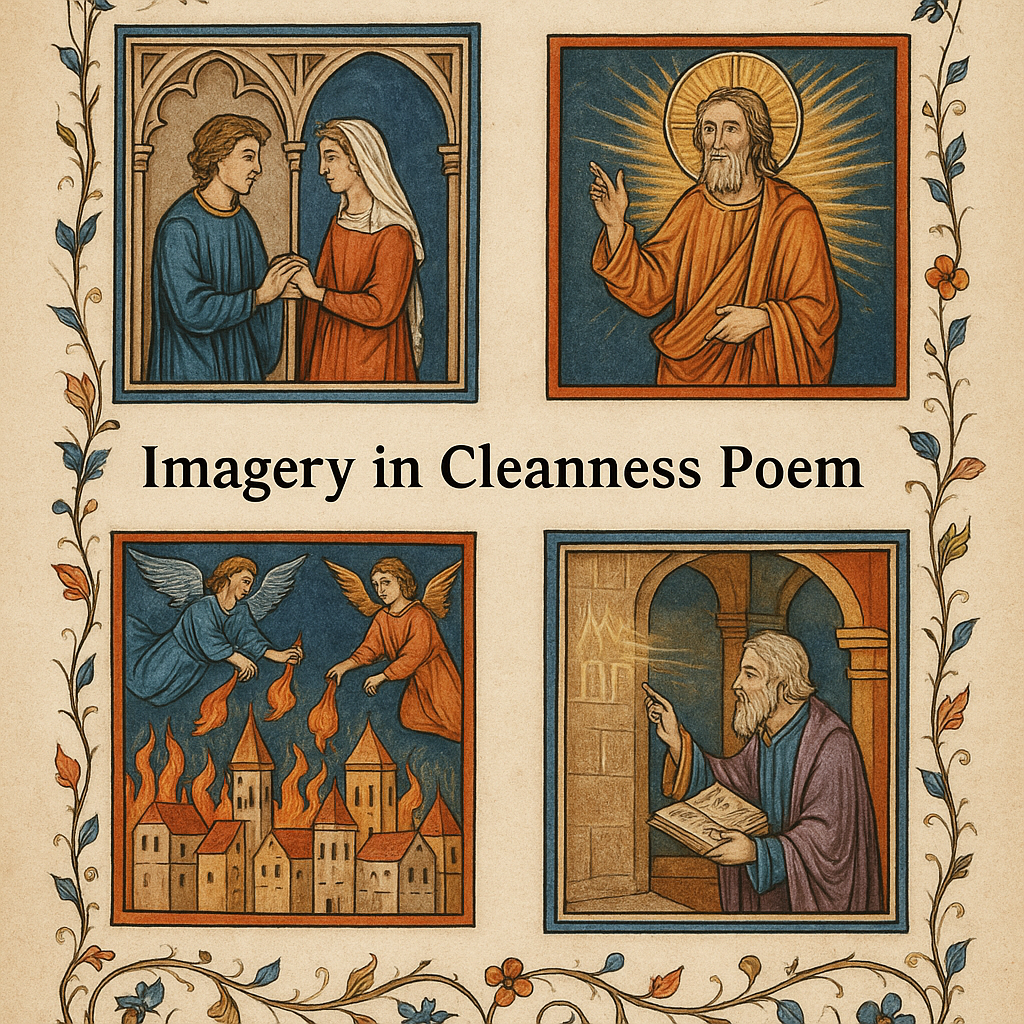

Introduction: The Power of Imagery

The imagery in Cleanness poem shapes more than description. It carries the poem’s emotional weight. Through vivid sensory detail, the Pearl Poet turns abstract theology into concrete experience. Because the poem teaches morality, imagery must strike the senses. It must feel immediate, visual, and real.

Moreover, this imagery builds intensity. It engages the reader’s emotions. Each image—whether beautiful or horrifying—adds force to the poem’s message. Through powerful language, the poet makes cleanliness and corruption unforgettable.

Imagery Rooted in Physical Sensation

The poet fills the poem with images of touch, taste, sight, and sound. These sensory experiences anchor the moral lesson. For example, when describing divine punishment, he does not speak abstractly. Instead, he shows flesh torn, fire falling, and walls collapsing. The impact is visceral.

Because readers feel the terror, they absorb the warning. Likewise, moments of purity shimmer with gentle detail—soft fabrics, sweet scents, and shining light all appear. These contrasts heighten the difference between clean and unclean.

Visual Contrast: Purity vs Corruption

One of the most striking uses of imagery in Cleanness poem lies in visual contrast. The poet constantly opposes brightness and filth, beauty and decay. For example, the wedding feast of Belshazzar is described with golden vessels, polished floors, and ornate fabrics. However, these beautiful details soon become a backdrop for sin.

The poet then contrasts this wealth with divine writing on the wall—a terrifying, supernatural message. Because of this visual clash, the moral fall becomes more dramatic. The poet turns splendor into a stage for judgment.

Natural Imagery and the Created World

Nature plays a key role in the imagery of Cleanness. The poet often turns to rivers, animals, plants, and seasons to convey mood and meaning. During Noah’s flood, the rising waters are not just punishment—they become a destructive force, washing away the impure world.

Moreover, the poet describes storms with startling intensity. Wind howls, waves rise, and animals cry out. These images do not just illustrate—they embody divine wrath. In contrast, moments of peace often use soft natural imagery—gentle rainfall, bright gardens, and still air.

Clothing and Material Imagery

Clothing imagery appears frequently and carries symbolic power. Clean garments often signal spiritual purity. Filthy or torn clothes suggest corruption. The poet describes royal robes, priestly garments, and common dress with care. These clothes reveal character.

For instance, Lot is presented as righteous, and his household’s order includes attention to clothing and cleanliness. Meanwhile, Belshazzar’s court is covered in gold and fine linen—but these external riches hide inward filth. Because clothing represents moral state, it becomes a key image throughout the poem.

Food and Feast Imagery

Feasting appears across the poem, and its imagery reveals much. Food is not just nourishment; it symbolizes spiritual condition. Clean feasts honor God. Corrupt ones provoke divine anger. For example, Noah’s sacrifice after the flood is pure, and the scent rises pleasingly to heaven.

In contrast, Belshazzar’s feast uses stolen sacred vessels. The food is rich, but the act is profane. The imagery of overflowing wine, loud music, and drunken kings becomes a moral warning. The poet uses these images to expose hidden danger in pleasure.

Light and Darkness Imagery

The contrast between light and darkness carries theological weight. Light often signals God’s presence, truth, or clarity. Darkness suggests error, chaos, or sin. The poet uses this contrast throughout the poem. For instance, moments of obedience take place in daylight. Sin often unfolds in night-like confusion.

When divine punishment strikes, it sometimes does so with blinding light. The supernatural writing in Belshazzar’s hall glows with dread. In contrast, the destruction of Sodom begins in the night, when evil thrives. These images help guide the reader’s moral vision.

Fire and Water as Dual Symbols

Fire and water serve as dual symbols in the poem. Each can cleanse or destroy. The poet uses both forces repeatedly. In Noah’s flood, water erases sin but also brings death. In Sodom, fire rains from heaven—a cleansing judgment. These elements embody divine power.

Moreover, their presence enhances emotional response. Readers feel the heat, hear the crackling, or envision rising waves. Because of their sensory depth, these images linger. They become unforgettable signs of divine justice.

Imagery of Sacred Objects

Sacred vessels, temples, and altars appear with striking clarity. These images remind readers of God’s presence. However, when misused, they trigger judgment. For example, Belshazzar drinks from holy vessels taken from the temple. This act is not only a narrative event—it is a vivid image of sacrilege.

The poet describes the vessels in glowing terms—silver, gold, shining light. Their defilement feels real and shocking. Because the image is so tangible, the lesson becomes unforgettable. Sacred things demand reverence.

Descriptions of the Human Body

The poet does not shy from physical detail. Bodies in Cleanness express inner states. The righteous appear clean, ordered, and strong. The sinful, however, suffer physical consequences. Bodies become bloated, burned, drowned, or broken.

For example, the destruction in Sodom is shown through human pain. Flesh melts, voices cry, and limbs fall. These images make the cost of sin painfully vivid. They are not abstract—they are felt.

Architectural and Urban Imagery

Cities and buildings appear often. The poet describes courts, palaces, and temples in glowing language. Yet these structures often collapse. Their destruction signals moral failure. The beauty of Sodom or Babylon cannot protect them from judgment.

Moreover, the poet lingers on these settings before they fall. This builds tension. Because their destruction is described in exact terms—walls shaking, towers falling, fire cracking—the moral failure feels structural. Corruption infects even stone.

Emotional Imagery: Fear, Awe, and Wonder

The poet captures emotional states through vivid imagery. When characters fear God, the language becomes intense. Faces pale, limbs shake, voices falter. These images communicate spiritual awe.

Likewise, moments of wonder—such as divine visions or signs—are shown with brightness, strangeness, or stillness. These scenes do not merely tell emotion; they show it. Because of this, readers feel the characters’ responses. Emotion becomes image, and image becomes lesson.

140-Word Paragraph: Belshazzar’s Feast as Imagery Showcase

Belshazzar’s feast offers a rich display of imagery in Cleanness poem. The scene begins with splendor—golden goblets, fine fabrics, and abundant wine. Laughter echoes through a lavish court. However, the poet layers this joy with foreboding. Because sacred vessels are misused, the imagery turns. The shining walls grow tense. Suddenly, a glowing hand appears. It writes on stone, and silence falls. The poet describes this moment with vivid fear—eyes widen, joints loosen, and color drains from faces. Light once symbolizing wealth now carries judgment. This shift in imagery transforms the feast into a moral reckoning. The once-beautiful scene collapses under divine weight. Through sight, sound, and fear, the poet teaches a deep lesson. Misused beauty becomes horror. Therefore, this scene embodies the poem’s core: the external world reflects spiritual truth. Imagery makes this truth visible. In Belshazzar’s fall, image and morality meet with stunning force.

Symbolic Imagery and Allegorical Meaning

Many images carry symbolic meaning. Water does not only flood—it purifies. Fire does not only burn—it cleanses. These images serve dual purposes. On one level, they describe events. On another, they suggest divine realities.

Furthermore, repetition of symbolic imagery builds connections across stories. When similar symbols appear in different contexts, the reader sees a pattern. The poet guides interpretation through repeated symbols.

Imagery as Moral Instruction

Imagery in Cleanness poem teaches. It does not exist for beauty alone. Each image pushes the moral forward. For instance, a golden object may shine, but its use defines its meaning. Used rightly, it honors God. Used wrongly, it brings wrath.

This conditional imagery teaches spiritual discernment. Readers must ask not what something looks like, but how it is used. Therefore, image becomes argument. Sensory language becomes ethics.

Conclusion: When Vision Becomes Truth

The Cleanness poem relies on imagery to bridge doctrine and experience. Without strong images, the lessons would remain abstract. However, through detailed sensory language, the poet brings his theology to life.

Because readers see, feel, and hear each moment, they understand more deeply. Purity glows. Sin burns. God speaks through storms, light, and silence. Imagery in Cleanness poem does more than paint a picture—it transforms the reader’s vision. In the end, to see the image is to feel the truth.

Structure of Cleanness Poem by the Pearl Poet: https://englishlitnotes.com/2025/07/12/structure-of-cleanness-poem/

Ishmael Reed: https://americanlit.englishlitnotes.com/ishmael-reed-american-writer/

Discover more from Naeem Ullah Butt - Mr.Blogger

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.