry communicates philosophical, ethical, and aesthetic concerns effectively.38 Thus, writers integrate social commentary and moral insight seamlessly into their art. Observation highlights originality, creativity, and emotional depth in these early Romantic works. Additionally, transition words link personal experience with universal themes consistently. Surely, writers balance lyricism with narrative, reflection, and imaginative experimentation continuously. Furthermore, their works shape later Romantic expression and thematic exploration comprehensively. Hence, Blake and Wordsworth remain the giants of this new artistic dawn. Truly, they lit the fire that would burn for a century.+3

7. The Influence of French Revolution

The French Revolution impacts the Romantic Period in Literature significantly and profoundly.39 Writers respond to the ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity with passion.40 Furthermore, literature reflects political, social, and emotional turbulence quite vividly.41 Indeed, the fall of the Bastille felt like a new morning for man. Consequently, transition words link historical events with thematic and narrative development. Readers perceive revolutionary energy within poetry, prose, and essays alike.42 Moreover, writers embrace freedom, human rights, and social critique consistently.43 Thus, observation highlights the connection between politics and personal expression in art. Additionally, transition words maintain clarity between historical context and literary reflection. Surely, literature explores idealism, struggle, and moral contemplation actively.44 Furthermore, Romantic writing channels the revolutionary spirit through imaginative and emotional expression. Hence, its influence shapes narrative structure, themes, and literary purpose effectively. Truly, the hope for a better world drove the pens of many poets. Finally, even when the war turned dark, the ideals of freedom remained.+5

8. Lyrical Ballads and Literary Innovation

Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads define the early Romantic literary innovation.45 The collection emphasizes everyday life, imagination, and the power of emotion. Furthermore, simple language conveys a profound meaning effectively to all readers. Indeed, they rejected the “poetic diction” of the previous elite age.46 Consequently, transition words link poetic form with thematic exploration naturally. Readers perceive the democratization of literature and aesthetic accessibility in every poem. Moreover, observation highlights moral, social, and imaginative engagement simultaneously. Thus, literary experimentation demonstrates narrative and stylistic innovation very actively. Additionally, transition words maintain cohesion between the idea, the form, and the reflection. Surely, poetry embodies personal insight, social observation, and imaginative depth consistently. Furthermore, early Romantic works establish stylistic and thematic precedents for all later writers. Hence, their innovation fosters a connection between the reader, emotion, and imagination naturally. Truly, this book changed the course of English literature forever. Finally, it proved that great art can be found in a simple field.+1

9. Gothic Elements in Romantic Literature

Gothic elements appear in the Romantic Period in Literature through mystery and fear.47 Writers explore dark landscapes, haunted settings, and psychological tension quite vividly.48 Furthermore, imagination amplifies fear, suspense, and the aesthetic effect of the text. Indeed, the dark side of the soul is just as interesting. Consequently, transition words link narrative, symbolism, and thematic development coherently. Readers observe morality, human desire, and cultural anxiety simultaneously in these stories. Moreover, Gothic motifs complement Romantic ideals of emotion and individual experience. Thus, observation highlights the contrast between light and darkness in literature effectively. Additionally, transition words connect the setting, the plot, and the reflection naturally. Surely, writers explore human vulnerability, passion, and imagination actively.49 Furthermore, Gothic elements enrich narrative, ethical, and aesthetic complexity consistently. Hence, literature integrates suspense, philosophical reflection, and imaginative freedom seamlessly. Truly, the ghost story became a way to talk about the mind. Finally, it added a thrill to the search for truth.+2

10. Imagination and Creativity

Imagination defines the Romantic Period in Literature as a guiding and sacred principle.50 Writers prioritize inventive thought and emotional insight over simple factual observation. Furthermore, creativity shapes narrative, poetic form, and thematic development in every work.51 Indeed, the imagination is the power that links man to God. Consequently, transition words connect imagination with reflection, observation, and ethical consideration effectively. Readers perceive originality, insight, and expressive power clearly in the text. Moreover, literary works emphasize personal perception and inventive exploration consistently.52 Thus, observation links inner experience with narrative and symbolic meaning naturally. Additionally, transition words maintain a flow between the idea, form, and interpretation. Surely, imagination enables writers to explore freedom and moral reflection effectively.53 Furthermore, Romantic literature values creativity as both a method and a message continuously. Hence, its emphasis fosters emotional, aesthetic, and intellectual engagement seamlessly. Truly, the mind was no longer a mirror, but a lamp.54 Finally, it allowed writers to build worlds that never existed before.+4

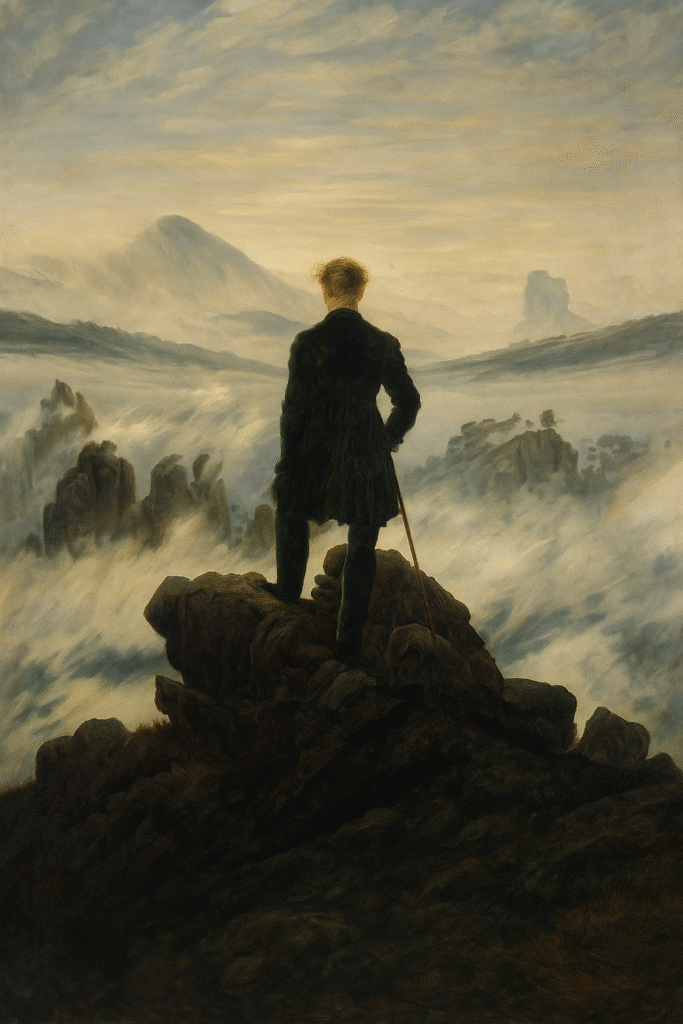

11. Romantic Hero and Subjectivity

The Romantic hero embodies individuality, emotion, and a rebellion against social convention.55 Literature emphasizes personal struggle, reflection, and difficult ethical choices.56 Furthermore, subjectivity shapes the narrative perspective and the thematic exploration consistently.57 Indeed, the hero is often a lonely figure against the world. Consequently, transition words connect character development with social, moral, and imaginative concerns. Readers observe heroes negotiating freedom, responsibility, and identity actively. Moreover, observation highlights the tension between personal desire and societal norms naturally. Thus, reflection emphasizes ethical and aesthetic engagement across many different texts. Additionally, transition words link the plot, the insight, and the meaning coherently. Surely, Romantic literature prioritizes internal perception and imaginative experience consistently.58 Furthermore, heroes embody courage, moral insight, and creativity effectively.59 Hence, their journeys illuminate emotion, ethical reflection, and narrative cohesion seamlessly. Truly, the hero showed that one man can stand for a truth. Finally, his struggle became our own.+4

12. Poetry as Primary Expression

Poetry dominates the Romantic Period in Literature as the chief expressive form. Writers convey emotion, imagination, and philosophical reflection through beautiful verse.60 Furthermore, lyrical, narrative, and meditative poetry convey thematic and moral insight effectively. Indeed, the poet was seen as the “unacknowledged legislator” of the world.61 Consequently, transition words connect style, imagery, and reflection naturally. Readers observe rhythm, diction, and metaphor enhancing the meaning consistently.62 Moreover, poetry emphasizes personal perception, social observation, and aesthetic exploration.63 Thus, observation highlights the interplay between content and form actively. Additionally, transition words maintain cohesion between the idea, the structure, and the interpretation. Surely, Romantic verse fosters ethical reflection, imaginative insight, and emotional engagement. Furthermore, writers achieve narrative and thematic depth through poetic innovation continuously. Hence, poetry remains central to Romantic expression and literary influence seamlessly. Truly, it was the perfect language for the human heart. Finally, it remains the most famous part of this age.+3

13. Role of Ballads and Folk Influence

Ballads and folk tradition inspire the Romantic Period in Literature significantly.64 Writers draw on oral narrative, ancient legend, and popular culture naturally.65 Furthermore, literature integrates simple diction, emotion, and moral reflection with ease. Indeed, they wanted to capture the “soul” of the people. Consequently, transition words connect tradition, innovation, and imaginative exploration effectively. Readers observe how folklore informs narrative structure and thematic depth consistently.66 Moreover, observation highlights the connection between social memory and personal expression actively. Thus, reflection emphasizes accessibility, ethical insight, and aesthetic engagement for all. Additionally, transition words maintain a flow between folk content and literary adaptation. Surely, Romantic literature celebrates cultural heritage, creativity, and personal insight continuously.67 Furthermore, folk elements enhance narrative, symbolic, and ethical richness effectively. Hence, literature demonstrates how tradition and imagination converge seamlessly. Truly, the old songs found a new life in high art. Finally, it helped countries find their own unique voices.+3

14. Early Novelists in Romantic Era

The Romantic Period in Literature includes influential novelists like Mary Shelley and Austen.68 Their works explore human emotion, society, and imagination quite vividly.69 Furthermore, novels integrate ethical reflection, narrative structure, and character development naturally. Indeed, they brought the Romantic spirit into the world of prose. Consequently, transition words link the plot and theme to reader engagement effectively. Readers observe social commentary, personal conflict, and imaginative creativity simultaneously. Moreover, observation highlights the integration of narrative, ethical, and aesthetic concerns consistently. Thus, reflection demonstrates the interaction between historical context and literary purpose. Additionally, transition words maintain cohesion between events, moral insight, and thematic depth. Surely, novels embody Romantic ideals through reflection, imagination, and social commentary actively. Furthermore, writers balance narrative, ethical, and aesthetic elements continuously. Hence, literature reveals innovation, insight, and cultural awareness seamlessly. Truly, the novel became a powerful tool for social change. Finally, it showed that everyday life is full of drama.+1

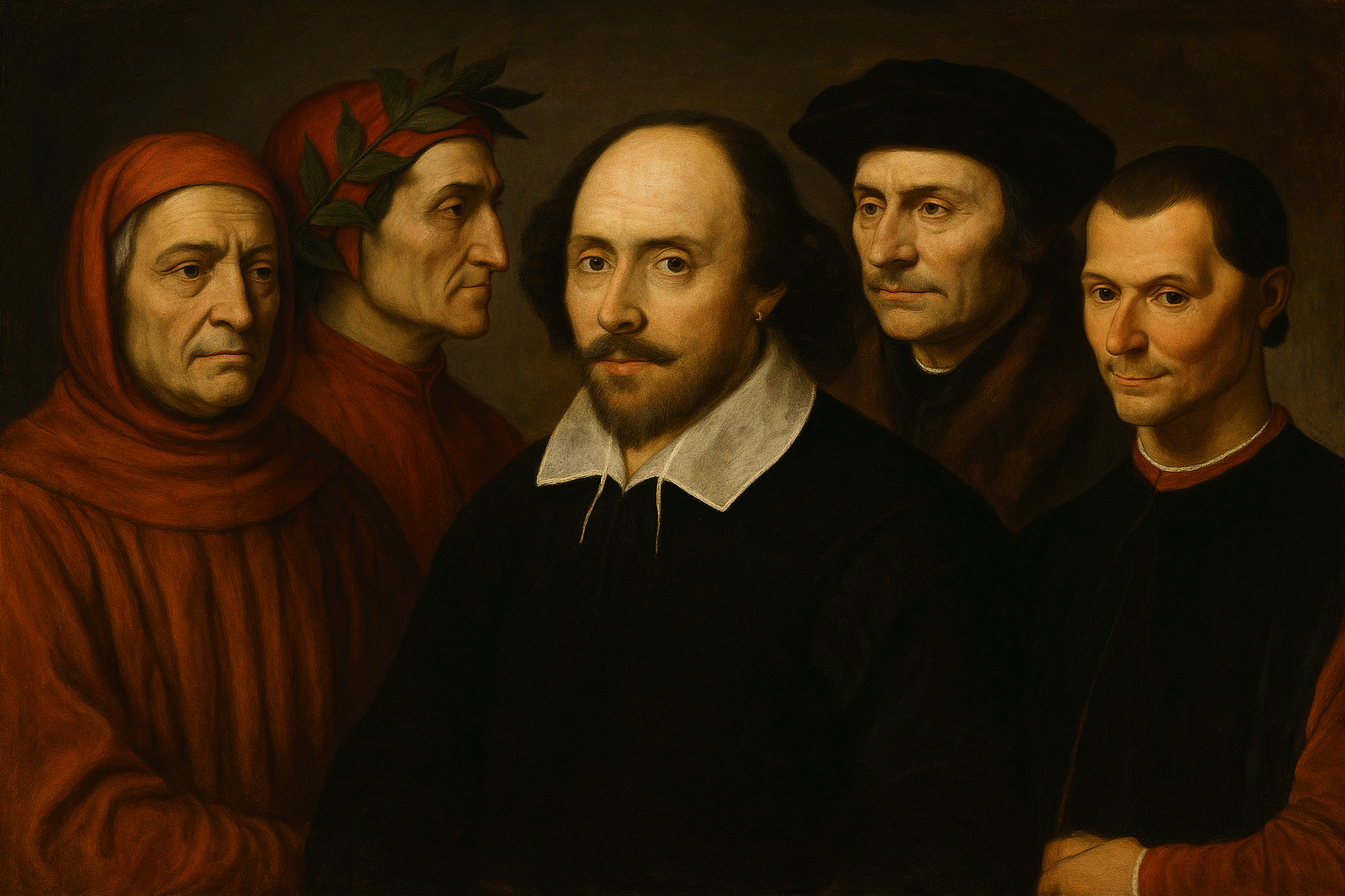

15. Influence of Milton and Shakespeare

Milton and Shakespeare shape Romantic literary style and themes significantly and deeply. Writers admire their moral complexity, imagination, and expressive power. Furthermore, narrative and poetic techniques reflect this earlier influence quite naturally. Indeed, they were seen as the great “fathers” of English genius. Consequently, transition words connect stylistic inheritance with innovation coherently and clearly. Readers observe thematic continuity, reflection, and literary experimentation actively. Moreover, observation highlights the adaptation of classical, ethical, and imaginative methods consistently. Thus, reflection demonstrates continuity between tradition and Romantic creativity. Additionally, transition words link inspiration, practice, and interpretation seamlessly. Surely, literature integrates earlier mastery with innovation, depth, and imagination continuously. Furthermore, writers balance ethical, thematic, and aesthetic considerations actively. Hence, influence shapes narrative, poetic, and philosophical sophistication effectively.70 Truly, the Romantics stood on the shoulders of giants. Finally, they proved that old spirits can inspire new songs.

16. Romanticism and Medieval Revival

Romantic writers revive medieval themes, culture, and imagination quite deliberately.71 Literature embraces chivalry, legend, and folklore consistently throughout the period.72 Furthermore, historical reflection informs the narrative, poetry, and aesthetic choices naturally. Indeed, the “Middle Ages” represented a world of magic and faith.73 Consequently, transition words connect past influences with Romantic innovation coherently. Readers observe thematic depth, imaginative engagement, and ethical reflection simultaneously.74 Moreover, observation highlights continuity, adaptation, and creative exploration actively. Thus, reflection demonstrates moral and symbolic significance consistently. Additionally, transition words maintain a flow between historical inspiration and literary form. Surely, Romantic literature integrates medieval revival with personal and imaginative expression effectively.75 Furthermore, writers explore emotion, ethical reflection, and narrative richness continuously.76 Hence, medieval influence strengthens thematic, symbolic, and aesthetic depth seamlessly.77 Truly, the knight and the castle returned to the English imagination. Finally, it added a sense of history to the dream.+6

17. Cultural Impact of Early Romanticism

The Romantic Period in Literature influences culture, thought, and social reflection profoundly.78 Poetry, novels, and essays affect artistic, intellectual, and philosophical discourse.79 Furthermore, literature shapes public taste, education, and aesthetic ideals consistently. Indeed, it changed how people viewed the world and themselves. Consequently, transition words link literary production with social, moral, and cultural effect. Readers observe an interplay between imagination, ethics, and societal transformation actively. Moreover, observation highlights the influence on painting, music, and philosophy continuously.80 Thus, reflection demonstrates the integration of literature with social consciousness effectively. Additionally, transition words maintain cohesion between literary, cultural, and historical elements naturally. Surely, Romantic works shape moral, aesthetic, and imaginative values actively.81 Furthermore, literature inspires ethical reflection, personal insight, and cultural awareness consistently. Hence, its impact extends beyond literature, guiding society, thought, and creativity naturally.82 Truly, we still live in a world shaped by Romantic dreams. Finally, it remains a model for all human expression.+2

Part 2: Themes, Poetry, and Major Works

18. Central Themes in Romantic Literature

Romantic literature explores themes of nature, imagination, and emotion. Writers reflect on human experience, freedom, and creativity. Furthermore, ethical reflection accompanies artistic exploration consistently. Transition words link personal insight with societal, moral, and aesthetic concerns naturally. Readers observe how narrative and poetry emphasize individuality and perception. Imagination drives exploration of beauty, the sublime, and human passion. Furthermore, reflection demonstrates interconnection between morality, thought, and literary innovation. Transition words maintain cohesion between theme, emotion, and narrative development. Romantic works examine heroism, human struggle, and ethical choices actively. Literature fosters introspection, imaginative engagement, and cultural reflection simultaneously. Themes shape narrative, poetic form, and reader interpretation continuously. Observation highlights interplay of personal insight, societal values, and imagination effectively.

19. Poetry as Emotional Expression

Poetry dominates Romantic Period in Literature as a medium for emotion. Writers convey feeling, imagination, and reflection vividly. Furthermore, lyricism allows intimate exploration of personal and universal experience. Transition words connect imagery, theme, and reflection coherently. Readers observe how nature, love, and melancholy inspire creativity consistently. Poetic form enhances expression of ethical, aesthetic, and philosophical ideas effectively. Furthermore, observation highlights the connection between verse, moral insight, and imagination. Transition words maintain clarity between emotion, reflection, and artistic expression naturally. Romantic poetry explores passion, freedom, and the human spirit actively. Literature integrates personal perception with cultural and ethical reflection seamlessly. Poetry remains central to narrative, ethical, and imaginative depth continuously.

20. Major Poets and Their Contributions

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Shelley, and Keats define the Romantic Period in Literature. Their poetry emphasizes nature, emotion, and imagination vividly. Furthermore, each poet shapes thematic, ethical, and aesthetic innovation uniquely. Transition words link ideas, imagery, and reflection effectively. Readers observe creativity, moral insight, and stylistic experimentation consistently. Observation highlights interplay between personal perception, social context, and literary craft naturally. Furthermore, reflection demonstrates narrative, symbolic, and thematic depth actively. Transition words maintain cohesion between literary form, content, and interpretation. Romantic poets inspire imagination, ethical reflection, and aesthetic appreciation continuously. Their works establish precedent for narrative and poetic innovation seamlessly. Literature thrives through individual contribution, reflection, and artistic engagement effectively.

21. Romantic Prose and Novels

The Romantic Period in Literature extends to prose and novels with a very significant impact. These works place a heavy and constant emphasis on raw emotion and wild imagination. Writers explore morality, identity, and social reflection vividly for their many readers. Furthermore, narrative structure highlights character development and difficult ethical dilemmas in every plot. Indeed, personal insight remains a core and vital goal of the novelist. Consequently, transition words connect plot, theme, and reflection quite effectively for clarity. Readers observe the interplay of society, nature, and individual perception in prose. Moreover, novels and essays balance story and imaginative depth naturally and smoothly. Thus, observation demonstrates the integration of personal and social concerns quite actively. Additionally, transition words maintain coherence between narrative and aesthetic exploration for everyone. Surely, literature values introspection, human experience, and imaginative freedom continuously throughout life. Romantic prose also complements poetry in shaping a wider cultural understanding today. Meanwhile, writers use the novel to challenge old and rigid social rules. Furthermore, the prose of this era remains essential and powerful for scholars. Hence, it offers a deep look at the human soul and heart. Truly, these books changed the way people read and think forever. Finally, the Romantic novel remains a peak of English art and culture.

22. Gothic Influence in Romantic Writing

Gothic literature shapes the Romantic Period in Literature very deeply and permanently. It achieves this by exploring mystery, suspense, and the strange supernatural world. Writers examine fear, desire, and human vulnerability vividly in their dark prose. Furthermore, imaginative and emotional intensity enhances the narrative and reflection for readers. Indeed, the dark side of the human mind becomes a central focus. Consequently, transition words link setting, character, and thematic depth quite naturally. Readers observe the interplay of darkness, morality, and imagination consistently in stories. Moreover, Gothic motifs enrich narrative tension and the aesthetic experience for all. Thus, reflection highlights psychological, ethical, and social concerns quite actively and boldly. Additionally, transition words maintain cohesion between suspense, symbolism, and narrative progression daily. Surely, Romantic Gothic literature emphasizes imagination, emotion, and moral insight very clearly. Meanwhile, observation demonstrates the integration of narrative and creative exploration quite seamlessly. Furthermore, the ghost story serves as a tool for reaching the truth. Hence, writers use terror to reveal the hidden human heart and soul. Truly, the Gothic spirit adds a vital thrill to all literature. Finally, it remains a favorite genre for many modern readers and fans.

23. Nature and the Sublime

Nature and the sublime dominate Romantic literature in a bold and powerful way. They emphasize beauty, awe, and spiritual reflection for the weary human soul. Writers connect landscapes with emotion, imagination, and ethical insight consistently and deeply. Furthermore, poetic depiction communicates universal and personal experience quite vividly for the public. Indeed, the vast mountains inspire a sense of divine and holy wonder. Consequently, transition words link imagery, moral lessons, and philosophical reflection quite naturally. Readers observe the interaction between natural setting and inner perception very clearly. Moreover, observation highlights symbolic and thematic richness in every single poetic stanza. Thus, reflection demonstrates ethical, aesthetic, and imaginative exploration very effectively and purely. Additionally, transition words maintain clarity between narrative, reflection, and deep artistic insight. Surely, Romantic literature celebrates the sublime as a conduit for human emotion. Meanwhile, its depiction inspires aesthetic appreciation and a deep narrative depth today. Furthermore, the wild world acts as a mirror for the modern man. Hence, nature provides a path to a higher and spiritual truth. Truly, the sublime remains the most powerful Romantic concept in art. Finally, it teaches us to respect the earth’s great power and glory.

24. Romantic Imagination and Creativity

The Romantic Period in Literature prioritizes imagination as central to all creative writing. Writers explore freedom, originality, and emotional depth vividly in every single verse. Furthermore, creativity shapes narrative, poetry, and thematic construction very effectively and boldly. Indeed, the mind is seen as a holy and creative lamp. Consequently, transition words connect perception, insight, and moral reflection quite naturally. Readers observe innovation in form, style, and expression consistently and clearly. Moreover, observation highlights the ethical, aesthetic, and imaginative interplay actively in works. Thus, reflection demonstrates originality, emotional insight, and narrative cohesion for the student. Additionally, transition words maintain flow between creative expression and deep literary interpretation. Surely, Romantic literature values imagination as a method and a moral guide. Meanwhile, literature integrates innovation, reflection, and aesthetic richness quite seamlessly and perfectly. Furthermore, the act of creation is a form of political rebellion. Hence, the writer becomes a visionary leader for the common people. Truly, imagination is the heartbeat of this entire literary age today. Finally, it allows the human spirit to fly very high and free.

25. Romanticism and Industrialization

Industrialization shapes Romantic literature by inspiring a fierce critique of modern society and human experience. Writers reflect on social inequality and the cold mechanization of life quite vividly. Furthermore, they mourn the rapid environmental change caused by the new smoky factories. Indeed, the dark mills represent a threat to the human soul and nature. Consequently, literature emphasizes raw emotion and ethical reflection as a necessary defense. Moreover, poets consistently contrast the rural past with the harsh industrial present. Thus, the green fields become a symbol of lost spiritual purity. Additionally, transition words link the social context to the imaginative response very naturally. Readers observe a clear tension between industrial progress and emotional values actively. Surely, writers highlight the moral and aesthetic costs of the machine age. Furthermore, reflection demonstrates a sharp ethical critique alongside bold creative expression effectively. Transition words maintain a strong cohesion between societal observation and philosophical reflection. Romantic literature balances social commentary and emotional depth seamlessly for the reader. Its critique fosters a new awareness and literary innovation continuously throughout the era. Finally, it challenges the idea that progress only comes from machines.

26. The Byronic Hero

The Byronic hero defines Romantic narrative and poetic exploration in a truly striking way. Writers emphasize individuality and a spirit of dark rebellion very vividly. Furthermore, an intense emotional struggle shapes the thematic and narrative depth effectively. Indeed, this character type remains one of the most famous literary icons. Consequently, transition words connect the character and the plot to ethical reflection naturally. Readers observe a constant tension between personal desire and societal expectation actively. Moreover, the hero often carries a secret burden or a past sin. Thus, observation highlights a deep psychological and moral engagement continuously. Additionally, reflection demonstrates the integration of character and theme within the narrative effectively. Transition words maintain a tight cohesion between internal conflict and moral insight. Surely, Romantic literature celebrates heroic individuality and imaginative engagement quite seamlessly. Its characters illustrate human complexity and narrative richness consistently in every single work. Furthermore, the Byronic hero represents the peak of the solitary and moody genius. Consequently, this figure influences many later writers during the Victorian and modern ages. Truly, he stands as a symbol of the restless and searching soul.

27. Romanticism and Mythology

Myth and legend influence the Romantic Period in Literature extensively and very deeply. Writers reinterpret classical and medieval sources with a high level of creativity. Furthermore, mythology provides a rich symbolic and imaginative depth for the modern poet. Indeed, ancient stories offer a way to explore universal human truths. Consequently, transition words link the cultural heritage to the thematic exploration naturally. Readers observe an active interplay between old tradition and new innovation. Moreover, observation highlights the symbolic richness of these ancient tales continuously. Thus, mythology becomes a tool for expressing complex ethical and aesthetic significance. Additionally, transition words maintain a smooth flow between the myth and the insight. Surely, Romantic literature integrates cultural memory and moral reflection quite seamlessly. Mythology enhances the ethical and the thematic expression of the period consistently. Furthermore, writers use folklore to ground their works in the national spirit. For instance, they find magic in the local legends of the British Isles. Hence, the old gods and heroes live again in the new poetry. Truly, myth serves as the foundation for the highest flights of imagination.

28. Nationalism and Patriotism

The Romantic Period in Literature often celebrates national identity and historical heritage vividly. Writers explore patriotic sentiment and the weight of history with great passion. Furthermore, literature emphasizes a shared collective and ethical reflection consistently. Indeed, the love of the homeland becomes a central theme for many. Consequently, transition words connect national consciousness to the narrative engagement naturally. Readers observe an interplay of history and individual insight in every book. Moreover, observation highlights the social and the moral engagement of the people continuously. Thus, the land itself becomes a character in the grand national story. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a deep ethical and imaginative depth within the prose. Transition words maintain a clear cohesion between the historical narrative and symbolism. Surely, Romantic literature integrates patriotism and imaginative expression quite seamlessly. Its works inspire a new cultural awareness and narrative richness consistently. Furthermore, writers seek to preserve the songs and the stories of the past. Hence, they build a sense of belonging through the power of art. Truly, the movement helps define the modern idea of a national heart.

29. Romanticism and Religion

Religious reflection shapes the moral and the imaginative dimension of Romantic literature. Writers explore spiritual experience and the divine in nature quite vividly. Furthermore, literature integrates deep imagination and personal reflection with social concern. Indeed, many poets find God in the sunrise or the mountain peak. Consequently, transition words link the narrative to the philosophical thought naturally. Readers observe an active interplay of belief and the human imagination. Moreover, observation highlights the ethical and the spiritual integration of the soul continuously. Thus, religion moves away from the church and into the wild world. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a high level of creativity and moral contemplation effectively. Transition words maintain a steady cohesion between the spiritual and the narrative elements. Surely, Romantic literature combines religion and ethical reflection in a seamless way. Its works emphasize personal experience and a deep narrative depth consistently. Furthermore, the search for the infinite guides the poet toward a higher truth. Hence, the spiritual life becomes a journey of the individual mind. Truly, faith is reborn as a personal and a creative force.

30. Romanticism and Philosophy

Philosophy guides the Romantic Period in Literature by emphasizing perception and ethics. Writers explore the nature of knowledge and human experience very vividly. Furthermore, reflection informs the imaginative and the poetic creation of the age. Indeed, the mind is seen as an active creator of reality. Consequently, transition words connect the intellectual and the literary dimensions naturally. Readers observe an interplay of thought and creative expression in every text. Moreover, observation highlights the philosophical depth and the imaginative innovation continuously. Thus, the study of the soul becomes a central literary task. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a clear ethical and thematic integration effectively. Transition words maintain a firm cohesion between the abstract concept and the narrative. Surely, Romantic literature integrates philosophy and ethical insight quite seamlessly. Its works promote a high level of intellectual and artistic engagement consistently. Furthermore, the focus on the “sublime” provides a new philosophical category. Hence, writers grapple with the vast and the awe-inspiring mysteries of life. Truly, philosophy provides the logic behind the highest flights of poetic fancy.

31. Romantic Period and the Novel

The Romantic Period in Literature embraces the novel as a key form. Writers explore emotion and individual experience within society very vividly. Furthermore, novels emphasize character and imaginative development in a consistent way. Indeed, the prose form allows for a deep look at the heart. Consequently, transition words connect the plot to the reflection naturally. Readers observe a tension between personal desire and social expectation actively. Moreover, observation highlights the narrative complexity and the thematic richness continuously. Thus, the novel becomes the most popular way to share new ideas. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a successful imaginative and ethical integration effectively. Transition words maintain a strong cohesion between the insight and the depth. Surely, Romantic novels balance reflection and creative exploration quite seamlessly. Their works illuminate the human experience and the ethical concern consistently. Furthermore, the rise of the Gothic novel adds a new thrill. Hence, the genre expands to include terror and the strange supernatural. Truly, the novel grows into a sophisticated tool for exploring human nature.

32. Romantic Women Writers

Women writers shape the Romantic Period in Literature in a significant way. Writers like Mary Shelley explore emotion and imagination quite vividly. Furthermore, literature emphasizes personal reflection and a strong societal critique consistently. Indeed, these authors challenge the old rules of the male world. Consequently, transition words link the biography to the thematic insight naturally. Readers observe an interaction of gender and literary expression actively. Moreover, observation highlights the ethical and the imaginative engagement continuously. Thus, the female voice brings a new depth to the era’s art. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a sharp social critique alongside the narrative effectively. Transition words maintain a flow between the personal and the literary elements. Surely, Romantic literature integrates women’s voices with cultural reflection quite seamlessly. Its works enhance the emotional and the narrative richness consistently. Furthermore, women writers often focus on the domestic and the political together. Hence, they prove that the private life has a public meaning. Truly, the movement is enriched by their unique and powerful perspectives.

33. Romanticism and Childhood

Childhood appears as a theme emphasizing innocence and the power of imagination. Writers explore moral and emotional reflection through the child’s eye vividly. Furthermore, narrative and poetry celebrate personal growth and development consistently. Indeed, the child is seen as the “father of the man.” Consequently, transition words link the perception to the reflection naturally. Readers observe an interplay between memory and ethical awareness actively. Moreover, observation highlights the ethical and the imaginative engagement continuously. Thus, the state of innocence is protected from the adult world. Additionally, reflection demonstrates a deep literary and moral depth effectively. Transition words maintain a strong cohesion between the narrative and the theme. Surely, Romantic literature values childhood as a symbolic resource quite seamlessly. Its works integrate a clear insight and ethical reflection consistently. Furthermore, writers mourn the loss of the “visionary gleam” of youth. Hence, the child becomes a symbol of the pure human spirit. Truly, childhood is treated as a sacred and a magical time.

34. Legacy of Writers

Writers in this section shape the period through innovation and reflection. Their poetry and prose influence all of the subsequent literature profoundly. Furthermore, literature integrates ethical and cultural reflection in a consistent way. Indeed, the Romantics set the stage for the modern world. Consequently, transition words connect the ideas to the thematic development naturally. Readers observe an interaction of innovation and imaginative exploration actively. Moreover, observation highlights the contribution to the narrative richness continuously. Thus, the writers of this age become the masters for later poets. Additionally, reflection demonstrates an enduring literary significance effectively. Transition words maintain a clear cohesion between the influence and the impact. Surely, Romantic literature thrives through creativity and ethical engagement seamlessly. Writers establish a firm precedent for all future imaginative exploration consistently. Furthermore, their focus on the self remains the core of modern art. Hence, we still read them to understand our own human hearts. Truly, the legacy of this age is a gift to the future.

Part 3: Later Writers, Criticism, and Cultural Legacy

35. Late Romantic Poets

Late Romantic poets continue the era’s emphasis on imagination and emotion. They explore personal reflection and social commentary with a vivid style. Furthermore, writers like Keats and Shelley refine the earlier poetic forms. Indeed, they focus on the beauty of art and mortality daily. Consequently, their verses reach a high level of aesthetic perfection now. Moreover, they use ancient myths to explore modern human struggles deeply. Thus, the late poets bridge the gap between past and present. Additionally, they value the pursuit of truth through the human senses. Therefore, every poem becomes a rich journey for the curious reader. Surely, these writers master the art of the complex lyrical ode. Meanwhile, they confront the heavy weight of fame and public duty. Furthermore, their works challenge the moral standards of the ruling class. For instance, Shelley writes about the power of the free spirit. Hence, his words inspire a sense of hope in every heart. Similarly, Keats finds eternal beauty in an old Greek urn today. Consequently, his poetry remains a peak of the English literary tradition. Truly, late Romantic poetry balances emotion and moral reflection seamlessly. Its works contribute to intellectual and imaginative richness consistently for all. Finally, these poets ensure the movement ends with a brilliant light.

36. Influence of Romantic Philosophy

Philosophical thought shapes narrative and poetic depth in a profound way. Writers reflect on ethics and the sublime with a vivid passion. Furthermore, they believe that the mind creates the world we see. Indeed, the human imagination becomes the center of all true reality. Consequently, literature integrates deep reflection and moral insight into every page. Moreover, philosophers argue that nature is a source of divine wisdom. Thus, the poet becomes a priest of the natural world daily. Additionally, they explore the tension between the self and the society. Therefore, readers encounter a new way of thinking about the soul. Surely, the search for the infinite guides the hand of writers. Meanwhile, they reject the dry facts of the old mechanical world. Furthermore, reflection highlights the unity of the heart and the mind. For instance, Coleridge explores the nature of the primary imagination quite clearly. Hence, his ideas help us understand the very root of creativity. Similarly, the sublime offers a way to experience the vast unknown. Consequently, literature fosters a deep and active ethical engagement for everyone. Truly, philosophical influence enhances narrative and imaginative depth seamlessly today. Its role strengthens the connection between the person and the universe. Finally, it provides the intellectual backbone for the entire Romantic age.

37. Romanticism and Nature Writing

Nature writing celebrates landscapes and seasons with a truly vivid intensity. Writers explore emotion and spirituality through rich natural imagery consistently. Furthermore, they view the wild earth as a living, breathing soul. Indeed, mountains and forests become sacred spaces for the human heart. Consequently, the poet finds a deep moral guide in the woods. Moreover, nature acts as a mirror for every internal human feeling. Thus, the physical world and the mind become one single entity. Additionally, writers reject the cold and grey walls of the city. Therefore, they seek the healing power of the quiet green hills. Surely, every leaf and stream tells a story of divine truth. Meanwhile, the changing seasons reflect the cycle of human life itself. Furthermore, nature writing serves as a form of high prayer daily. For instance, Wordsworth discovers the sublime in the simple mountain air. Hence, his words inspire a deep respect for the natural environment. Similarly, Coleridge finds strange magic in the ice and the sea. Consequently, readers learn to cherish the beauty of the wild world. Truly, nature writing fosters appreciation and deep personal introspection seamlessly. Its contribution enriches cultural and imaginative understanding consistently through every line.

38. Romanticism and Art

Artistic creation parallels literary imagination in the vibrant Romantic culture. Writers engage with painting and music with a very active spirit. Furthermore, they believe that all arts share a single creative source. Indeed, a poem and a painting often express the same emotion. Consequently, the visual arts inspire the written word quite directly. Moreover, writers focus on the symbolic depth found in great sculptures. Thus, art and literature work together to explore the human soul. Additionally, painters use color to evoke the same passion as verse. Therefore, the canvas becomes a stage for the drama of nature. Surely, the Romantic artist values bold expression over rigid traditional rules. Meanwhile, critics find a shared language between different types of media. Furthermore, art provides a visual path to the sublime and infinite. For instance, Turner captures the wild light of a stormy morning sun. Hence, his paintings reflect the same energy found in Romantic poetry. Similarly, the study of art improves the depth of literary description. Consequently, the era achieves a high level of aesthetic and moral harmony. Truly, Romantic artistic culture fosters creativity and imaginative depth seamlessly. Its legacy enhances interdisciplinary understanding and aesthetic appreciation consistently today.

39. Romantic Criticism

Critics analyze Romantic literature by evaluating style and deep cultural significance. They consider imagination and emotion as the primary tools of art. Furthermore, they reject the strict rules of the previous age boldly. Indeed, the critic now seeks to understand the author’s unique soul. Consequently, the focus shifts from formal structure to true internal feeling. Moreover, critics highlight the importance of the individual’s creative vision. Thus, the role of the critic becomes one of deep interpretation. Additionally, they examine how poetry can improve the moral state of man. Therefore, criticism serves as a bridge between the writer and reader. Surely, a good critic values the spark of original genius daily. Meanwhile, they debate the social impact of radical and new ideas. Furthermore, critical essays define the standards of the growing literary world. For instance, Hazlitt explores the characters of Shakespeare with fresh, vivid insight. Hence, he proves that old works can live in Romantic hearts. Similarly, the review becomes a powerful tool for shaping public taste. Consequently, the era develops a strong sense of intellectual self-awareness. Truly, Romantic criticism fosters understanding and literary evaluation seamlessly. Its role strengthens analysis and appreciation continuously across the globe.

40. Romanticism and Music

Music reflects Romantic ideals of emotion and expression quite vividly. Composers parallel the literary emphasis on introspection and deep ethical reflection. Furthermore, they believe that music can reach where words often fail. Indeed, a symphony can capture the vast scale of the sublime. Consequently, music becomes the most Romantic of all the arts. Moreover, composers use melody to tell a story of human struggle. Thus, the listener experiences a journey of the mind and heart. Additionally, music and poetry often join to create a powerful song. Therefore, the rhythm of the verse matches the beat of sound. Surely, the era values the wild and the unpredictable in music. Meanwhile, the opera explores the same themes of love and death. Furthermore, music reinforces the emotional impact of the written literary word. For instance, the works of Chopin reflect a deep and lonely melancholy. Hence, his piano pieces feel like a poem without any words. Similarly, the rise of the virtuoso mirrors the cult of genius. Consequently, music enriches the cultural and the intellectual life of society. Truly, Romantic music enriches aesthetic understanding and creative engagement seamlessly. Its influence reinforces imaginative depth and ethical reflection continuously.

41. Romanticism and Politics

Political engagement informs literature by exploring freedom and revolution vividly. Writers examine social structures and individual autonomy consistently. Furthermore, they champion human rights and personal liberty boldly. Indeed, poets often support radical change in the government. Consequently, their verses breathe the fire of political rebellion. Moreover, writers reject old tyranny and unfair laws actively. Thus, literature becomes a tool for true social justice. Additionally, they believe in the power of the common man. Therefore, poems celebrate the spirit of democratic hope daily. Surely, writers link their art to the public good. Meanwhile, they critique the failures of modern kings and queens. Furthermore, political ideas shape every major narrative during this age. For instance, Shelley writes about the fall of great empires. Hence, readers find inspiration in his bold, imaginative words. Similarly, Byron fights for Greek independence with his own life. Consequently, his legacy combines poetry with real political action. Truly, Romantic political literature fosters reflection and ethical engagement. Its contribution shapes societal discourse and cultural understanding consistently. Finally, it proves that art can change the state.

42. Romanticism and Emotion

Emotion drives narrative and poetry throughout this famous period. Writers explore passion and melancholy with great intensity. Furthermore, they value the heart over the cold mind. Indeed, joy and sorrow find a home in every verse. Consequently, feeling becomes the primary source of artistic truth. Moreover, writers celebrate the sublime power of the human spirit. Thus, readers experience the world through deep sensory details. Additionally, authors believe that raw emotion reveals the divine. Therefore, poetry captures the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings. Surely, every stanza resonates with an authentic personal touch. Meanwhile, writers reject the dry logic of the previous age. Furthermore, they emphasize the beauty of a lonely, dreaming soul. For instance, Keats explores the ache of beauty and death. Hence, his words touch the very core of our being. Similarly, Wordsworth finds peace in the quiet memory of nature. Consequently, his poems offer comfort to the weary modern heart. Truly, Romantic literature celebrates emotion as a vehicle for depth. Its emphasis enriches creativity and cultural understanding consistently. Finally, it teaches us to feel the world around us.

43. Romanticism and Social Critique

Literature critiques social inequality and industrialization with great fervor. Writers integrate imaginative and ethical elements to spark change. Furthermore, they loathe the dark smoke of the new factories. Indeed, they mourn the loss of the green countryside. Consequently, novels depict the hard lives of the poor. Moreover, writers attack the greed of the wealthy class. Thus, stories become a mirror for a broken society. Additionally, authors demand better treatment for children and laborers. Therefore, literature serves as a voice for the silent masses. Surely, they highlight the moral corruption in the growing cities. Meanwhile, they praise the simple life of the rural peasant. Furthermore, social reflection guides the path of the narrative. For instance, Blake writes about the misery of young chimney sweeps. Hence, his poems cry out against institutional cruelty and neglect. Similarly, novelists expose the vanity of high-grade social circles. Consequently, readers learn to question the status quo. Truly, Romantic literature balances critique and imaginative exploration. Its works enhance ethical insight and literary richness consistently. Finally, it challenges us to build a better world.

44. Romantic Period Novels

Romantic novels explore human experience and moral dilemmas vividly. Writers examine identity and social context with great care. Furthermore, they focus on the inner life of the protagonist. Indeed, characters face difficult choices in a changing world. Consequently, the plot moves through deep psychological transitions. Moreover, writers use local settings to ground their fantastic stories. Thus, the novel becomes a space for deep introspection. Additionally, authors blend realism with a touch of the supernatural. Therefore, readers find themselves lost in rich, complex worlds. Surely, every chapter reveals a new layer of the self. Meanwhile, the narrative structure supports a journey of personal growth. Furthermore, novelists challenge the old ideas of class and status. For instance, Austen examines the nuances of love and money. Hence, her sharp wit reveals the truth of social life. Similarly, Scott revives the history of the rugged Scottish border. Consequently, his books create a sense of national pride. Truly, Romantic novels enhance understanding and creative engagement. Their contribution strengthens cultural and literary insight consistently. Finally, they define the modern form of storytelling.

45. Romanticism and Women’s Perspective

Women writers offer unique insight into the social experience. Their literature explores emotion and creativity with great depth. Furthermore, they challenge the limits placed upon their gender. Indeed, they write about the domestic and the political spheres. Consequently, their voices provide a more complete view of life. Moreover, writers like Wollstonecraft argue for the rights of women. Thus, literature becomes a platform for serious social reform. Additionally, they use poetry to express their own hidden desires. Therefore, their work resonates with a sense of quiet strength. Surely, they observe the world with a sharp, critical eye. Meanwhile, they manage to balance home life with literary fame. Furthermore, their narratives focus on the female journey toward independence. For instance, Mary Shelley creates a masterpiece of science and fear. Hence, her work explores the ethics of creation and life. Similarly, Charlotte Smith revives the sonnet with a feminine touch. Consequently, readers see the world through a new, sensitive lens. Truly, women’s contributions enrich Romantic literature and narrative depth. Their works highlight diversity and imaginative sophistication consistently. Finally, they break the glass ceiling of the arts.

46. Romanticism and the Gothic Novel

Gothic novels explore suspense and the supernatural with passion. Writers integrate fear and moral insight into every dark plot. Furthermore, they use ancient castles to create a spooky mood. Indeed, mystery lurks behind every heavy, locked wooden door. Consequently, readers feel a thrill of terror and excitement. Moreover, writers examine the darker side of the human soul. Thus, the Gothic genre reveals our deepest, hidden anxieties. Additionally, authors use weather to reflect the inner mental state. Therefore, stormy nights signal a coming crisis for the hero. Surely, the boundary between dream and reality grows very thin. Meanwhile, ghosts and monsters represent our own social failures. Furthermore, the narrative relies on tension and a fast pace. For instance, Lewis depicts the fall of a sinful monk. Hence, the story warns against the dangers of hidden vice. Similarly, Radcliffe uses the “explained supernatural” to resolve her mysteries. Consequently, the reader finds logic at the heart of fear. Truly, Gothic Romantic novels contribute to a rich narrative depth. Literature balances imagination and narrative sophistication consistently. Finally, it haunts the mind long after the end.

47. Romanticism and Legacy in Literature

The era’s legacy influences Victorian and modern literature extensively. Writers adopt the tools of imagination and reflection today. Furthermore, they look back at the Romantics for artistic guidance. Indeed, the focus on the individual remains a core value. Consequently, modern poetry still prizes the authentic personal voice. Moreover, the love of nature continues to inspire new writers. Thus, the Romantic spirit lives on in every green poem. Additionally, the rebellion against authority stays relevant in our time. Therefore, we still value the rebel and the dreamer. Surely, the movement changed the way we view the world. Meanwhile, the legacy provides a bridge between the old and new. Furthermore, literary history owes much to these bold, creative souls. For instance, the Victorian poets built upon the Romantic foundation. Hence, their work reflects a similar search for deep meaning. Similarly, modern novelists use the techniques of the early masters. Consequently, the tradition of the novel stays strong and vibrant. Truly, the Romantic legacy fosters innovation and aesthetic richness. Its impact shapes literary and cultural understanding consistently. Finally, it remains the heartbeat of Western art.

48. Criticism and Reception

Critics evaluate Romantic literature by considering style and cultural significance. Literature integrates reflection and imagination in a unique way. Furthermore, early critics were often harsh and very unforgiving. Indeed, they feared the radical ideas of the young poets. Consequently, writers had to defend their art in public. Moreover, the “Cockney School” faced attacks from the literary elite. Thus, criticism became a battlefield for the future of taste. Additionally, modern critics praise the era for its bold innovation. Therefore, we now see the Romantics as true artistic heroes. Surely, the reception of these works has changed over time. Meanwhile, the study of these texts reveals many hidden meanings. Furthermore, evaluation helps us appreciate the skill of the authors. For instance, Jeffrey famously attacked Wordsworth for being too simple. Hence, his reviews sparked a debate about the nature of art. Similarly, later scholars found deep philosophy in the simplest verses. Consequently, the reputation of the period grew into a peak. Truly, Romantic criticism fosters comprehension and literary appreciation. Its role strengthens ethical reflection and narrative insight consistently. Finally, it ensures that these works are never forgotten.

49. Cultural Influence of Romantic Literature

Romantic literature shapes art and philosophy in a vivid way. Writers inspire imagination and aesthetic engagement across many fields. Furthermore, the movement changed how people view the natural world. Indeed, mountains and forests became places of holy worship. Consequently, tourism to wild places grew into a major trend. Moreover, composers like Beethoven captured the Romantic spirit in music. Thus, the era transformed the entire cultural landscape of Europe. Additionally, philosophers began to value the subjective over the objective. Therefore, the individual became the center of the modern universe. Surely, the impact of these ideas reached every social class. Meanwhile, painters captured the sublime beauty of the stormy sea. Furthermore, the influence of the period can be seen today. For instance, modern environmentalism has its roots in Romantic thought. Hence, we protect nature because we learned to love it. Similarly, our focus on self-expression comes from this great era. Consequently, our culture is a product of Romantic dreams. Truly, literature contributes to creativity and intellectual growth. Its impact persists across artistic and cultural domains consistently. Finally, it defines the modern human experience.

50. Conclusion: Enduring Significance

Romantic literature remains influential due to its focus on imagination. Writers shape thought and culture with their vivid, bold ideas. Furthermore, they remind us of the value of the heart. Indeed, the period stands as a peak of human achievement. Consequently, students around the world still study these great works. Moreover, the themes of freedom and love are truly timeless. Thus, the Romantic voice speaks to every new generation. Additionally, the movement proves that the mind is a kingdom. Therefore, we find hope in the words of the past. Surely, the significance of the era will never truly fade. Meanwhile, we continue to learn from their ethical reflections. Furthermore, the beauty of their language stays fresh and alive. For instance, the works of Byron and Keats still sell. Hence, their names are famous in every corner of earth. Similarly, the lessons of the period guide our own creativity. Consequently, we build our future on their imaginative foundation. Truly, Romantic writing endures as a model for literary excellence. Its significance continues to inspire reflection and imagination consistently. Finally, it is the soul of our literary history.

Comparative Study Between The Neo-Classical Age and Romantic Period in Literature

1. Historical Foundations of Art

The Neo-Classical Age relied on order and strict logic daily. Writers looked to ancient Rome for their primary artistic rules. Consequently, they valued social hierarchy and the power of reason. In contrast, the Romantic Period in Literature favored the individual spirit. This movement emerged as a bold response to rapid industrialization. Therefore, poets sought a return to the pure natural world. Moreover, they rejected the cold facts of the modern machine. Thus, the creative heart replaced the mechanical mind quite rapidly. Transition words help us see these deep historical shifts clearly. Similarly, the French Revolution inspired a desire for true liberty. Readers observe a move away from the elite ruling class. Furthermore, the new literature celebrated the voice of the common man. Hence, the focus shifted from the city to the wild. Meanwhile, the previous age emphasized the stability of the state. Indeed, this contrast defines the birth of modern artistic thought. Truly, the transition reflects a total change in human values. Finally, the shift allowed for more personal and honest expression.

2. The Power of Human Reason

The Neo-Classical Age treated reason as the highest human faculty. Writers believed that logic could solve every major social problem. Furthermore, they used clear and precise language to convey truth. Consequently, literature served as a tool for public moral instruction. Moreover, poets followed fixed structures like the famous heroic couplet. Thus, they achieved a sense of balance and perfect symmetry. In addition, the era prized objective observation over personal feeling. Therefore, the writer acted as a rational judge of society. Transition words link these intellectual ideals to the actual text. Similarly, the age avoided the messy and the unpredictable soul. Readers perceive a world governed by steady and universal laws. Indeed, clarity was the primary goal of every major author. Furthermore, they modeled their work after the great classical masters. Hence, the literature reflected a stable and very orderly universe. Clearly, this rational focus defined the spirit of the century. Truly, reason provided a solid foundation for all early art.

3. Imagination and the Creative Mind

The Romantic Period in Literature prioritized the power of the imagination. Writers viewed the mind as a holy and active lamp. Furthermore, they believed that creativity could reveal deep hidden truths. Consequently, the internal world became the center of the narrative. Moreover, poets rejected the rigid rules of the previous age. Thus, they sought a more spontaneous and organic artistic form. In addition, the movement valued the unique vision of the genius. Therefore, every poem acted as a window into the soul. Transition words show how this shift changed the creative process. Similarly, writers embraced the wild and the strange supernatural world. Readers observe a celebration of dreams and deep spiritual visions. Indeed, the imagination served as a guide toward the infinite. Furthermore, it allowed the author to transcend the physical realm. Hence, art became a journey of the restless human spirit. Clearly, this focus on creativity sparked a total literary rebirth. Truly, the heart replaced the head as the primary leader.

4. Nature as a Living Teacher

Neo-Classical writers viewed nature as a wild force for control. They preferred manicured gardens and very orderly landscape designs. Furthermore, they saw the natural world through a scientific lens. Consequently, literature focused on the laws that govern the universe. In contrast, the Romantic Period in Literature treated nature as divine. Poets saw the woods and mountains as a holy church. Therefore, they sought a deep spiritual connection with the earth. Moreover, nature acted as a mirror for every human emotion. Thus, the landscape became a living and very vocal teacher. Transition words connect the physical setting to the internal state. Similarly, writers explored the concept of the awe-inspiring sublime. Readers perceive the power of the storm and the peak. Indeed, nature provided a path to a higher moral truth. Furthermore, it offered a refuge from the dark industrial city. Hence, the wild world became the primary source of inspiration. Truly, this bond with nature defined the entire movement.

5. The Role of the Individual

Social status defined the individual during the Neo-Classical Age. Writers focused on how people behaved within a complex society. Furthermore, they valued the public man over the private soul. Consequently, literature examined manners, politics, and the social contract. Moreover, the individual was a small part of a larger machine. Thus, personal desires often took a back seat to duty. In contrast, the Romantic Period in Literature celebrated the solitary ego. Writers believed that every single person contained a vast world. Therefore, they explored the depths of the lonely and dreaming mind. Transition words link these social changes to the literary character. Similarly, the “Byronic Hero” emerged as a symbol of rebellion. Readers observe a move toward radical and deep self-expression. Indeed, the internal journey became the main focus of storytelling. Furthermore, the era championed the rights of the common individual. Hence, the private heart became the most important artistic subject. Truly, this shift created the modern concept of the self.

6. Language and Poetic Diction

Neo-Classical poets used a very formal and elevated poetic diction. They believed that art required a special and elite language. Furthermore, they used complex metaphors and many classical allusions daily. Consequently, poetry remained a luxury for the highly educated class. Moreover, the writers followed strict and very demanding metrical rules. Thus, the verse sounded polished, refined, and very professional. In addition, they avoided the common speech of the local people. Therefore, the language reflected the high standards of the court. Transition words clarify the differences between these two linguistic styles. Similarly, the Romantic Period in Literature introduced a simpler way of speaking. Wordsworth argued for the use of “real language” of men. Readers perceive a move toward clarity, honesty, and raw emotion. Indeed, the poets wanted to reach every single human heart. Furthermore, they found beauty in the simple words of peasants. Hence, the language of poetry became more accessible and democratic. Truly, this linguistic revolution changed the sound of English verse.

7. Satire and Social Critique

Satire served as the primary tool of the Neo-Classical writer. Authors used wit and irony to attack human vice boldly. Furthermore, they aimed to correct the many flaws of society. Consequently, literature functioned as a sharp and very public mirror. Moreover, poets like Pope used humor to promote rational conduct. Thus, the age valued the sharp mind of the critic. In addition, the satire was often biting, clever, and very precise. Therefore, readers learned to laugh at their own social follies. Transition words show how this tone differs from the Romantics. Similarly, the Romantic poets used a more sincere and serious tone. They critiqued society through the lens of deep human suffering. Readers perceive a move from cynical wit to heartfelt empathy. Indeed, the goal was to inspire a total social change. Furthermore, they attacked the cruelty of the new industrial system. Hence, the critique became a cry for true human justice. Truly, the method of social analysis shifted from logic to feeling.

8. The Presence of the Past

The Neo-Classical Age looked back to the Golden Age of Rome. Writers modeled their works after the epic and the eclogue. Furthermore, they sought to revive the values of ancient civilization. Consequently, the past provided a steady and very reliable guide. Moreover, they valued the wisdom of the long-dead classical masters. Thus, tradition acted as a limit on the creative mind. In addition, the era emphasized the continuity of the human experience. Therefore, writers avoided radical change in their artistic and public works. Transition words link the historical influence to the modern text. Similarly, the Romantics looked back to the dark Medieval Period. They found magic in ancient ruins and old folk legends. Readers observe a fascination with the strange and the supernatural. Indeed, the past was a place of mystery and wonder. Furthermore, they revived the ballad and the old sonnet forms. Hence, the history served as a source of wild imagination. Truly, both ages used the past to define the present.

9. Emotion and Artistic Truth

The Neo-Classical Age viewed raw emotion as a dangerous force. Writers believed that feelings should stay under the control of reason. Furthermore, they valued the steady and the predictable human mind. Consequently, art expressed the universal truths of the human condition. Moreover, personal outbursts were seen as weak and very unprofessional. Thus, the poet remained a cool and very detached observer. In addition, the era sought a balanced and a calm expression. Therefore, the work reflected the order of the rational universe. Transition words help us compare this to the Romantic view. Similarly, the Romantics believed that emotion was the root of truth. They saw the “spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” as art. Readers perceive an intense and a very raw emotional energy. Indeed, the heart provided the only true path to wisdom. Furthermore, they celebrated the extremes of both joy and despair. Hence, the poem became a record of an emotional journey. Truly, this shift made the literature feel more alive.

10. The Enduring Literary Legacy

The Neo-Classical Age left a legacy of clarity and structure. It taught writers how to build a solid and logical argument. Furthermore, it established the standards for modern English prose style. Consequently, we still value the precision of the early masters. Moreover, the focus on social critique remains a vital force. Thus, the age shaped the early development of the novel. In addition, the Romantic Period in Literature changed the artistic world. It gave us a new way to see nature and ourselves. Transition words summarize the impact of these two great eras. Similarly, the movement inspired the growth of the modern ego. Readers perceive the lasting power of the bold imaginative spirit. Indeed, both ages contributed to the richness of our culture. Furthermore, the tension between reason and emotion still exists today. Hence, we study these periods to understand our own minds. Truly, the dialogue between these movements defines our literary history. Finally, they provide the tools for all modern creative expression.

Eagle in House of Fame: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/05/12/eagle-house-of-fame/

For grammar lessons, visit ChatGPT to explore the platform and interact with the AI: https://chat.openai.com

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.